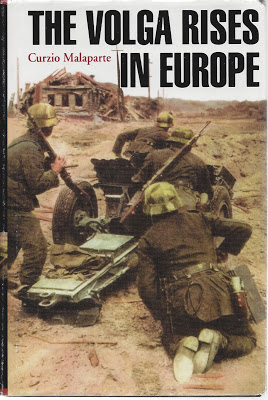

The Volga Rises in Europe by Curzio Malaparte

Translated by David Moore

Birlinn Limited: Edinburgh (1951)

ISBN 0-7394-1930-7

I enjoyed Curzio Malaparte’s novel Kaputt and his recently translated writings. When I stumbled across this collection of dispatches he wrote during World War II I grabbed it without a second thought, wanting to see some examples of his journalistic writing. This book made my list of favorite favorite 2013 reads that are out of print. (Yeah, I’m just now getting around to a write-up on it.)

During the summer of 1941 Malaparte was a front-line correspondent (supposedly the only one) following the Germans into the Soviet Union through the Ukraine front. By September 1941 he was expelled at the Germans’ request and spent four months under house arrest in Italy. Malaparte was released to cover events in Finland and starting in March 1942 he was allowed to tag along with Finnish troops during the siege of Leningrad, where he stayed for almost a year. In his dispatches from these two fronts, Malaparte writes in a style and with tropes that readers of Kaputt will recognize. His stated desire in his writing is to uncover deeper significance in moral, social, and political forces shaping the conflict.

Malaparte adds a Forward, written about a decade later, that provides some information on what he hoped to accomplish, with some notes of triumphalism:

I record these facts not out of vanity but in order to emphasize what the Anglo-American press itself freely admitted at the time—namely, that the only objective writing on the German war against Russia came from an Italian and that, unlike the British and American correspondents, citizens of free, democratic countries, I did not undertake to describe events of which I had no first-hand knowledge, nor did I stoop to make propaganda in favour of one side or the other. Apart from the fact that I was the only front-line war-correspondent in the whole of the U.S.S.R., and hence the only one in a position to see how matters really stood, I should mention that my long-standing acquaintance with Soviet Russia and her problems helped me greatly to asses the significance of events and to foresee the inevitable course of their development. (11)

Malaparte’s dispatches support his claim that he recognized there was a large social and political component of the war. He examines German, Finnish, and Soviet troops, analyzing what made them tenacious and effective while investigating and highlighting major differences. Because of these additional components, Malaparte notes in his dispatches that he believes this wouldn’t be an ordinary war and therefore would need a different type of observer, one he would try be. Some of his dispatches were censored, but fortunately the excised passages have been restored here. A note on Malaparte—he seems to have worn his Italian uniform while at both fronts and revels in the curiosity it generates and the novelty of it. This is type of writer the reader has to deal with over the course of these articles.

For anyone acquainted with Kaputt, there are moments in the first dispatch, “The Crows of Galatz,” you will find familiar in style and substance:

- ”The imminent war is perceived as a storm that is about to break, as something independent of man’s will, almost as a fact of nature.”(21)

- ”The funereal birds caw sadly from the rooftops. … All of a sudden something falls from the sky on to the pavement, right into the midst of the crowd of pedestrians. No one stops, no one looks round. I walk over to the object and inspect it. It is a piece of rotting flesh, which a crow has dropped from its beak.”(25)

As Malaparte crosses into the Ukraine with the Germans, he respects their work ethic and the way they approach the technical aspects of their tasks, as if they viewed war as just another job:

They reveal the same indifference to everything that is unconnected with their work. It occurs to me that perhaps the peculiarly technical character of this war is leaving its mark on the combatants. Rather than soldiers intent on fighting they look like artisans at work, like mechanics busying themselves about a complex, delicate machine. They bend over a machine-gun and press the trigger, they manipulate the gleaming breech-plug of a field-gun, they grasp the double handle of an anti-aircraft weapon with the same delicate gaucherie, or rather with the same rude dexterity as they reveal when they tighten a nut, or when, with the palm of the hand, or merely with two fingers, they control the vibrations of a cylinder, the play of a larte screw, the pressure of a valve. They climb on to the turrets of their tanks as if they were clambering up the iron ladder of a turbine, a dynamo, or a boiler. Yes, indeed—they look more like artisans at work than soldiers at war. (33)

Malaparte admires the Germans “streamlined efficiency” in their attitude and work, imbuing their actions with a belief that the is watching an “expression of a humanity no longer founded on sentiment alone, but on a moral principle rooted in technology.” (49) Consistent with the work-like approach of this war he notes that death took on the aspects of an industrial accident, where machines are expendable but human life was to be protected by a scientific method of waging war. He was impressed with the constant move forward into Soviet territory, but he recognized early on that advancement did not guarantee victory.

