Ferdydurke by Witold Gombrowicz: they’re NOT a bunch of harmless duffers

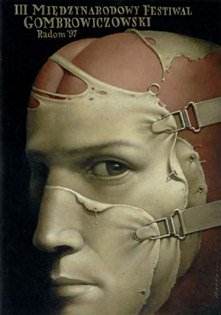

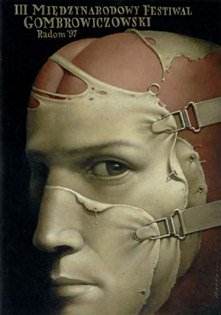

Wiesław Walkuski’s poster for the third Gombrowicz Festival in Radom, Poland, 1997

Picture source

The absurdity of the students’ actions is surpassed by the incompetence of the teaching staff. Joey’s initially sees the faculty in the staff lounge:

In the large room teachers sat at a table drinking tea and muching on breadrolls. Never before had I seen a gathering of so many, so hopeless little old men. … “These are the soundest brains in the capital,” replied the principal, “but not one of them has a single through of his own in his head; if one of them should spawn a thought, I’d be sure to chase away either the thought or the thinker. They’re actually a bunch of harmless duffers, they teach only what’s in their worksheets, and, no, they don’t entertain a single thought of their own.”

(pages 36-37)

Joey witnesses the teachers’ incompetence during his classes. “A great poet! Remember that, it’s important! And why do we love him? Because he was a great poet.” And “Great poetry must be admired because it is great and because it is poetry, and so we admire it.” (pages 42 and 43) Throughout the novel Gombrowicz makes fun of institutions and culture as well as those that submit themselves their incompetence. Breaking the cycle, though, would prove difficult since, in the students’ case, “everyone was a prisoner of his own ghastly face, and even though they should have run they couldn’t, because they no longer were what they should have been. To run meant not only running from school but, first and foremost, running from oneself…”. (pages 46-47) The outcome is predictable, for the teachers as well as the students:

Having totally lost touch with life and with reality, mangled by all kinds of factions, trends, and currents, constantly subjected to pedagogy, surrounded by falsehood, they gave vent to their own falsehood! … Their pathos was artificial, their lyricism was odious, they were dreadful in the sentimentalism, inept in their irony, jest, and wit, pretentious in their flights of fancy, repulsive in their failures. And so their world turned. Turned and proliferated. Treated with artifice, how else could they be but artificial?

(page 49)

The school section ends with a contest involving making faces, finishing in a heap of bodies as the innocent student Syphon (suck up?) has murderous words, figuratively and literally, whispered in his ear by the corrupting Kneadus. Pimko appears at the door to take Joey to his lodgings at the Youngblood residence. The family, especially the mother, takes pride in their modern approach to morals while doing away with old ways. Just as the students’ behavior was trapped in their rebellion, so are the mother’s beliefs restricted, not freeing, because of her “liberalizing” rules. The modernizing ways include a reversal of family roles as the father feminizes himself. Complicating Joey’s life is the Youngblood’s sixteen-year old daughter—the mother uses her modernist views to vicariously live through her daughter, ignoring the damage it does to the girl. Making matters worse for Joey is his belief that he is in love with the girl (Zuta)—sex and lust creep into his self-declarations. Joey reads admirers’ letters sent to Zuta and believes he has cracked the code in their horrible poetry:

The Poem

Horizons burst like flasks

a green blotch swells high in the clouds

I move back to the shadow of the pine—

and there:

with greedy gulps I drink

my diurnal springtimeMy Translation

Calves of legs, calves, calves

Calves of legs, calves, calves, calves

Calves of legs, calves, calves, calves, calves—

The calf of my leg:

the calf of my leg, calf, calf,

calves, calves, calves.

