Lawless Republic: The Rise of Cicero and the Decline of Rome by Josiah Osgood

Basic Books, 2025

This book tells the story of Cicero and his rise to prominence as a trial lawyer, from his debut in the courts in the late 80s BC to his death nearly four decades later. Cicero’s successful defense of many influential men accused of murder, extortion, and other crimes earned him wealth, favors to call in, and a name for himself, which he parlayed into a career in politics. … Cicero’s career is a mirror to this age, so this book is about not only his most famous cases but also the larger struggle between law and violence. …

At the heart of Cicero’s story lies a strange irony: the career of Rome’s greatest trial lawyer also demonstrates how the rule of law broke down. To an extent, Cicero was directly implicated in the Republic’s problems. As a politician who held high office, he bore responsibility for failing to address social inequality. As a lawyer, he sometimes advanced arguments for disregarding the law. But more often, Cicero’s legal and political career illustrate problems that went beyond him, which any democratic society may find itself struggling with. How, after an outbreak of violence, do you restore the rule of law? How do you protect against the threat of domestic terrorism without suppressing civil liberties? How do you hold to account those who incite violence? When should voters decide a politician’s fate, and when should jurors? Cicero’s own extraordinary story and the tumultuous years he lived through provide no simple solutions to those hard questions. But they do help to show what holds up the rule of law, what threatens it, and what happens when law gives way to disorder. (from the Introduction, emphasis mine)

Josiah Osgood’s previous book, Uncommon Wrath: How Caesar and Cato’s Deadly Rivalry Destroyed the Roman Republic, highlighted two key contributors to Rome’s move from republic to empire. In this book he adds Marcus Tullius Cicero as another key contributor, both personally and as a reflection of the breakdown in the Roman judiciary system and rule of law during this time.

Cicero, born in 106 BC, came of age during the lead-up to and the actual civil war of Sulla in 83-2 BC. Attempts to reform government and the law courts at the end of Sulla’s dictatorship were passed with varying success. Cicero’s first appearance in a law court in 80 BC would have happened during this attempt to restore normalcy.

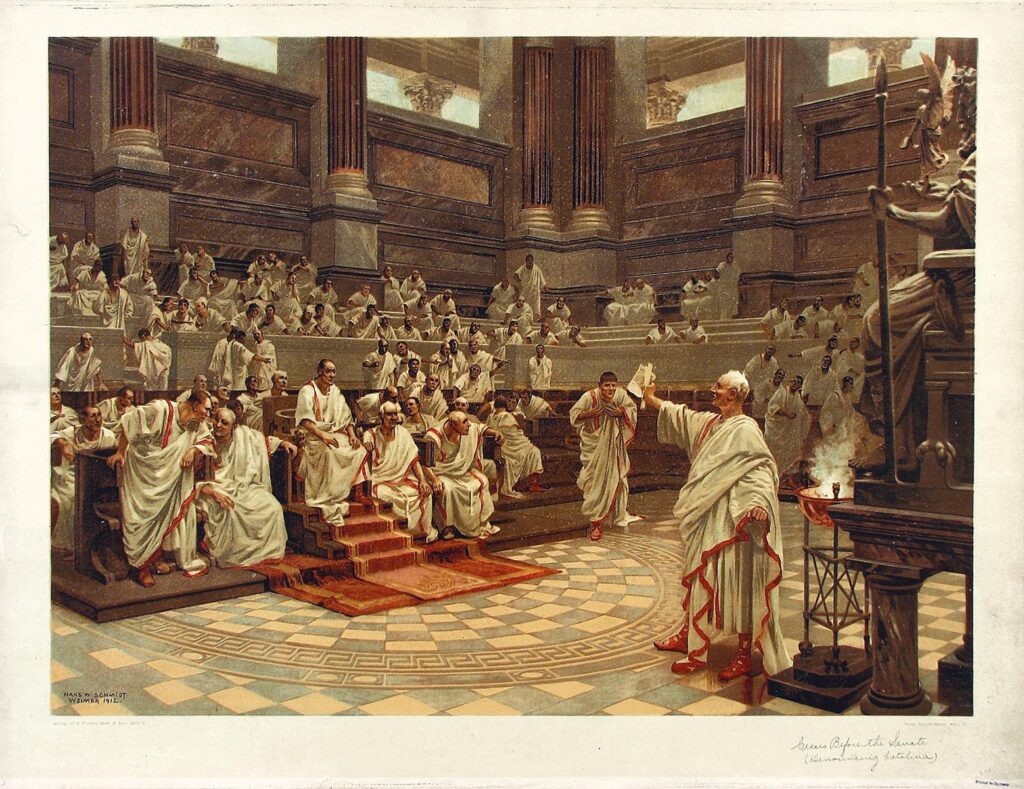

Osgood focuses a large part of the book on the trials Cicero argued during the course of his career, covering his relations with the leading powers of the day (whether formal leaders or influencers) and how the government was changing in these uncertain times. Cicero’s political history is covered, with emphasis on his role as consul during the time of the Catiline conspiracy/attempted coup. Cicero’s role and attitude in the execution without trial of the suspected conspirators is unflinchingly relayed, as is his conduct in his legal defense of a Roman man named Milo accused of a political murder: “The laws are silent amid weaponry.”

