Apricot Jam and Other Stories—It seemed that we had been filled to overflowing, yet there was still more to come

Counterpoint, Hardcover, 375 pages

ISBN: 1582436029 / ISBN-13: 9781582436029

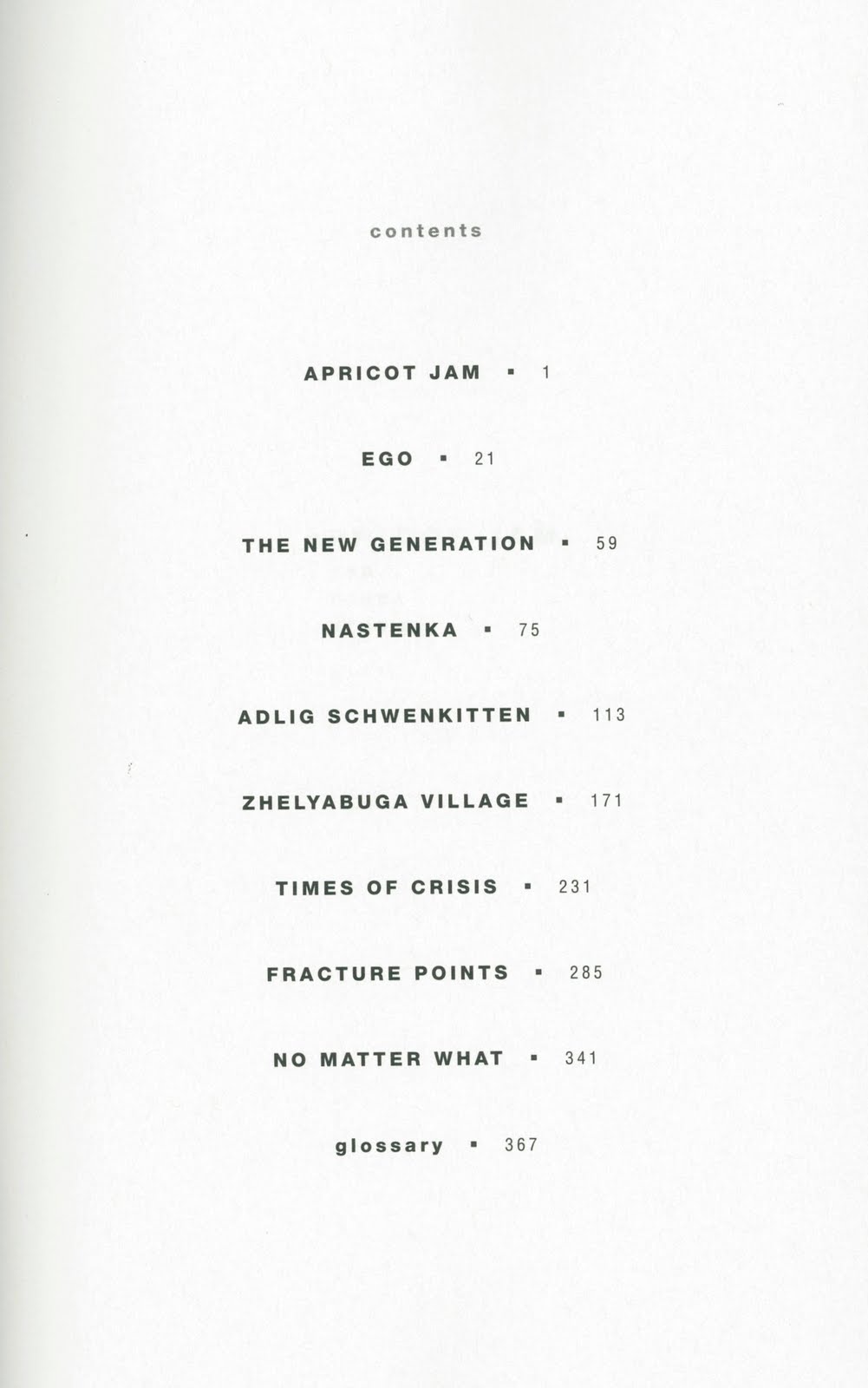

“Zhelyabuga Village” is a first person narration of an incident in a western district of the USSR during World War II. The narrator commands a sound-ranging battery setting up in a forward position in order to pinpoint German batteries. He starts by detailing the procedures, considerations, and pressures that go into such an operation. I found it fascinating to look at the technological techniques and problems that had to be addressed. As in the previous story, we see a political officer hanging around” the battery, offering nothing useful. Despite some repetitions in technicalities, I found the “war” part of this story powerful because of the no nonsense way the narrator looked after both his job and the sixty soldiers (and inadvertent civilians) under his purview. Solzhenitsyn describes an impromptu birthday party, full of fatalistic rhetoric and an elevated feeling of community. “Over this war you could have counted the number of such days on one hand. Our spirits soared. It seemed that we had been filled to overflowing, yet there was still more to come.”

