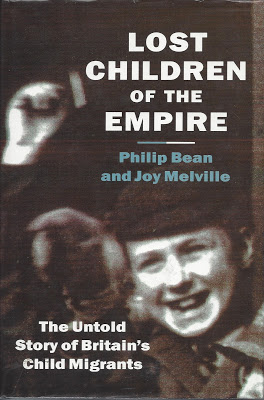

Lost Children of the Empire: The Untold Story of Britain’s Child Migrants by Philip Bean and Joy Melville

The Untold Story of Britain’s Child Migrants

Unwin Hyman Limited (London); 1989

ISBN: 0-04-440358-5

In 1618, a group of orphaned and destitute children left Britain for Richmond, Virginia in the United States. It was the start of an extraordinary era in British history, formally referred to as Britain’s child migration scheme—a more acceptable phrase than child exportation—and was to last almost 350 years. The final boatload left only some twenty years ago, in 1967, when ninety children left Southhampton for Australia, but altogether about 150,000 children were “exported” to outposts of the British Empire—to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and, to a lesser extent, South Africa, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and the Caribbean. (page 1)

Lost Children of the Empire is a remarkable overview of Britain’s child migration scheme, where orphans, “street kids,” and other children were packed off to colonial destinations, all with government assistance or blessing. Philip Bean and Joy Melville did a great job of presenting details of the different phases of the migrations along with excerpts from letters/writings from the exiles. Reading their letters, occasionally detailing abuse but more often ill-treatment and hardship, can be heartbreaking at times. Quite a few, though, show a resilience that always amazes me about the human spirit.

There were several distinct phases in child migration. The earliest started when the Virginia Company in America requested local officials to provide “unwanted children” to help fill in for a shortage of labor. In the next century, “child migration was bound up with a different policy: the transportation of convicted felons, mostly to the colonies.” Common law breakers as young as seven were transported as well as “potential trouble-makers.” In the early 19th century, emigration was seen for many as a relief valve for too many children and the substantial increase in juvenile offenses.

Starting around 1849, philanthropic organizations began to form specifically to handle child migration, with most of the children going to Canada. The circumstances for many of the children is that they weren’t adequately being taken care of at home, were embarrassments to families (such as out-of-wedlock children), or were seen as potential problems. Only a third were genuine orphans, despite the habitual use of “orphan children” used by these organizations. The attitude at the time was that a pure, ennobling life in the countryside and wide-open spaces would cleanse the moral degeneracy and pollution of these young souls. Not to mention these schemes provided stock to far-flung parts of the British Empire. Having the “right kind” of stock, though, seems to depend on the curative assumptions about the countryside.

So what kind of life did the children find upon arrival in their new homes? Whether living at a group home or placed with a family, it seemed to be the luck of the draw. Some of the supporting philanthropists appear to have had good hearts and good intentions, but that’s not enough when it comes to insuring a child’s safety and well being. Many of the letters from former emigrants make it clear that a substantial number of families where the children were placed viewed their wards as slave labor. Incentives, such as having the children work for their board until they were fourteen (at which point they had to be paid), insured that many children would be returned to a group home to be replaced with younger help. Staff at the group homes and families where the children were placed were rarely interviewed or examined, so all sorts of abuse is detailed in the migrant’s words.

There was a government inquiry into child migration headed up by a civil servant, Andrew Doyle. His report, published early in 1875, was damning when comparing the claims versus the reality he found. The point that kept appearing in his report was the question of whether or not the children were really better off by being sent abroad. Even if some were, what about the many who weren’t? He pointed out the lack of inspections on the families with whom children were placed and almost no follow up on how the children were doing. His call for elemental safeguards, though, ended up being undermined by those that had the most at stake in the enterprise—the philanthropists. Most of the benefactors were Protestant, so Doyle’s Catholicism was attacked and his report dismissed as religious pandering. A few of his recommendations were instituted, but usually because they benefited the government or philanthropists. While some of the philanthropists had good intentions, Bean and Melville make it clear that the migrations was a profitable enterprise for them, too.

