Hadji Murad discussion

Harold Bloom calls Hadji Murad “my personal touchstone for the sublime of prose fiction, to me the best story in the world, or at least the best that I have ever read.” Bloom argues throughout his book “that originality, in the sense of strangeness, is the quality that, more than any other, makes a work canonical.” Bloom obviously feels that Hadji Murad qualifies for originality and strangeness since “Whatever we take the canonical to be, Hadji Murad centers it in the Democratic Age.” (from Harold Bloom’s chapter “Tolstoy and Heroism” in The Western Canon) What makes Hadji Murad ironic is that, in 1896, Tolstoy published What is Art? which questions the values literature can impart. In the essay, Tolstoy takes a critical look at, among other writers, Shakespeare and the Greek tragedians. Tolstoy argued that art should promote brotherhood and Christian-like ethics, qualities he believed the cited authors did not support in their works. Yet soon after What is Art? was finished, Tolstoy began working on Hadji Murad, a blend of Shakespeare’s characterizations and Greek tragedies’ quandaries while remaining free of moralizing. I’m not as smitten with the work as Bloom but can still appreciate it for a wonderful and enjoyable example of Tolstoy’s mature work. On to the novel…

I don’t feel guilty spoiling the plot of Hadji Murad since Tolstoy reveals it in advance at almost every turn. The action covers from November 1851 to April 1852 in the Caucasus mountains and forests. For the first half of the 19th century, the Russian empire fought to conquer the Muslims in this area, achieving varying degrees of success and failure. Hadji Murad fights for the iman Shamil against the Russians until there was a falling out between the two men. Hadji Murad offers his services to the Russians, contingent upon rescuing his family from Shamil. The Russians humor Hadji Murad but have no intention of giving him command of forces or of rescuing his family. In desperation, Hadji Murad rides out from a Russian outpost in order to save his family. His actions are misinterpreted by the Russians (deservedly so after he kills his Cossack escorts), who track Hadji Murad and kill him in a fierce battle.

Similar to his best works, Tolstoy’s characters in Hadji Murad come to life in only a few lines. Even minor characters leap off the page fully formed:

At the head of the 5th Company, Butler, a tall handsome officer who had recently exchanged from the Guards, marched along in a black coat and tall cap, shouldering his sword. He was filled with a buoyant sense of the joy of living, the danger of death, a wish for action, and the consciousness of being part of an immense whole directed by a single will. This was his second time of going into action and he thought how in a moment they would be fired at, and he would not only not stoop when the shells flew overhead, or heed the whistle of the bullets, but would carry his head even more erect than before and would look round at his comrades and the soldiers with smiling eyes, and begin to talk in a perfectly calm voice about quite other matters. … War presented itself to him as consisting only in his exposing himself to danger and to possible death, thereby gaining rewards and the respect of his comrades here, as well as of his friends in Russia. Strange to say, his imagination never pictured the other aspect of war: the death and wounds of the soldiers, officers, and mountaineers. To retain his poetic conception he even unconsciously avoided looking at the dead and wounded.

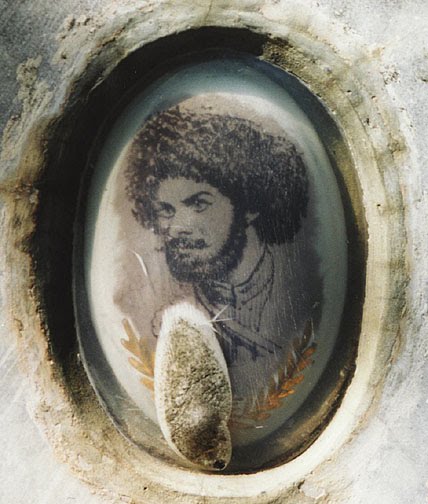

Picture source

Tolstoy’s empathy for his characters makes them that much more engaging, drawing the reader into the story. A soldier’s innocent love for his superior’s wife feels to the reader as painful as the emotions the character experiences. Throughout the work there are “doubles” within the story, providing comparison and contrast. We see this young soldier’s innocent love echoed in another soldier’s lewd behavior toward a fellow soldier’s wife.

Tolstoy can be particularly brutal with Tsar Nicholas, portraying him as a weak, ignorant and petty tyrant driven more by flattery and lust than any consideration for his country. Despite his ineptness as a leader, Nicholas can be ruthless, whether in ordering a student to be flogged enough to cause his death (despite the ban on capital punishment) or in his scorched earth policy in the Caucasus (which insures hardening his enemies). There are still some sympathetic moments, if you can classify them as such. Nicholas reaps a system that accepts no report other than success—in other words, reports bear no relationship to what happened in the field. If all you hear are flattery and success, it takes a certain level of talent to recognize and understand the true status of affairs.

