A Fringe of Blue: Australian Prelude 1893 – 1917

Related posts

I’m hoping this marks the end of the blog’s hiatus. Things have been… challenging. But I’ve really missed posting here and being part of the online book community. I thought what better way to start things off than with a couple of out-of-print books? Yeah, that’s the spirit. Evidently it’s in my blood.

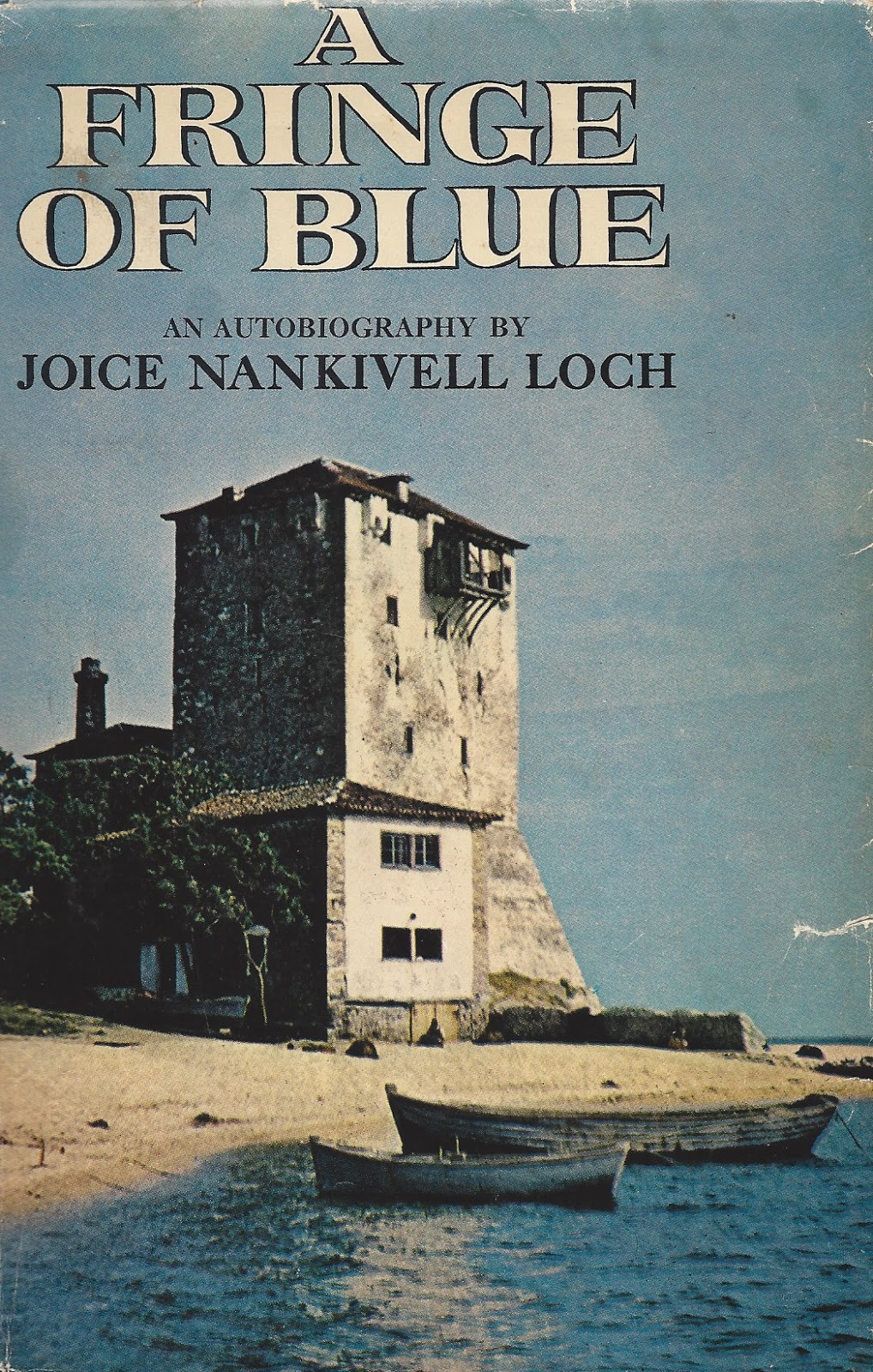