Around 1890, though, hostility toward the child migrants increased in Canada. The stigma of being unwanted was constantly used against the Home children, especially as jobs became scarce for locals. A few provinces passed laws regulating immigration. The number of immigrants declined for a few years, then began to rise again until World War I. Once a law was passed limiting immigrants to older than 14 years of age (contradicting all earlier arguments that the younger a child was sent, the better), the supposed last group of young children were sent from Britain to Canada in 1925. But that wouldn’t stop the children from being sent abroad in the name of Empire building.

Nevertheless, for all these countries, it was open house on British children. The British government, always eager to save costs at home at the expense of colonial governments abroad, cheered on the children. The voluntary societies collected the subsidies and, under no constraints whatsoever, made their decisions about the type of regime under which the children should be brought up.

Few curbs were placed on them and there was not a hint of a code of good practice. There were no objective arrangements to inspect the children’s progress; to check on their happiness; to give them access to personal and family records; to arrange for them to be sent home if they could not settle and had a parent or parents in Britain; to educate them well enough to get a professional job; to provide after-care.

The children boarding the emigration ships were often cheered off by classmates at the boat. Listening to an account of what happened to one child in Australia many years later, a horrified teacher said, “Oh, my God, if only we’d known. There we all were, waving and thinking that they were all going off to this better world.”

That, too, is what the children thought. (page 92)

Children began to be sent to institutions called farm schools in Australia in 1913, Canada in 1935, and Rhodesia in 1946. It is noted, though, that one of the more famous farms on Vancouver Island did not produce a single farmer despite intentions. Once World War II was over, the return of London evacuee children caused a short-term evaluation of the effects of separation from families, but it wasn’t long before child migrants began being sent around the empire again. As Bean and Melville wryly put it, “The same old arguments for sending the children were brought out, the same mistakes were still made.” The main child migrant agencies shipped off 10,000 British children to Australia after the war.

The history of child migration in Australia is in many ways a history of cruelty, lies and deceit. For instance, children were told that their parents were dead; that they came from deprived backgrounds; that they had been “rescued” and should be grateful. … Yet these children were not orphans. And most of the families they came from were not poor or deprived. Marriage breakdown and illegitimacy rose sharply during and after the Second World War and unwanted children were often place in children’s Homes in the understanding that they would be fostered or adopted. This belief stopped the parent(s) and other family members from enquiring about the children. …

Children who were sent to Australia with brothers and sisters were also promised they would all be kept together. Yet often they were split up on arrival and either never saw their brothers and sisters again, or too rarely to have a normal brother and sister relationship. … The policy of the agencies was to cut children off from their previous life, in order to make it “easier” for them to adjust to their new country. (pages 111-112)

Since the relocation to Australia was more recent and efforts have been somewhat successful in locating families, there are plenty of reports from this wave of emigrants. The comments from the (now) adults are surprisingly compassionate regarding their parents. There is still a common theme of cruelty in the orphanages, farms schools, or other institutions. Very few of the children sent to Australia were adopted or fostered, but a common theme around acceptance of their situation (since they didn’t know any better at the time) is repeated over and over. You can almost see them coming to terms with what happened as they tell their stories and reassess what really happened. Many chose to blank out these experiences. Some of the stories recount a sadistic cruelty that is almost unbelievable. One ex-Christian Brother who served at Bindoon (made famous in Oranges and Sunshine…see below) wrote to three children he had saved from drowning at the institute’s swimming hole, apologizing for saving them. “He admitted that, looking back, it might have been a blessing if the creek had claimed them, in view of what a terrible life many ultimately led, ‘suicides, alcohol, broken marriages, loneliness, desertions—a life of misery.’” Another description used for one place is “brutalizing cruelty,” providing cruelty disguised as discipline.

There is a chapter titled “The Children’s Voices,” where letters and interviews from migrants willing to talk about their experience are printed. As the authors note, many are in tears when retelling these stories, and many are hesitant to speak openly about what happened to them. It’s a powerful section. “[C]hildren in that day and age were not considered to be quite human, but rather some sort of creature to be whipped into shape as they matured.” Not all the child emigrants speak badly about their situations. Many of the provided quotes from the boys sent to Rhodesia were positive in parts or in whole. And some of the migrant children did receive an education, although school seems to be an afterthought most of the time.