As an aside, there are moments in the chapter with Nicholas that are echoed in Solzhenitsyn’s portrayal of Stalin in In the First Circle, although Stalin is presented much more sympathetically. On a further side note, look for the similarities between Murad and Nicholas, which can be unnerving. OK, enough for side notes…

Shamil, the second power opposing Hadji Murad, appears as a leader direct from Machiavelli’s The Prince, wielding cruelty and an iron fist out of necessity, not desire. Yet Tolstoy provides humor and humanness in Shamil’s situation as the iman’s youngest wife denies him her presence for the evening, inconveniencing and torturing him just as he does to others. While there is no doubt Tolstoy has disdain for the Russia under Nicholas, his contempt for Shamil’s world seems clear even if much more subtly and compassionately drawn.

Hadji Murad’s interview with Voronstov provides a foretaste of his relationship with the Russians, both men talking past each other while, on another level, they understand each other completely:

The eyes of the two men met, and expressed to each other much that could not have been put into words and that was not at all what the interpreter said. Without words they told each other the whole truth. Vorontsov’s eyes said that he did not believe a single word Hadji Murad was saying and that he knew he was and always would be an enemy to everything Russian and had surrendered only because he was obliged to. Hadji Murad understood this and yet continued to give assurances of his fidelity. His eyes said, “That old man ought to be thinking of his death and not of war, but though he is old he is cunning, and I must be careful.” Vorontsov understood this also, but nevertheless spoke to Hadji Murad in the way he considered necessary for the success of the war.

Hadji Murad understands his quandary and the hopelessness of his situation yet he remains resolute in his undertakings. He knows Shamil’s offer to return and fight for the iman is a sham, recalling the fable of a falcon that had been caught and tamed by men. Escaping captivity and desiring to live at home again, the falcon returns only to be pecked to death by the other falcons which would not allow him to stay with the marking of humans on him. “And they [Shamil’s men] would peck me to death in the same way,” thought Hadji Murad. “Shall I remain here and conquer Caucasia for the Russian Tsar and earn renown, titles, riches?” While Murad knows he could achieve that, he never wavers in attempting to rescue his family.

I wanted to provide an extended excerpt on Hadji Murad’s death because it provides a dispassionate mirror on all of his actions:

Another bullet hit Hadji Murad in the left side. He lay down in the ditch and again pulled some cotton wool out of his beshmet and plugged the wound. This wound in the side was fatal and he felt that he was dying. Memories and pictures succeeded one another with extraordinary rapidity in his imagination. Now he saw the powerful Abu Nutsal Khan, dagger in hand and holding up his severed cheek as he rushed at his foe; then he saw the weak, bloodless old Vorontsov with his cunning white face, and heard his soft voice; then he saw his son Yusuf, his wife Sofiat, and then the pale, red-bearded face of his enemy Shamil with its half-closed eyes. All these images passed through his mind without evoking any feeling within him—neither pity nor anger nor any kind of desire: everything seemed so insignificant in comparison with what was beginning, or had already begun, within him.

Yet his strong body continued the thing that he had commenced. Gathering together his last strength he rose from behind the bank, fired his pistol at a man who was just running towards him, and hit him. The man fell. Then Hadji Murad got quite out of the ditch, and limping heavily went dagger in hand straight at the foe.

Some shots cracked and he reeled and fell. Several militiamen with triumphant shrieks rushed towards the fallen body. But the body that seemed to be dead suddenly moved. First the uncovered, bleeding, shaven head rose; then the body with hands holding to the trunk of a tree. He seemed so terrible, that those who were running towards him stopped short. But suddenly a shudder passed through him, he staggered away from the tree and fell on his face, stretched out at full length like a thistle that had been mown down, and he moved no more. He did not move, but still he felt.

When Hadji Aga, who was the first to reach him, struck him on the head with a large dagger, it seemed to Hadji Murad that someone was striking him with a hammer and he could not understand who was doing it or why. That was his last consciousness of any connection with his body. He felt nothing more and his enemies kicked and hacked at what had no longer anything in common with him.

The opening and the abrupt ending center around the symbolism of a thistle, mentioned in the death scene above. If the reader misses the analogy, such as the mangling of the thistle’s flower described in terms of damage to the human body, the narrator makes it explicit:

“What vitality!” I thought. “Man has conquered everything and destroyed millions of plants, yet this one won’t submit.” And I remembered a Caucasian episode of years ago, which I had partly seen myself, partly heard of from eye-witnesses, and in part imagined.

Just as the narrator’s plucked thistle no longer looks appropriate for a bouquet, Murad’s body, void of life, no longer reflects the headlong spirit that had been contained within. Martin Price, commenting on another Tolstoy character, said “Characters like Anna are tragic figures because, for reasons that are admirable, they cannot live divided lives or survive through repression.” His description could apply just as well to Hadji Murad (whether the reasons are admirable or not).