The narrator skips ahead fifty-two years to describe an official visit to Oryol “for the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of Victory Day.” Characters muse about the changes in and differences of the place during the elapsed years: “It was a different world, one we had never seen before.” We meet the beauty that had been trapped in the cellar with the troops, two yellowed teeth left in her head and the hint of rape as she declares she forgets “what I need to forget.” A minor protest erupts as village women block the delegation’s caravan to protest their treatment—they gave their all in WWII and they feel ignored. After empty promises from those in charge, the old women get specific with their charges: “Never a holiday, never a day off, never a bit of leave. And what did they tell us then? Your labor will be our victory; it will help us end the war quickly and bring some peace to the country. So why have you forgotten those who toiled away, tell me that?”

“Times of Crisis” follows the life and career of Georgy Zhukov. Solzhenitsyn seems to admire Zhukov because of his love of the motherland, at least to the extent that he puts results for his country ahead of personal fame or wealth. Solzhenitsyn has shown this level of empathy with Soviet officials in other works, such as Stalin in “In the First Circle.” The first section of this story covers Zhukov’s growth and development in the Red Army fighting against separatists and bandits. The steps taken by the state against the peasants in the area take an increasingly intimidating and oppressive approach. Zhukov admires these tactics: “No great commander can manage without harsh measures.” In both sections, Solzhenitsyn seeks to understand Zhukov by imagining his inner thoughts and desires.

The second section has Zhukov writing his memoirs, looking back on his career during World War II and later. Because of his position he directly oversaw some of the USSR’s major war accomplishments, directly interacting with Stalin during many of the campaigns. Zhukov brushes aside the faults and failings of Stalin, not able to conceive that the empire’s leader could be anything other than human. Or competent. While he is adept at military matters, Zhukov flounders when it comes to political wrangling. He fails to comprehend anyone that places personal advancement over the well-being of the motherland. Shunted aside to an imposed retirement, Zhukov eventually decides to write his memoirs. The first problem he encounters revolves around presenting his experiences his relationship with other people, in particular Stalin (both ellipses in original):

It was precisely here that he saw the biggest obstacle to writing his memoirs. (Maybe he should just give up the whole thing…?) How was he, a general who had had long and close contact with Stalin during the Great War and who had seen his many moods and who had even become his closest deputy, to write about the man who was the head of government, the general secretary of the party, and soon the Supreme Commander of the armed forces? As a veteran of that war, he could scarcely believe how the Supreme Commander had since been dethroned and how a few dimwits were trying to stain his reputation by telling cock-and-bull stories—how he “commanded the front lines by looking at the globe…” (It’s true, he did have a large globe in the room next to his office, but there were also maps on the wall, and he would lay out other maps on the desk when he was working. The Supreme Commander would pace from corner to corner, smoking his pipe, and then go to the maps so as to understand clearly the report he was being given or to indicate what he wanted.) Just now they’ve thrown out the biggest windbag of them all [Meretskov], kit and caboodle. And maybe, little by little, they’ll be able to restore proper respect for the Supreme Commander. Still, some irreparable damage was done.

The second problem comes when party officials find out Zhukov is writing his memoirs, who then bring in overseers to insure his book tells the story they want told instead of what really happened. Though Brezhnev eventually approves the book, Zhukov feels empty, as if he has lost a battle because he didn’t take advantage of certain moments given to him. The book was a fight he could never win.

“Fracture Points” is an interesting look at the changes in Soviet business from World War II through the 1990s. Part one follows the rise and development of Mitya Yemtsov as he develops a successful business model that bucks the government appointed system. He grasps what is needed over the years, including the changes of the 1980s (even though “privatization” becomes a frightening word). He sees that the forced governmental interlocking parts will fail since certain sectors could not sustain their business independently. Solzhenitsyn has always been a vocal critic of unbridled capitalism, but he shows his wrath for Russians playing at democracy and capitalism without realizing all that it entails: “You rushed off to elect some self-style democrats, most of them former instructors of Marxism-Leninism, some economists, ivory-tower professors, and journalists… Who elected them?”