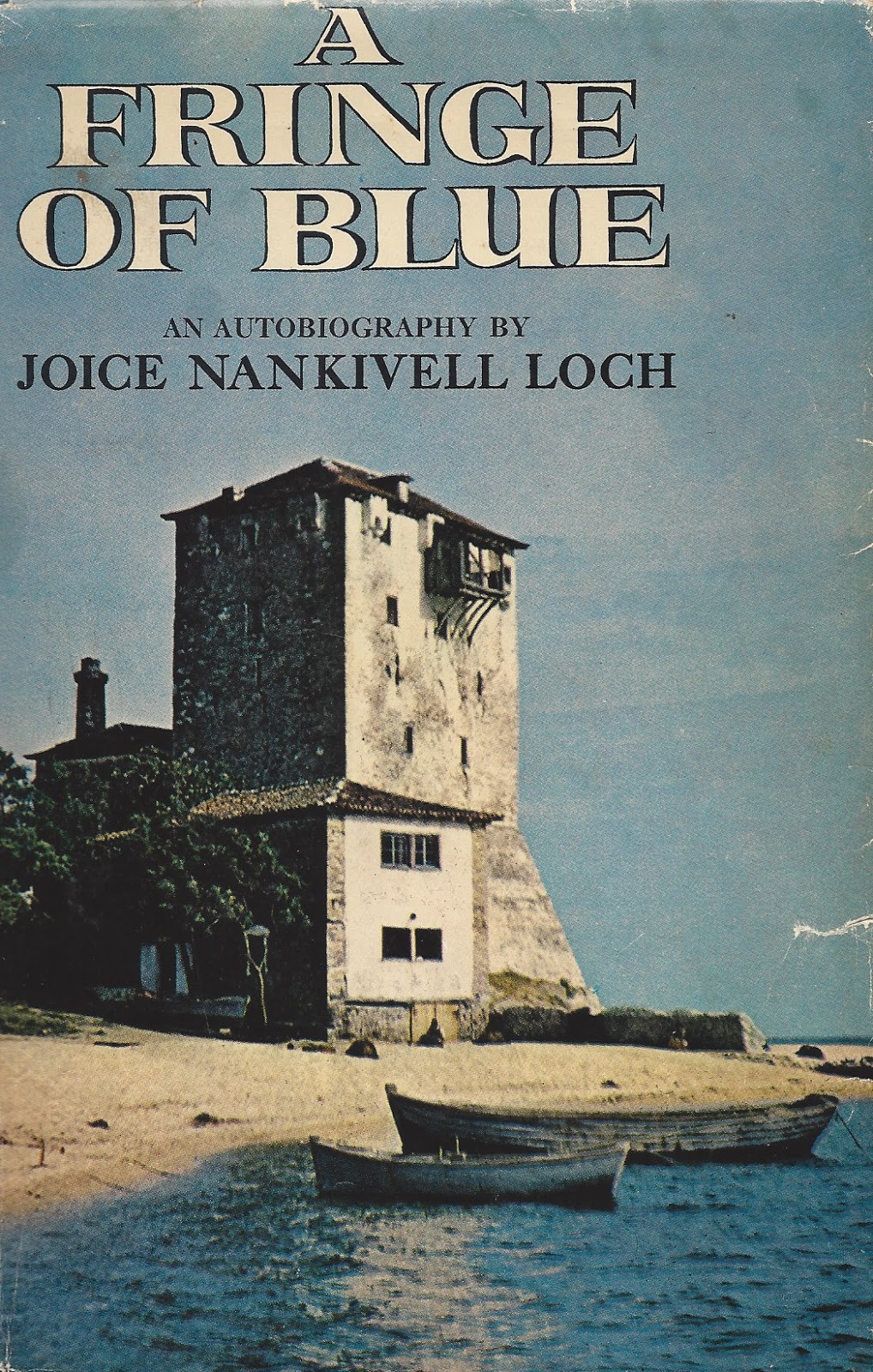

The first book is A Fringe of Blue, the autobiography of Joice Nankivell Loch. While there are several outstanding events in her life, her role in saving hundreds of Polish and Jewish children during World War II and later running a refugee camp for Poles should have kept her from being a forgotten heroine. Hopefully her exploits and the altruism of her and her husband will reach a wider audience.