For those interested in the historical basis of Hadji Murad, more can be found at The Russian conquest of the Caucasus By John Frederick Baddeley (1908). Baddeley’s portrait of Hadji Murad shows a much more ruthless character than in the novel, yet Tolstoy follows the warrior’s life closely in many details. The entry on Hadji Mourad in the index of Baddeley’s book provides an overview that sounds similar to Tolstoy’s story:

Hadji Mourad:

Fights against the Murids at Khounzakh, 255; kills Hamzad, 287; Is driven by intrigue to adopt Muridism, 351; made prisoner by Russians, his escape, 352; consequences of his defection, 354; wounded at Tselmess, 355; joins Shamil, 365; good service at the Minaret ford, 424; daring raids near Shoura and Djengontai, 426; fights Bariatinsky at Gherghebil, 435; is beaten by Argouteensky at Meskendjee, 436; Shamil’s most prominent lieutenant, 438; his raid on Shoura, slaugher of a Russian garrison, 439; his night raid on Bouinakh, his fame, Shamil’s jealousy, 440; condemned by Shamil he surrenders to the Russians, his captivity in Tiflis and mission to Grozny, he goes to Houkha, his devotion to wife and family, Melikoff’s narrative of his life, 441 and n.; his escape, 442; and characteristic death, 443; his head sent to St. Petersburg, Okolnitchi’s opinion of him, 443; his widow presented to Bariatinsky, 476

I found it interesting to compare Baddeley’s ending of Hadji Murad, composed independent of Tolstoy, as well as his conclusion on Murad’s life which includes a mention of the author:

“Two days later, on the 23rd of April 1852, the fugitives were discovered and surrounded in a wood by a large party of militia, who were soon joined by other troops and by the inhabitants of the district, led by a blood enemy of Hadji Mourad’s. And now took place one of those dramatic scenes so frequent in Caucasian warfare. Seeing escape to be impossible, the Murids dug a pit with their kindjals, killed their horses, made of them a rampant, and intoning their death-song, prepared to sell their lives as dearly as possible. As long as their cartridges lasted they kept their enemies, a hundred to one, at bay; then Hadji Mourad, bare-headed, sword in hand, leapt out and rushed on his death. He was cut down, and two of his men with him; the other two, sore wounded, were taken prisoners and executed. So, on the 24th April 1852, in Vorontsoff’s words, “died as he had live Hadji Mourad, desperately brave. His ambition equaled his courage, and to that there was no bound.” (pages 442-443)

It will be long, indeed, ere Hadji Mourad’s name and fame are forgotten on the mountains he defended or on the plains he ravaged; and if, as reported, Tolstoy has written a work, to be published after his death, having Hadji Mourad for hero, the world at large will one day be possessed of the Avar raider’s full-length portrait drawn by a master-hand. (page 443)

The text, translated by Louise and Aylmer Maude, is available online at The University of Adelaide and is what I used for all quotes in this post (link is dead). If you decide to take advantage of this online text, note that there is “A List of Tartar Words Used in Hadji Murad” at the very end. I recommend printing this list before beginning the novel. I also need to note that there are many misspellings, most of which can be figured out easily, but I found it distracting (and made me wonder what else was incorrect).

The Literature Network has the same translation, but I have not had a chance to review it.

This post is part of a Classics Circuit Tour – White Nights on the Neva: Imperial Russian Literature.

Stephen Pentz

If you'll forgive a side-note: "Hadji Murad" was one of Wittgenstein's favorites. (He also greatly admired Tolstoy's "The Gospel in Brief"- which Wittgenstein said changed his life, although he never professed to be a Christian.)

Wittgenstein said he liked "Hadji Murad" because, in it, Tolstoy made his points directly through the characters and the action of the story, without the comment and didacticism found in his other works. As to whether this is true or not, I defer to others who are more familiar with Tolstoy than I am.

Rebecca Reid

I'd never heard of this Tolstoy piece. Thanks for sharing, sounds quite interesting.

Dwight

I seem to live for sidnotes, so no forgiveness needed. And Wittgenstein is correct. While there is no moralizing, it is amazing how sympathetic he paints those in the Caucasus. I will have to check out "The Gospel in Brief"…I have only read sysnopses of it.

And thanks Rebecca for doing this circuit and giving me the 'excuse' I needed to finally read this!

Valerie

I learned quite a bit from reading this post — firstly, I wasn't aware of this work by Tolstoy; and also I didn't really know about this part of Russian and Muslim history. This classics circuit tour has been an interesting one!

Dwight

Valerie…glad the post proved fruitful for you. I'm new to the classics circuit but I'm sure Rebecca will be happy to hear you've benefited from it!