No More Parades discussion: random notes

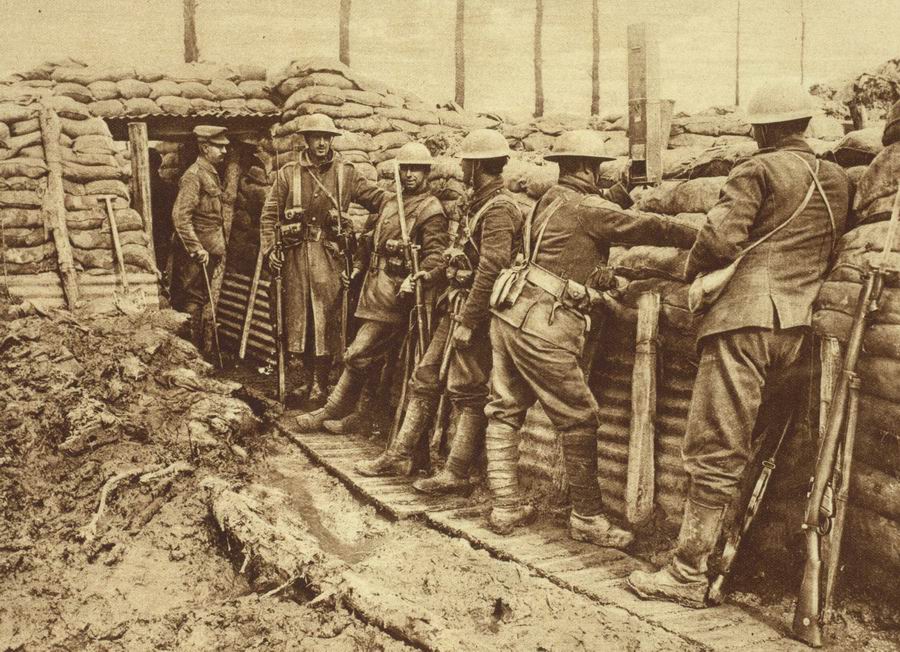

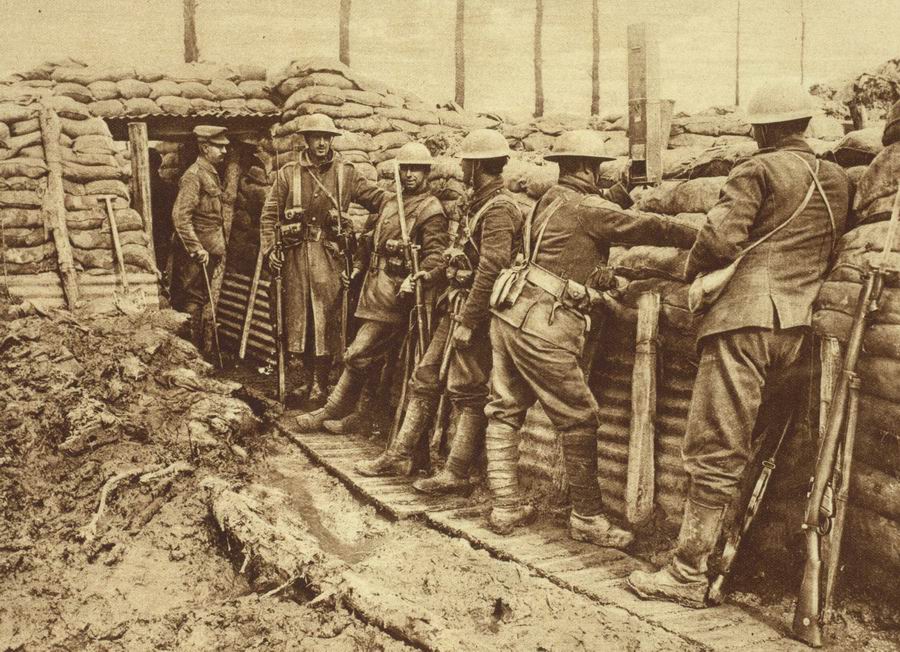

Picture source

Tietjens had walked in the sunlight down the lines, past the hut with the evergreen climbing rose, in the sunlight, thinking in an interval good humouredly about his official religion: about the Almighty as, on a colossal scale, a great English Landowner, benevolently awful, a colossal duke who never left his study and was thus invisible, but knowing all about the estate down to the last hind at the home farm and the last oak: Christ, an almost too benevolent Land-Steward, son of the Owner, knowing all about the estate down to the last child at the porter’s lodge, apt to be got round by the more detrimental tenants: the Third Person of the Trinity, the spirit of the estate, the Game as it were, as distinct from the players of the game: the atmosphere of the estate, that of the interior of Winchester Cathedral just after a Handel anthem has been finished, a perpetual Sunday, with, probably, a little cricket for the young men.

Tietjens fills the role of a great English landowner, not to England but in time of war to his regiment (and their horses). There is something Kipling-like in Tietjens’ outlook, symbolic of England’s role in the world in addition to taking care of those that fight for her. Ford paints a wonderful picture of how difficult it is to keep the men together and untangle differences. Was that meant to represent an outcome of overexpansion of the empire?

Tietjens is the perfect cog in the war machine, never questioning why something needs to be done but priding himself on being able to perform x% better than other regiments. He is aware of the political maneuvering, such as starving a leader of men in order to scapegoat him for a failed policy. He sees quartermasters getting medals for cheating soldiers out of what is theirs. The snake imagery Ford constantly uses fits more than the way the lines of men or the trenches look. The serpent-like nature of politics, personal and organizational, seems to portray war as a mirror image of society, only in a more intense context.

The tedium of war would be humorous in some other situation. During air raids and bombing, soldiers are discussing cows or their laundry business while Tietjens engages in word games. The tedium seems to affect other areas, especially the concern for winning the war. The constant refrain “Thank God for our navy” (or some variation) layers a tired confidence on top of their fatalistic outlook.

Sylvia starts out with a warrior outlook determined to win her battle with her husband, intending to “bring him to heel.” Her plans become complicated as she spends time with him and her desire for him bubbles up from underneath. Tietjens’ comment on madness (“If you let yourself go,” Tietjens said, “you may let yourself go a tidy sight farther than you want to.”) could be applied to many other feelings that are in conflict throughout the work.

Later this week I’ll try to write up a book or two I’ve read recently before continuing on to A Man Could Stand Up.