In other words, violence rules when legal systems break down. Cicero’s part in that erosion of trust in the legal system is at the heart of this book. You’ll notice the title doesn’t necessarily make Cicero the reason for the decline of Rome, but his role in certain trials and as consul hastened its demise by maintaining that under certain circumstances the state of nature takes over for what is allowed. One question (to me) that arises in reading this is how much of a ‘victim’ of the societal decay was Cicero amid his contribution to that decline. Sulla had destroyed all the rules, then tried to put them back into place. Once ignored (and unpunished) though, how binding were the new laws going to be? And what was it going to take to consistently apply them?

The book follows some of the criminal trials that Cicero defended or prosecuted, all of which reveal problems with the Roman legal system. Changes were constantly being made to address some of the system’s deficiencies, but there always seemed to be ways around the solutions implemented. You see a greedy governor stealing artwork, then buying off jurors despite laws in place to supposedly address such problems. Rival factions end up in court, hoping to settle legally what they failed to achieve through force. And once Cicero decided to run for political office, how successful can he reconcile the potential conflicts of interest with his legal stances? It seems clear that Cicero, in part, took on (mostly successful) legal defenses of men in power in order to add to his own political power.

In their pursuit of their own ambitions, Roman politicians were increasingly ignoring customary and legal restraints on power such as limited commands, regular elections, and a prohibition on reaching for weapons when passions flared. Cicero himself…showed a willingness to disregard laws when he thought them unjust or inconvenient. Perhaps there are times when one needs to obey a higher law than the laws of men. But as the escalating rancor and violence in Rome shows, there is a grave danger to civil society when that attitude becomes common. Cicero had helped to bring on forces that would ultimately kill him and destroy the Republic. (page 279)

Cicero’s fall is well known following the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC. Initially following Pompey in the senators’ flight from Rome, he became a noted apologist for the assassins. His attempt to ‘save’ the republic at this point was like trying to resurrect something already dead. It didn’t have to be dead, but the actions taken on both sides to ‘save’ the republic seemed to hasten its end. Cicero began to see some of the philosophy he had applied in his career as a defender being used to excuse post-assassination manipulations of the law. Also, being in the spotlight again after being politically and literally exiled would have fed his ego and the gratifying thrill of being an influence on public affairs again.

Despite his reconciliation with some of the post-assassination leaders as they jockeyed for power, he continually backed the wrong side or was discarded by those that saw him only as a temporary useful ally. The application of the rule of law had deteriorated so much during his career that to try and call for it at this point was fruitless. Or as Osgood puts it, “without law, there is no limit on revenge.”

For a long time, Cicero’s speeches were studied so that speakers could use his rhetorical techniques and practices to their benefit. While not a biography, Osgood’s study looks at the setting behind these speeches and why Cicero framed his discourses the way he did, as well as what were some of their repercussions and influence on unfolding events. The book also provides great insight into how the Roman law courts worked (and often didn’t) during this period. There are potential parallels with today that Osgood evokes for readers to mull over, but as noted in the opening quote there are no easy answers for such hard questions.

While reading this book I often thought of Mike Duncan’s book The Storm Before the Storm: The Beginning of the End of the Roman Republic which puts the breakdown of the Roman republic (or maybe the set-up for it’s fall) in the events of the 50-100 year span before the actual change into empire. It started before the coverage in this book but also includes some of what happened during Cicero’s adult life that laid the groundwork for the fall. I see (inexplicably) that I have not posted on that book, so I hope to track down my notes on it and post about it soon.

More:

- Josiah Osgood on Cicero and the Fall of Rome at the Daily Stoic Podcast

- I was unfamiliar with this podcast but watched the episode and quite liked it. At the start the Catiline conspiracy is the focus and Osgood highlights the difficulty in evaluating Cicero at this point. His rhetoric and lofty speech in calling out the plot (maybe his ‘finest hour’ to use the comparison made in the podcast) has to be separated from his actions afterwards. Also highlighted is how Cicero had to live with the precedents he set and their fallout. Something I didn’t realize before watching was that Osgood had translated part of Sallust’s history about the Catiline conspiracy (stay tuned for more on that). I was impressed by how deep they went into principles versus pragmatism and how it applied to Cicero, which complicates the lingering question on how to exactly view him. They mention the great Seneca quote that Cicero praised his own achievements, not without reason but without end. One of the key takeaways is how complicated Cicero was, making any evaluation of him much harder.

- Josiah Osgood on Caesar and Cato’s Epic Rivalry: Episode 82 at Stoa (Stoic Meditation). Covers the topic of Osgood’s previous book

- A few books on Cicero I’m familiar with if you want to dig deeper (and there are many more out there):

- Cicero and his Friends: A Study of Roman Society in the Time of Caesar by Gaston Boissier (text at the link)

- Cicero: Politics and Persuasion in Ancient Rome by Kathryn Tempest (link is to the Bloomsbury Publishing reprint in 2014; first published in 2011 by Continuum International Publishing Group)

- Cicero: A Portrait by Elizabeth Rawson (Also available in several publication versions—Osgood calls this a well rounded look at Cicero, combining Roman politics, philosophy, and social history. I’ve added it to my to be read list.)

- I need to revisit the HBO series Rome. What I remember in it of Cicero was that he reminded me of a Mr. Bean-type of character, going which way sentiments blew on what to do (which might not be that far from what Osgood and others present him doing during the period covered in the series, finding which pragmatic parts fit his principles). Maybe I’m remembering the characterization wrong.