Part two tracks the professional career of Aleksi Tolkovyanov, a promising physics student who finds himself in the Russian army in the late 1980s just as history reaches one of its “fracture point.” The army changes him in the sense that he loses his love of science but he takes advantage of the loosened restrictions to pursue other goals. He and some friends set up a bank, providing a front for unsavory businesses. “The buy-and-sell era had already begun.” While disgusted that they have to deal with shady people, Toklovyanov hopes that the climate will change and they can restrict their business to only legitimate deals. An attempt on his life (a bomb blast in the lobby of his apartment building) destroys that hope for him. A faint light of hope persists, though, and he turns to the backer of his bank, Mitya Yemtsov. The old businessman demeans the younger generation even though they display the same sort of adaptability he did years ago. And, of course, Yemtsov intends to make a profit from their work.

Part One of “No Matter What” starts with an incident in World War II in which Lieutenant Pozushan catches members of the mess detail cooking stolen potatoes. After explaining the situation to the major, his superior admits “You cannot change human nature even under socialism,” suggesting the lieutenant allow the men to finish cooking the potatoes. The inevitability of human frailty leads to an acceptance of subversive actions.

Part Two follows a deputy-minister as he tours a section of the Angara River (probably during the 1990s) as he listens to complaints from locals about the government’s and private industries’ destruction along the river. A timber company and a series of dams spell disaster for those left along the river. Despite getting a hearing, it’s clear nothing will change: “If a decision is adopted, and even reconfirmed, there is no changing it anyway, no matter what. All will proceed according to plan.” Thus we see another thing that cannot be changed, whether it occurs under socialism or capitalism.

So how do I feel about the overall collection of stories? If I haven’t made it clear, I enjoy much about Solzhenitsyn’s writing, fiction and nonfiction, so don’t expect a completely unbiased review (even though I think he’s wrong in certain aspects of his overall framework). The strongest work in these pieces focus on life under communism. The stories on World War II appear to include personal experiences, which I found interesting but I realize such stories aren’t for everyone. Solzhenitsyn struggles in the stories (or parts of stories) set in the post-Soviet age—it’s clear he is unhappy about many things but his focus doesn’t consistently have the same bite. Which isn’t to say they aren’t good stories. It seems he was still working on how to evaluate and express his feelings on the changes in Russia, those for the good as well as for the bad. While there are no consistent themes across all the stories the feeling that a bad decision…such as missing an offered chance…lies at the heart of many unhappy or unfulfilled situations whether it be with individuals, groups, or the country. Literature, and the use/abuse of it by the Soviet system, comes in for its fair share of exposure but not to the same extent as the look at pivotal moments.

I recall seeing some announcements of this book saying this collection of stories would be a good introduction to Solzhenitsyn. If you’re looking to avoid his longer works for such an introduction, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich would be a much better choice (although I want to put in a word for the longer works, too). I have no hesitation in recommending the first four stories of this collection to the general reader looking for a sample of Solzhenitsyn general style. The remaining stories gave me various levels of enjoyment but I realize not everyone has the same interest in the writer as I do. Solzhenitsyn has some characters in the 1920s express hope for the change in the direction the country was taking, hopes we know, without having to read further, will be dashed. Fewer characters in stories set in the 1990s express similar hopes as a result of recent changes. Their path still unfolds, but Solzhenitsyn didn’t seem to think the results will be much different.

The stories employing a structure Solzhenitsyn called binary tales—two parts related by something tangible, a continuation of the same story but set years later, or simply two unrelated stories with a similar theme—can be uneven but when they click, such as the opening “Apricot Jam”, this approach adds to the story’s impact.

Just another student

Hi, I enjoyed your review of Apricot Jam. I was surprised to see so many negative reviews online, I personally enjoyed the collection very much. I think some of the stories were less crafted because they were published posthumously?

Dwight

That's probably part of the problem. Plus he was trying a new style in several of the stories and some don't have a polished feeling–that may (or may not) have changed if he had tried to publish them while alive.

I think maybe many people were expecting something different than what they read. I don't know…I enjoyed them and thought some of them extremely well done. Glad to see you enjoyed them too.

Thanks for the comment!