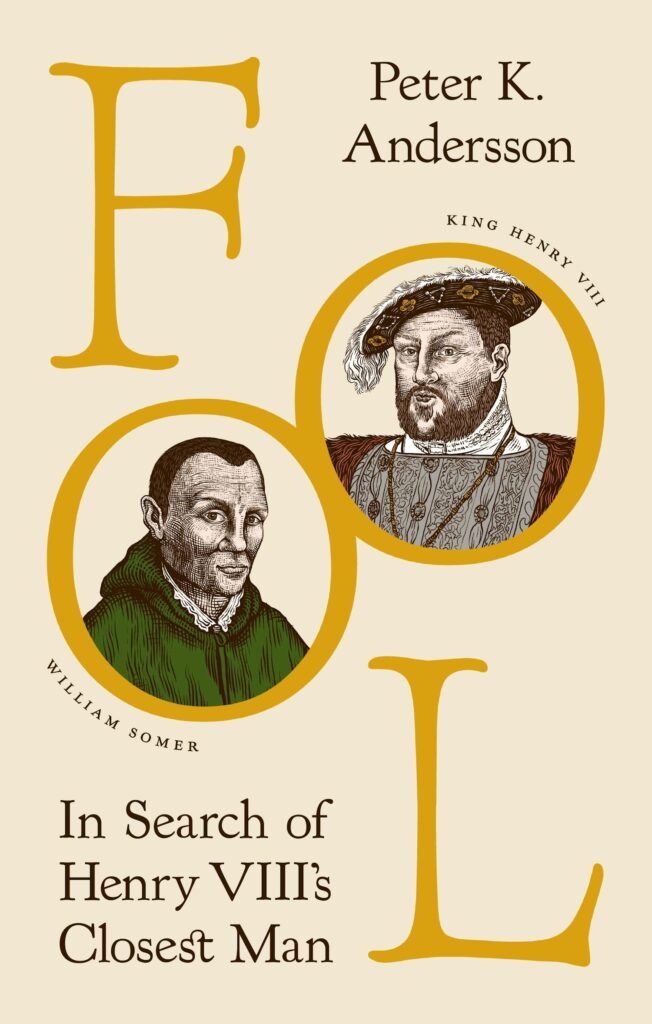

Fool by Peter K. Andersson

by Peter K. Andersson

Princeton University Press, 2023

The posthumous image of him has been entangled with the real individual, and no one has really fully tried to disentangle them. But achieving that would provide us with a unique window into both the life of the court and fundamental conceptions of humour, humanity, and deviance in the Reneissance. … Fool: In Search of Henry VIII’s Closest Man is not a conventional biography, hence its somewhat elusive subtitle. When faced with a type of source material that has been produced after a person’s death, the historian often adopts a strategy of studying representations of the person rather than the person themself, and for such an investigation there would be than adequate material in this case. … A common biography is out of the question. But what we can attempt is a study of his role and function in the social world of the royal court, which brings us closer to both the individual and perceptions of him. What type of fool was he, and what does this say about fools and early modern views of disability or deviance? What place and role did he have in the court? How did his surroundings treat and view him? How were his actions and utterances spread and quoted, and what attitude towards him does this reveal.

(pages 3, 8-9)

When speaking of Henry VIII today, his fool William Somer (one of multiple spellings) doesn’t often get a lot of attention. He makes appearances in stage plays and writings by Thomas Nashe, Samuel Rowley, and Robert Armin about 50 years after Somer’s death. Perhaps his most famous stage portrayal is his non-appearance in Henry VIII by Shakespeare and John Fletcher (staged 1613), where the audience is told in the prologue not to expect Somer in the play. (Probably because of actor Robert Armin’s retirement from acting—his portrayal of clown-type characters on stage were famous in his day.) Not everything written about Somer is extant, and what is available isn’t always reliable.

If you have read the historical fiction novel The Autobiography of Henry VIII: With Notes by His Fool, Will Somers by Margaret George then you’ve seen one portrayal of him, that as “a wry comic and sharp-eyed witness to all major events of Henry’s reign.” (Andersson’s note, where he also calls it an “insightful and well-written piece of fiction”) I have a note from page 639 of the paperback version of Autobiography where Henry calls Will a “wise commentator.”

