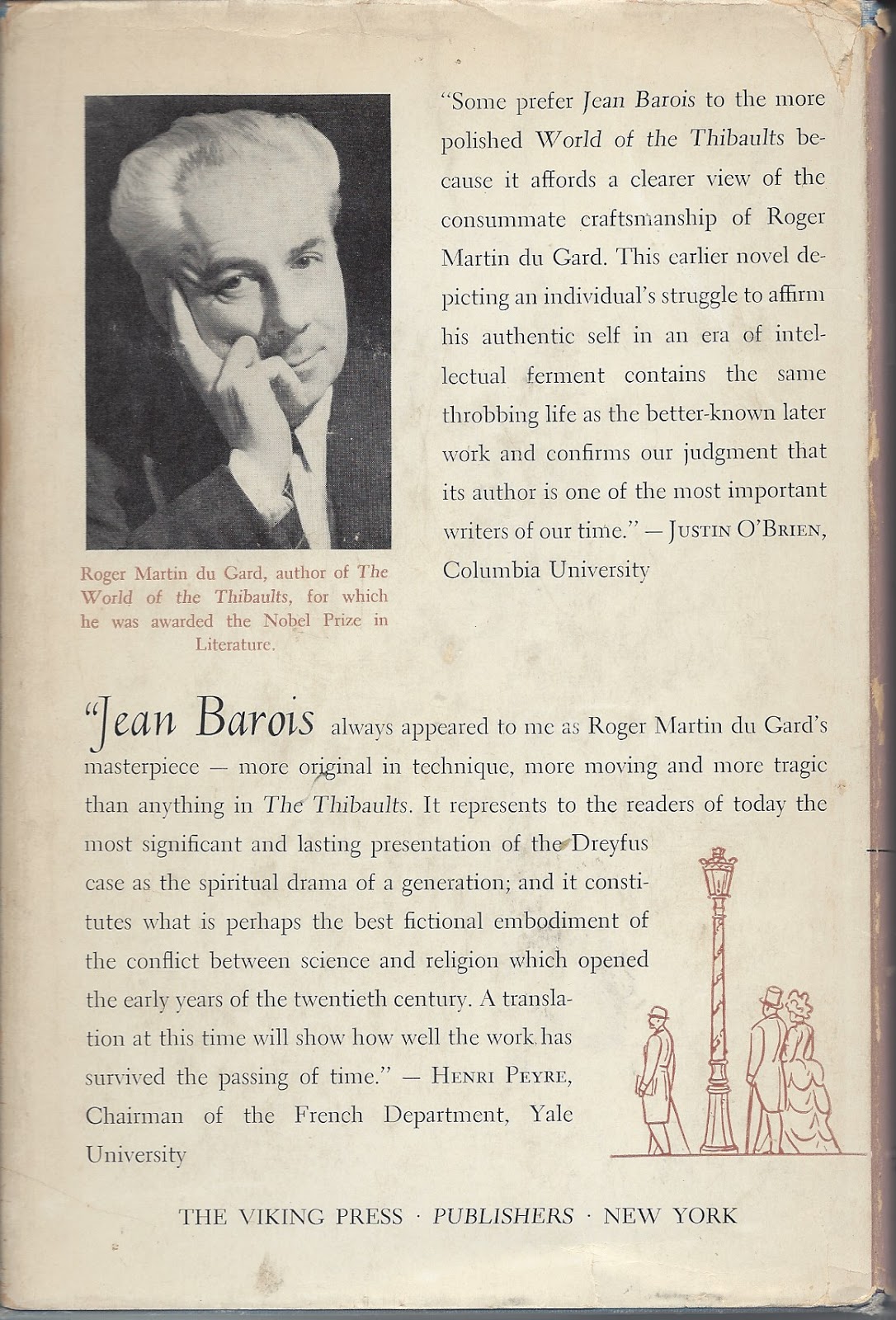

Jean Barois by Roger Martin du Gard

Translated by Stuart Gilbert

Viking Press, 1949

(original publication in 1913)

Some side notes on the novel…Martin du Gard worked on the novel from 1910-13 and turned the manuscript over to his publisher, who had promised to publish his next work. After reading the manuscript, though, that publisher balked at publishing the book, calling it a total failure. Fortunately Martin du Gard met an old schoolmate who happened to be a publisher. The manuscript was shared with André Gide, whose enthusiasm for it not only insured its publication, but also led to Martin du Gard joining the Nouvelle Revue Française.