(page 161)

Projection isn’t limited to movie theaters. Throughout the torture of his “love,” Joey constantly expresses his powerlessness and worthlessness: “I was neither this nor that, I was nothing”. (page 190) Joey concocts a plan to ruin the Youngbloods as revenge for his rejection as well as everything else they put him through. This section ends in another heap of bodies as Joey and Kneadus escape to search for an ideal country lad. After being attacked by villagers who bark and bite like dogs (peasant life is getting off to a rough start), the boys are taken by Aunt Huerlecka to their country estate. The people and their actions are as unreal here as in the other sections, where servants take servitude to a higher (lower?) level while masters preserve patrician customs. The aunt’s family seems just as captive and constrained as the servants—years of custom dictated how the two groups interact. Joey’s uncle is unable to comprehend Kneadus’ infatuation with the lower class: “The worldly country squire proved childishly naïve when faced with naiveté.” (page 241) The gentry’s view echoes that of the teachers, treating the ignorant and immature peasants like children. Joey’s despair boils over at the unreality he has seen in his experiences. His lament as he and Kneadus attempt to abduct a servant emphasizes the absurdity of the expected course as well as the unexpected one:

How do we find ourselves on these tortuous and abnormal roads? Normality is a tightrope-walker above the abyss of abnormality. How much potential madness is contained in the everyday order of things—you never know when and how the course of events will lead you to kidnap a farmhand and take to the fields. It’s Zosia [Joey’s cousin] that I should be kidnapping. If anyone, it should be Zosia, kidnapping Zosia from a country manor would be the normal and correct thing to do, if anyone it was Zosia, Zosia, and not this stupid, idiotic farmhand.

page 259)

The situation at the manor spirals deeper into absurdity while Joey impotently watches everything happen (a recurring motif). As his family and their servants descend into physical violence and yet another scrum occurs, Joey runs away with Zosia, intending to dump her once he is successfully clear of the manor. His conscience gets the better of him (and his maturity?) and he appears set on carrying through on his elopement, although judging from the chapter title (“Mug on the Loose and New Entrapment”) he views this as another prison. Also swaying his decision is a kiss, a different kind of human contact from the dogpiles ending other sections. He realizes human contact is essential but it comes with a caveat: “[F]rom a human being one can only take shelter in the arms of another human being. From the pupa, however, there is absolutely no escape.” (page 281) Has the reader been had?

The absurdity of these situations leads to all sorts of contradictions. Joey, a thirty-year old who doesn’t feel grown up…who feels as if he is nothing…is turned into a teenager. He is not transported back in time to his teenage years, though. It is important that he view the world through teenage eyes at the (then) current time. At some points during his repeated kidnappings, though, he plays the role of an adult while commenting on others’ immaturity. Gombrowicz makes the difference between immaturity and innocence clear, especially when showing that immaturity dominates while innocence (Syphon) is killed. The school, the place intended to help the students mature and grow, fails to provide any meaningful education. Modern behavior proves to be another trap that limits the individual. The relationships shown in the first two sections find their basis from the master/peasant relationship shown in the final segment. Conflict turns out to be the normal way of life throughout the book, where groups only unite because of a shared fear of a third group. In a world that was fragmenting as Gombrowicz wrote Ferdydurke in the mid-1930s, the book points out the absurdity of escalating petty squabbles when bigger problems are looming.

The opening chapter shows a psychological breakdown when the adult Joey felt fragmented upon waking from his dream. This fragmentation carries throughout the story as oftentimes a person is reduced to body parts, Zuta’s calves being the most obvious I’ve described. The perverse bodily descriptions and analogies continue to represent the psychic fragmentation within. In the next post I’ll look at the book’s diversions, which goes into this topic more and provide the heart of the book.

Ferdydurke also lashes out at the “cultural aunts” he mentions in the opening chapters (see the update in the previous post on the book for additional meaning to the term). Why should he, Joey or Gombrowicz, view himself as others judge him when those judging are perverse, the natural products of the warped forms they try to impose? The forms shown in Ferdydurke, whether educational or social, focus on exterior behavior and actions which distorts the individual trying to conform to them.

“But how to describe this Ferdydurkian man? Created by form, he is created from the exterior, which means inauthentic, deformed. To be a man is to never be oneself. He is also a constant producer of form: He secretes form indefatigably, like the bee secretes honey.”

—Gombrowicz’s preface to the French edition of Pornografia, 1962 [Trans. Dubowski]

Note: all quotes and page references are to the 2000 Yale University Press edition of the novel, translation by Danuta Borchardt.

ruzzel01

Looks interesting. The face is mostly covered.

1911 compensators