Malaparte was clearly enamored with the Soviet troops he saw although most of that contact came from his experience in Russia before the war and the Soviet prisoners he saw. He often remarks on the fundamental changes in the countryside from an agricultural basis to an industrial society, which he believes is reflected in their organization and fighting. While noting that the Soviets will not be easy enemies to subdue, he also notes the inferiority of their equipment. The Germans note that the Soviet troops were the best soldiers they had encountered to date, especially admiring their calm tenacity. There are plenty of other dynamics at work on the Soviet side, starting with the political aspect: “The fact that the Russian troops are accompanied by numerous political agents reflects the Soviet Government’s preoccupation with the necessity of exercising a political control over the conduct of the war and of spreading propaganda urging the peasant to resort to “agricultural sabotage” as a weapon against the invaders.” (95)

The politics are also reflected in what is left behind during the Soviet retreat, such as the collection of records including a 24-record set of Stalin’s speech at the proclamation of the 1936 Soviet Constitution. As the Germans move through the villages, Malaparte notes a generational gap in the Soviets. Anyone younger than 30 only had experience with the Communist government while older peasants remembered how things had been before World War I and the civil war. This gap has practical applications as reflected in the moving dispatch “God Returns to his House,” where elderly peasants in a village celebrate the retreat of the Soviets by restoring a former church, used for the past twenty years as a barn, to its former purpose and glory. At the end of the day, though, their work has been overturned by a German officer when he orders the building to be used as a stable.

When the German troops reach the Dniester River, they encounter the Stalin Line of fortifications. It’s at this point Malaparte notes that a different face of the war begins, turning from a war of machines and returning to “an old-fashioned war of infantry battalions, of gun-batteries drawn by horses.” (84) It’s at the siege of Leningrad, where Malaparte embeds with the Finnish troops around the city, that he really sees a valid comparison with World War I (which he fought in). I’m going to provide a lengthy excerpt to give a better feel of Malaparte’s ability to turn possibly boring, technical aspects into a compelling (and sometimes overly melodramatic) comparison:

But the thing that gives this familiar scene of trench-warfare a singular importance, an extraordinarily new and unexpected meaning, is the background against which it is set. No longer, as in the other war, is it a background of rugged, broken hills, of trees reduced to skeletons by gunfire, of shell-torn plains traversed in all directions by a maze of trenches, of ruined houses, standing alone amid meadows and bare fields littered with steel helmets, smashed rifles, haversacks, machine-gun belts: the usual dreary, miserable scene which opened up behind the trenches on every front in the first World War. This, by contrast, is a background of factories, houses, and suburban streets, a background which, viewed through the telescope, assumes the likeness of a gigantic wall of white glass-and-concrete façades, the likeness of an immense barrier—it is the plain buried beneath a carpet of snow that suggests the image—an immense barrier of ice that blocks the horizon. Ahead of us, forming a backcloth to this battlefield, is one of the largest and most populous cities in the world, one of the greatest of modern metropolises. It is a scene in which the essential elements are not those created by nature—fields, woods, meadows, rivers, lakes—but those created by men: the high grey walls of the workers’ houses, pierced by innumerable windows, the factory-chimneys, the bare, rectilinear blocks of glass and concrete, the iron bridges, the colossal cranes of the steelworks, the bells of the gasometers, the gigantic trapezoidal frames of the high-tension electric pylons: a scene which seems to reflect, with the precision of an X-ray photograph, the true nature, the essential, secret nature, of this war, in all its technical, industrial, and social aspects, in all its modern significance of a war of machines, of a technical and social war: an austere scene, smooth and compact as a wall, as the boundary-wall of an immense factory. (188-9)