I’ll provide an overiew of the story, but if you want more details on what unfolds I recommend checking out Bob Corbett’s book review as it’s very good.

The book is divided into three parts. Part I covers Jean’s youth, starting in 1878 when he was twelve. Jean is on the verge of death, suffering from tuberculosis, a hereditary condition in his family. He overcomes the physical infirmities only to suffer a spiritual crisis, but his discussions with his small-town abbé doesn’t satisfy his questions about the anomalies between Catholic dogma and science. Jean moves to Paris to study medicine and falls in love with the natural sciences, while discussions with a priest of a “symbolist compromise,” where a deeper truth lies beneath symbolic dogma and figurative stories, fail to edify Jean. He returns home to his father’s deathbed, appalled at the religious conversion of the dying man. The imminent fear of death causing a turn toward religion will be echoed again a couple of times later in the novel. Jean marries his childhood sweetheart, Cécile, not telling her about his religious doubts. She is a devout Catholic and his rejection of religion over the next few years horrifies her and causes their eventual split. His desire for absolute belief in science drives him to resign his post at a Catholic university (where he was upbraided for teaching evolution), leave his wife and daughter, and move to Paris alone. He revels in his freedoms, of thought and of belief, immune to the suffering he causes in his family.

Part II shows Jean and his young friends launching a periodical named The Sower (Le Semeur), which they see as championing a new morality backed by science and turning away from religion. Jean understands what they are up against in the inertia of the masses, who are not necessarily happy with their lot but resistant to change. The extended planning meeting scene includes trite comments at times, but the enthusiasm shown for their mission is palpable. They dedicate their first issue to Marc-Elie Luce, a member of the Senate and renowned philosopher. His independence appeals to the group, becoming something of a father figure to the young men (although he’s only 15 years older than Jean). Luce, delighted at the dedication and attention, cautions the group to exhibit tolerance and empathy. Jean bristles at Luce’s observation that The Sower is too aggressive:

“We’re all of us enthusiastic, convinced of the truth of our ideas and ready to fight for them. I’ve no compunction about showing a certain—intolerance.” As Luce makes no comment he continues after a moment’s pause. “I believe any young, forceful theory of life is bound to be intolerant. A conviction that starts by admitting the possible legitimacy of convictions directly opposed to it is doomed to sterility. It has no driving force, no fixity of purpose.” (136-7)

These words, or rather these ideas, will ironically come back to haunt Jean. The Sower takes off and a year after its launch (in 1896), the staff takes an interest in the Dreyfus Affair. I felt the novel really took off at this point, weaving facts and real publications into the narrative. While the focus of this section is on Jean and his reactions to the court cases surrounding the affair, knowing the outline and timeline of events will help the reader make sense of the magazine’s staff comments and the stands they take. The events of 1898 and 1899 receive the most coverage, especially the trial of Emile Zola and the retrial in Rennes, with The Sower becoming a champion against Dreyfus’ conviction. The high-water mark of the novel is also its ugliest moment: members of the staff happen to be together with Luce when they hear of the arrest of Colonel Henry, who confessed to forging documents instrumental in Dreyfus’ conviction. The news of Henry’s suicide is met with “a long, fierce cry of exultation, shrill with an almost intense glee.” (210) The delight taken by the so-called humanitarians in someone’s death reveals the cost of their narrow-minded focus and, to Luce’s earlier point, their lack of tolerance and empathy. The strange verdict after the retrial in Rennes, upholding Dreyfus’ conviction although noted with extenuating circumstances, provides a disillusioning close to the magazine’s staff’s efforts. Jean vows to continue fighting for justice, but the toll his coverage of the affair begins to show. The damage is compounded with a personal insult and loss—upon Jean’s return to Paris from the trial, he finds his lover has run off with another magazine staff member. Jean carries on, but despite his high profile and the continuing popularity of The Sower (albeit with reduced circulation from the heady days of the affair), something seems to be lacking in Jean. Part II closes after Jean has been in a serious carriage accident. Worse than the physical pain, Jean is shaken by his reaction just before the crash: he prayed. During his convalescence he writes his will, renouncing the Church and restating his convictions in favor of scientific reason. While the document lays out his beliefs in strong declarations, there is also a feeling that it is an attempt to bolster his wavering belief (or unbelief, if you will).