The first section of her autobiography recounts Joice’s memories of growing up, mostly in Australian bush country, to her brother’s death near the end of World War I. She describes the hardships of growing up in the bush country, explaining, “Only lion-hearted women could exist on an Australian farm in those days.” (52) As she mentions several times, she thinks her mother survived simply to make sure her kids survived. Plus, her mother probably had it rougher than most women since Joice’s father repeatedly gambled on buying farms unseen (usually with help from family members), only to find them completely unworkable. Even though describing very difficult circumstances, Joice’s love of family, friends, and setting when growing up shines through. When she or her brother get into trouble, the ready-made excuse given is that they are essentially uncontrollable “bush children.”

Her family was once the wealthiest in the country with sugar-cane farms, but their wealth ended once “Blackbirding” was stopped with the passage of the White Australian Bill, abolishing the press-ganging of Kanaka laborers. Her early life expresses a fearless love of nature shared with her brother Geoff. The pair seem afraid of nothing and were always getting into scrapes, but she had no illusions regarding the dual powers of nature that she so adored: “Kill, kill, kill. All nature killing and struggling. The very rain running down immense trees drowned while it brought life.” (19) Along with her love of animals and nature was a fierce adoration of books, taking advantage of well-stocked libraries whenever she had a chance. Around the age of thirteen, Joice began her relationship with Miss Rowland, a woman who “could have inspired a log of wood to learn, and she had a knowledge of world affairs second to none, so that later when I worked in distant countries I was never much at a loss. She grounded me on a sound basis to be neighborly.” (36)

Her willingness to sympathize with and understand others shines through in her writing, as does her wit and charm. Her ability to tell a tale, whether it’s of her youthful mischief or stories she heard, such as an aboriginal tale on the origin of the platypus, makes the book a fun read. My favorite story in this section is how Australia’s capital got its name:

Mr. Macdonald, the oldest living Australian explorer in my youth, was a friend. The last of the giants. He lived with the blacks [aborigines] for years in order to study them and to compile a dictionary of the various dialects. At that time he was the only authority on the subject. …

[Discussion about the movement for deciding a federal capital]

The present site was hurriedly chosen in a final glorious weekend. It had been visited many times before. A Royal Decree was drawn up, then came a pause, until someone suggested that the place be given a name. A ‘native’ name was demanded. Why call the federal capital after a defunct statesman of another country?

“For God’s sake,” wrote one man in the press, “have a name that is truly Australian.”

A long weekend was spent on the site in quest of the name, and the oldest black, chief of a local tribe, was called in.

“What place?” he was asked. He looked puzzled and rubbed one bare foot over the other. There was much pointing to the ground, then, through the help of a local drover who knew the tribe, light dawned on him:

“Canberra,” he said.

He was asked again, and with much more confidence, for he saw everyone was delighted. He repeated: “Canberra.”

They broke a bottle of champagne over the thirsty earth and the black and they drank a lot more, shouting:

“Canberra!”

The name was added to the Royal Decree and in due course received the royal signature, and everyone was satisfied, until Mr. MacDonald pointed out that there was no such word.

A final picnic was called, and Mr. MacDonald was at it.

The oldest black with his drover friend was produced. They stood on the same hill, and pointed to the same ground:

“Canberra!” said the black.

Mr. Macdonald chuckled, the chuckle became a guffaw.

“He know no other English!” he gasped, “he means a ‘can of beer’! And really when you see the litter of bottles you can’t blame him!” If there was consternation before, there was a rout now. The name of the federal capital, proclaimed before the whole world, literally meant a can of beer. They looked bitterly at the ground which was littered with the empties of many a picnic, and went home licking their wounds. None had the courage to admit what had happened or to suggest a change of name. They felt they would be the laughing-stock of Australia. The press dropped the subject, and the incident closed—after all it is a good enough name. (46-7)

Not quite the story you normally read about the origin of the capital’s name. Joice began publishing her poetry and writing a column for a paper. She moved to Melbourne and immersed herself in the literary societies and the theater. World War One started, “[W]ith the heedless slaughter of the young of my generation. We were drenched with blood from which we were never to be clean again.” (53) The section ends with her recounting the death of her brother near the end of the war, an event where she and her mother experienced presentiments. While she doesn’t say much about Geoff’s death, she made it clear in the previous pages how close they were and how much they meant to each other. The next section, “A Fringe of Blue,” follows Joice to (among other places) England, Ireland, and Poland.