[Reflecting on the people in Leningrad] Of all the peoples of Europe the Russian people is the one that accepts privation and hunger with most indifference, it is the people that dies most readily. This is not stoicism. It is something else—something deeper, perhaps, something mysterious. And the story that many tell of five million starving men and women, already a prey to despair, already ripe for revolt, of five million human beings cursing and blaspheming in a dark, frozen desert of houses without heat, without water, without light, without bread, is merely a myth, a ghastly myth. The reality is perhaps even harsher. Informers, prisoners and deserters are at one in describing the siege of Leningrad as a silent, stubborn agony, a slow, grey death. (The people die in their thousands every day, from hunger, privation, and disease.) The secret of this huge city’s resistance consists not so much in the number and quality of its weapons, not so much in the courage of its soldiers, as in its incredible capacity for suffering. Behind its steel-and-concrete defences Leningrad endures its martyrdom amid the ceaseless braying of the wireless loudspeakers which from the corner of every street din words of fire, words of steel, into the ears of those five million silent, stubborn, dying men and women. (192)

The bombardment of a city is not even remotely comparable, in its terrible effects, to that of a line of trenches. Although the houses consist of dead, inert matter, the bombardment seems to imbue them with a violent life, with a formidable vitality. The roar of the explosions, within the walls of the houses and mansions, in the streets and the deserted squares, echoes like a hoarse, continuous, terrifying scream. One has the impression that the houses themselves are screaming with terror, dancing up and down and writing amid the flames, before finally collapsing in a heap of blazing ruins. (222)

Malaparte delves into the political aspects of Leningrad and how it has historically been more revolutionary than other areas of the country. The tie between 1917 and this war becomes symbolic with the flying of the red flag of the cruiser Aurora above the Admiralty building, the same flag hoisted above the Palace fo the Tsars during the revolution. Malaparte sees such attitudes and events as a return of the “proletariat of Leningrad (which from the Marxist viewpoint is the most advanced and the most intransigent in the whole of the U.S.S.R.) to the Communistic spirit, as well as to the tactics of the civil war.” (198) Malaparte demonstrates an idealized vision of Soviet Communism and its advances in his dispatches, although he does acknowledge the tendency to waste time on political arguing about theory while seemingly indifferent to shortages, agony, and death.

Like he did in the first half of the book with the Germans, Malaparte examines the Finnish work ethic and why he believes them to be superior in what is needed for war, while noting that victory is not guaranteed because of these comparative edges. It is during the siege of Leningrad section that the reader will find many intersections with parts of Kaputt and The Bird that Swallowed its Cage. The story The Traitor from the latter work (and linked in my review) makes its appearance here as an aside. Stories about Lake Ladoga, especially the “Horses” section of Kaputt, find echoes in his dispatches from this front, especially his description of the area where soldiers had fallen and ended up under the ice of the lake. During the spring thaw the bodies were washed away but the “masks” or impressions of their faces in the remaining ice provides a haunting image (or embellishment).

It’s during Malaparte’s final dispatch from the Leningrad front that he notes that something has withered and died in the soul of the city as it moves from part of the then-current age to the margins of strife. It’s difficult to tell how much of this is real and how much is disillusionment on Malaparte’s part. He notes he can’t be a mere spectator, but that seems to be consistent with his style elsewhere. That’s part of what makes reading Malaparte fun for me…even when he promises he’s telling the truth it’s difficult to fully accept the claim. These dispatches show off the best parts of his style, especially when focusing on the human aspect of the war while showing the connection to political, economic, and social dimensions.

Highly recommended, although I’d recommend reading some of his other works to see if you like them before searching for this book.

LMR

How envious I am! This book isn't even available in Italian through amazon.it! I so want to read it, it seems to make a perfect companion to Kaputt and The Skin.

Dwight

The good news is that used copies in English can be had for around $5. I haven't read The Skin yet, but it definitely is a good companion to Kaputt. Like I mentioned, you'll see some intersections and what was probably some of the inspiration for several of the more fantastical stories.

Max Cairnduff

I do plan to read Malaparte, but some of his others first (as you recommend).

This – “expression of a humanity no longer founded on sentiment alone, but on a moral principle rooted in technology.” – seemed an almost Futurist sentiment.

Dwight

Good point Max. I guess such an outlook wasn't an accident given futurism's strong roots in Italy.