As an aside, despite some historical inaccuracies, apocrypha, and omissions, George’s novel is a fun read. Somers (George’s spelling) plays a minor role in the novel, providing sober asides, corrections, and insights to Henry’s fictional autobiography, with the majority of Will’s notes in the novel’s introduction and closing. Back to Fool…

Andersson starts with looking at Somer’s legend and why folly was important in court life during this period (including the mythology that grew up around him afterwards), followed by a look at actual records of his place in the court and his appearance as recorded during his life. His personality and physical traits are studied, then allusions to his actual sayings in order to reveal his talent. Andersson closes by looking at Somer’s role at court (and how it relates to others) and then his legacy. Andersson notes this won’t be a conventional biography in the usual sense, but he looks at what is known, what was recorded (reliably and otherwise), and builds a plausible story for Somer’s life and role in court.

William Somer’s “name first appears in court records in 1535, when the king was in his mid-forties, and continues to crop up in documents during the rest of Henry’s reign and in those of Edward VI and Mary Tudor. William Somer is even listed as an attendant at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth in 1559. He appears next to Henry in no less than four portraits of him.” For someone so highly visible and with a posthumous reputation as a great comic figure (although some of that may be due to nostalgia of earlier days during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign), it can be frustrating to find so little original source material about the man.

Andersson looks at the dissolution of the monasteries and the impact that had on social care for people that didn’t fit into everyday life. Was Somer one of those with physical and/or mental impairment that was turned out during Henry’s religious reforms? Plausible and possible, but impossible to know. Once again we are left to conjecture if Somer was a natural fool or a talented actor (termed an artificial fool). What we do see is a history of Somer’s aggressive and sometimes violent behavior, something that became a standard trope regarding fools. In Somer’s case, though, that seems to have been true, hinting at some sort of a mental impairment. Offsetting that, though, are records of his rhyming contests with Henry, where he demonstrates impressive (and pleasing) mental dexterity as well.

Andersson provides an excellent history on fools in general, highlighting specific fools, and the depiction of such in the genre of fool literature. Piecing together Somer’s history, though, highlights the many contradictions found in his life. While he was a favorite of Henry, he was provided no accommodations and supposedly slept with the dogs. His entertainment was often solely for Henry, who also often abused him. Andersson labels Somer as Henry’s “human conversation piece.” The humor and entertainment came as much from Henry’s and other’s reactions to Somer as they were to what the fool said and did. It is a strange role for us to try and interpret today. Unlike a performer solely meant to be funny, a fool’s role was to also bear the brunt of the court’s (usually sadistic) humor while stumbling into comedy himself by apparent mistake.

In attempting to unravel the history of Somer’s life, Andersson provides great insight into several aspects of the time such as what court life under Henry as well as covering the outlook for people with disabilities then. The difficult question to resolve now, and also apparently during his time, is whether Somer was naturally a fool or an ‘artificial’ one? Andersson comes down on the side of him being a natural fool, with the occasional retort and action hinting at humor or comedy. I’m not so sure, but then again it appears it was difficult to tell during his day as well. I wonder if it possible he was simply both a natural and artificial fool depending on his mental state at the time. One of Somer’s more famous sayings was essentially a warning not to believe a thing he said, which highlights the question of who his jokes were ultimately targeting.

An interesting point Andersson makes is that Somer became a household name, but since he was a member of the court very few people would have actually have met him. This would allow for the rise in myths and rumors. His reputation would grow from these characterizations and later stage representations.

The last section of the book focuses on the legacy of Somer as well as how the role of court fool and humor in general evolved from the spontaneous and (apparently) inadvertent outburst to more sedate comedic tropes, such as the court jester or a self-aware performer. For more historical background on court fools, see Andersson’s article “The Joke’s on Who?” linked below.

Links:

- Princeton University Press’ publicity page, with the Introduction and index

- The Joke’s on Who? by Peter K. Andersson at LinkedIn

- Talking Tudors’ podcast Episode 218 – William Somer: The King’s Fool with Dr Peter K. Andersson

- A guest post by Dr. Peter K. Andersson at the many headed monster, reflecting on the challenges of trying to write a biography of Will Somer.

- Shakespeare Unlimited Episode 224 at the Folger Shakespeare Library has Andersson talking about Somer and Fool

- One last podcast, that at The History of Literature: episode 575 A History of the Fool