One message coming up over and over again is the children’s lack of identity. The children, once grown, were constantly lied to or given the run around when trying to find out about their family in Britain. Records were routinely suppressed. Original families were also constantly lied to. Many parents were shocked to find out their children had gone abroad. They thought they had been adopted or placed with a foster family nearby. Many of the children didn’t even know their correct name or birthdate, making an investigation of their family history even harder. “The child migrants’ increasingly desperate and failed attempts to find out information about themselves and their families led to the remarkable history of the Child Migrants Trust.” This was led by social worker Margaret Humphreys, and the story is told in the book and movie Oranges and Sunshine (see “Related books” below). So few people knew that children were still being sent to Australia until the late 1960s that one man was compulsorily detained in a UK psych ward for his claims of being shipped to Australia as a child.

In all the time of the migration, no one seemed to care about the children’s legal rights. Many were emotionally scarred, unable to form relationships throughout their lives. As one of the concluding statements notes, “Child migration was meant to be in the best interests of the child. But throughout its history, the children never came first.” And earlier: “What is so extraordinary about the child migration scheme is that at no time were any legal safeguards made governing the welfare of the many thousands of child migrants sent out by the voluntary societies.”

Overall, I thought Bean and Melville did a remarkable job of remaining as even-handed as possible in their reporting, which is why I’m choosing to post on this book. They do make pronouncements and judgments, but often such conclusions come through in their word choice more than actually stating them. Considering the length of time the child migration scheme(s) was in effect, I thought they did an extraordinary job of organizing and presenting the material. The book is out of print, but copies can be found at book sellers online for not a lot of money (particularly the hardcover version). Very highly recommended.

Related books:

- New Lives for Old: The Story of Britain’s Home Children by Janet Sacks and Robert Kershaw is another great overview of the entire Home Children programs.

- Oranges and Sunshine (originally titled Empty Cradles) by Margaret Humphreys concentrates on the children sent to Australia. Made into an excellent 2010 movie, also titled Oranges and Sunshine, starring Emily Watson. I thought the movie was so well done I compiled an extensive list of quotes from it.

- The Little Immigrants: The Orphans Who Came to Canada by Kenneth Bagnell focuses on the Canadian migrants. It is estimated that 11% of Canada’s population is descended from these child migrants.

- The Home Children by Phyllis Harrison consists of letters written by Home Children in Canada about their experiences about their journeys to Canada, life in the homes, and their lives since then.

- Joy Weare has an impressive number of pictures related to the Australian migrants on her “Oranges and Sunshine” Pinterest page.

There are several more books, documentaries, and movies I know about, but have not read or seen. I can highly recommend all of the above if you are interested in exploring more on this topic. The Wikipedia page on Home Children contains many more. There is also an extensive bibliography and list of reports and papers at the back of Lost Children of the Empire.

If you have read any book on this topic or seen any related video movie/documentary, please feel free to talk about it in the Comments and add links if you have posted on any of them.

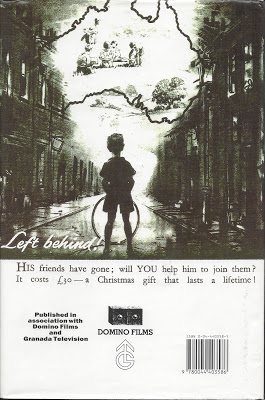

In the 1950s, a poster from the Fairbridge Society showed a slum child in Britain gazing at an outline of Australia in the sky. His loneliness could, it seems, only be relieved by emigration. The plea for funds comes next: “Help him join his friends,” is the message. (page 38)

Actual text on the back cover: “Left behind! His friends have gone; will YOU help him to join them? It costs £30—a Christmas gift that lasts a lifetime!”

I don’t think they realized how ironic that statement could be.