After the heady coverage of the Dreyfus Affair, somehow Part III avoids being anticlimactic. We see Jean, several years later, still running The Sower but its popularity has decreased as Jean has begun arguing against extremism in several high-profile events. He admits to Luce that some of his beliefs are wavering, hinting that history is not always a straight-line towards progress. There is a fallout between magazine staff members, with disillusionment setting in for many of them. My favorite scenes in this part, though, are Jean’s interaction with younger generations. He is shaken when his daughter, unseen for many years, decides to become a nun even after reading all of his writings. Young writers dismiss Jean’s new-found tolerance and claim his work to be a failure. Even worse, he is shocked by their rigid nationalism and resurgent Catholicism. In conjunction with his emotional decline, his tuberculosis resurfaces. Jean agrees to move back to the country and live with his wife, where he embraces Christianity before he dies.

Jean Barois is usually noted as capturing societal impacts during the Dreyfus Affair, and those claims are rightly made. Take how Proust used the Dreyfus Affair in In Search of Lost Time to show the internal composition of his characters as well as society in general and turn it up a couple of notches…that will give you an idea of Martin du Gard’s specific use of the crisis to illustrate the development of Jean. The novel is more than just a reflection on the affair, also capturing the religious and intellectual questions of the time.

A quick word about the writing style…the novel uses written documents (letters, articles, etc.) in addition to dialogue-heavy scenes. The latter read very much like scenes in a play, with a brief introduction that feels like staging directions, then quickly moving to the action/dialogue. I found it to be a very effective combination that moved the story along and allowed jumps in time to feel natural (or at least not feel unnatural).

There are many interesting characters in addition to Jean and his family, but Marc-Elie Luce figures as my favorite. Even though Jean’s generation looks up to Luce, few of them follow his example of tolerance and none of them follow his personal route of marriage and a large family. Luce’s family seems to give him a courage or resolve as he faces death with the same principles and in the same manner as he lived. Those of the younger group facing death betray their claimed tenets in their final moments.

The translation into English was done by Stuart Gilbert, who also translated all of The Thibaults. Gilbert has a solid reputation for his translations of French works to English, although there were a couple of things that bothered me, mostly minor details. For example, I cringed every time a French character said “old chap” (from grand ami and other phrases). More major, though, was calling the figurine that Jean has on his mantle Michelangelo’s “Slave.” Which slave? Granted, Martin du Gard’s original ‘title’ isn’t much better, but from the description of the piece I’d guess it to be the Rebellious Salve. I could be wrong, so I’ll appreciate input from anyone with more knowledge on this. I harp on the figure because it proves to be an important symbol during key moments in the novel.

The combination of studying the crisis of faith during this modernist period with the various faultlines within society exposed by the Dreyfus Affair worked to the novel’s advantage, highlighting the problems of both. A nice addition to literature covering fin de siècle Europe. Highly recommended.

Some of my writing on the background of the novel and a few of its themes benefited from David L. Schalk’s excellent book Roger Martin du Gard: The Novelist and History, Cornell University Press, 1967. Parts of this post may have inadvertently paraphrased Schalk’s chapter on Jean Barois, mainly because his summary and discussion lay out the subject matter so well that it’s hard not to internalize it. Schalk mentions two themes/devices in which he didn’t go into much detail, but I’ll mention them in case you read the novel—they are helpful things worth looking for. There is a “love-death identification” or association, such as when Jean and Cécile “make the first gestures of love” while waiting for Jean’s father to die. The second interesting point I wanted to highlight is Schalk’s mention that Martin du Gard calls the main character “Jean” in Part I and the final chapter and “Barois” in between (“during his active life”). Schalk ascribes this return at the end to his first name as giving “a sign of his [Martin du Gard’s] deep pity and sympathy.” I don’t disagree with that, but I think there is more going on, such as highlighting the state of mind to which Jean has returned. Schalk also goes into detail on how time flows in the novel—with precision in the first two parts, then with occasional vagueness in the last part. He also includes a perceptive quote from Dennis Boak about Jean’s outcome: “Barois is never able to escape his environment and heredity, and thus his end in the Church he has fought is, paradoxically enough, itself an illustration of [scientific] determinism.” For anyone wanting to read Martin du Gard’s work, I highly recommend Schalk’s book.

Fred

Excellent review. Sounds interesting. I've never read anything by du Gard.

Dwight

I had not either and was very interested in The Thibaults to compare with other works around World War I. Sadly I think the only work of his in English translation currently published is Lieutenant-Colonel de Maumort, an unfinished work. Fortunately Jean Barois is easily available used in the $4 – $6 range.