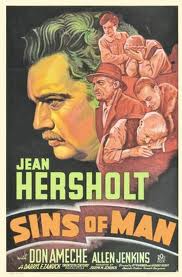

A Tale of Two Movies: Sins of Man, 1936, U.S.

Freely adapted from “Job,” the novel by Joseph Roth, “Sins of Man” is a thoroughly sentimental, painstakingly somber and devastatingly complete portrait of a man in sorrow. While it is uncompromisingly tearful, it happens also to have been splendidly performed, honestly directed and handsomely produced. In sum, a well-planned conspiracy against the lachrymal duct which has been so perfectly organized that it is impervious to any resentful cry of “You harrow me!”

Our preference, frankly, is for a more “contrasty” negative. “Sins of Man” has blocked in its tragic shadows solidly, courageously ignoring any romantic sub-plot and only in a few penultimate episodes seeking to bring its heavy theme into clearer relief through recourse to a “funny man.” Although this is a more mature approach to tragedy than the screen generally employs, and must be encouraged in principle if not in this specific instance, still there is danger in overdoing it.

– From The New York Times movie review of Sins of Man, by Frank S. Nugent, published June 19, 1936

Your Hollywood-style Job is said to be, well, exquisite. They’ve turned Mendel Singer into a Tyrolean peasant. Menuchim yodels. I simply have to see it. I will roll in the aisles on your behalf.

– From Stefan Zweig’s letter to Joseph Roth, April/May 1934

Sins of Man, “freely adapted” from Joseph Roth’s book Job, wasn’t the easiest movie for me to get a copy to watch. I lean (strongly) toward Zweig’s response. The best thing I can say about it is the movie demonstrates how horribly wrong Roth’s Job could have gone and makes me appreciate the book more than my initial lukewarm liking of it.