No More Parades discussion

The one thing that stood out sharply in Tietjens’ mind when at last, with a stiff glass of rum punch, his, officer’s pocket-book complete with pencil because he had to draft before eleven a report as to the desirability of giving his unit special lectures on the causes of the war, and a cheap French novel on a camp chair beside him, he sat in his fleabag with six army blankets over him–the one thing that stood out as sharply as Staff tabs was that that ass Levin was rather pathetic. His unnailed bootsoles very much cramping his action on the frozen hillside, he had alternately hobbled a step or two, and, reduced to inaction, had grabbed at Tietjens’ elbow, while he brought out breathlessly puzzled sentences…

There resulted a singular mosaic of extraordinary, bright-coloured and melodramatic statements, for Levin, who first hobbled down the hill with Tietjens and then hobbled back up, clinging to his arm, brought out monstrosities of news about Sylvia’s activities, without any sequence, and indeed without any apparent aim except for the great affection he had for Tietjens himself…All sorts or singular things seemed to have been going on round him in the vague zone, outside all this engrossed and dust-coloured world–in the vague zone that held…Oh, the civilian population, tea-parties short of butter!…

And as Tietjens, seated on his hams, his knees up, pulled the soft woolliness of his flea-bag under his chin and damned the paraffin heater for letting out a new and singular stink, it seemed to him that this affair was like coming back after two months and trying to get the hang of battalion orders…

…

So, on that black hillside, going and returning, what stuck out for Tietjens was that Levin had been taught by the general to consider that he, Tietjens, was an extraordinarily violent chap who would certainly knock Levin down when he told him that his wife was at the camp gates; that Levin considered himself to be the descendant of an ancient Quaker family…(Tietjens had said Good God! at that); that the mysterious ‘rows’ to which in his fear Levin had been continually referring had been successive letters from Sylvia to the harried general…and that Sylvia had accused him, Tietjens, of stealing two pairs of her best sheets…There was a great deal more. But having faced what he considered to be the worst of the situation, Tietjens set himself coolly to recapitulate every aspect of his separation from his wife. He had meant to face every aspect, not that merely social one upon which, hitherto, he had automatically imagined their disunion to rest. For, as he saw it, English people of good position consider that the basis of all marital unions or disunions is the maxim: No scenes. Obviously for the sake of the servants–who are the same thing as the public. No scenes, then, for the sake of the public. And indeed, with him, the instinct for privacy–as to his relationships, his passions, or even as to his most unimportant motives–was as strong as the instinct of life itself. He would, literally, rather be dead than an open book.

And, until that afternoon, he had imagined that his wife, too, would rather be dead than have her affairs canvassed by the other ranks…But that assumption had to be gone over. Revised…Of course he might say she had gone mad. But, if he said she had gone mad he would have to revise a great deal of their relationships, so it would be as broad as it was long…

The doctor’s batman, from the other end of the hut, said: “Poor–O Nine Morgan…” in a sing-song, mocking voice…They might talk till half-past three.

But that was troublesome to a gentleman seeking to recapture what exactly were his relations with his wife.

Before the doctor’s batman had interrupted him by speaking startlingly of O Nine Morgan, Tietjens had got as far as what follows with his recapitulation: The lady, Mrs Tietjens, was certainly without mitigation a whore; he himself equally certainly and without qualification had been physically faithful to the lady and their marriage tie. In law, then, he was absolutely in the right of it. But that fact had less weight than a cobweb. For after the last of her high-handed divagations from fidelity he had accorded to the lady the shelter of his roof and of his name. She had lived for years beside him, apparently on terms of hatred and miscomprehension. But certainly in conditions of chastity. Then, during the tenuous and lugubrious small hours, before his coming out there again to France, she had given evidence of a madly vindictive passion for his person. A physical passion at any rate.

Well, those were times of mad, fugitive emotions. But even in the calmest times a man could not expect to have a woman live with him as the mistress of his house and mother of his heir without establishing some sort of claim upon him. They hadn’t slept together. But was it not possible that a constant measuring together of your minds was as proper to give you a proprietary right as the measuring together of the limb? It was perfectly possible. Well then…

What, in the eyes of God, severed a union?…Certainly he had imagined–until that very afternoon–that their union had been cut, as the tendon of Achilles is cut in a hamstringing, by Sylvia’s clear voice, outside his house, saying in the dawn to a cabman, “Paddington!”…He tried to go with extreme care through every detail of their last interview in his still nearly dark drawing-room at the other end of which she had seemed a mere white phosphorescence…

They had, then, parted for good on that day. He was going out to France; she into retreat in a convent near Birkenhead–to which place you go from Paddington. Well then, that was one parting. That, surely, set him free for the girl!

He took a sip from the glass of rum and water on the canvas chair beside him. It was tepid and therefore beastly. He had ordered the batman to bring it him hot, strong and sweet, because he had been certain of an incipient cold. He had refrained from drinking it because he had remembered that he was to think cold-bloodedly of Sylvia, and he made a practice of never touching alcohol when about to engage in protracted reflection. That had always been his theory: it had been immensely and empirically strengthened by his warlike experience. On the Somme, in the summer, when stand-to had been at four in the morning, you would come out of your dug-out and survey, with a complete outfit of pessimistic thoughts, a dim, grey, repulsive landscape over a dull and much too thin parapet. There would be repellent posts, altogether too fragile entanglements of barbed wire, broken wheels, detritus, coils of mist over the positions of revolting Germans. Grey stillness; grey horrors, in front, and behind amongst the civilian populations! And clear, hard outlines to every thought…Then your batman brought you a cup of tea with a little–quite a little–rum in it. In three of four minutes the whole world changed beneath your eyes. The wire aprons became jolly efficient protections that your skill had devised and for which you might thank God; the broken wheels were convenient landmarks for raiding at night in No Man’s Land. You had to confess that, when you had re-erected that parapet, after it had last been jammed in, your company had made a pretty good job of it. And, even as far as the Germans were concerned, you were there to kill the swine; but you didn’t feel that the thought of them would make you sick beforehand…You were, in fact, a changed man. With a mind of a different specific gravity. You could not even tell that the roseate touches of dawn on the mists were not really the effects of rum…

Therefore he had determined not to touch his grog. But his throat had gone completely dry; so, mechanically, he had reached out for something to drink, checking himself when he had realized what he was doing. But why should his throat be dry? He hadn’t been on the drink. He had not even had any dinner. And why was he in this extraordinary state?…For he was in an extraordinary state. It was because the idea had suddenly occurred to him that his parting from his wife had set him free for his girl…The idea had till then never entered his head.

He said to himself: We must go methodically into this! Methodically into the history of his last day on earth…

(from Part One, Chapter 3)

My online resources for Parade’s End can be found here. If you know of any links that would be helpful to someone reading the work, please let me know and I’ll be happy to add them to the list. OK, on with a hastily written post while I recover from picnic day at UC Davis…

No More Parades, the section of Parade’s End I finished this past week, covers only a little over 200 pages but at some point I found a deeper appreciation for what Ford accomplishes. For those that have read Parade’s End, much of this will be old hat. I’m hoping this discussion, which will focus more on Ford’s style than anything else, will help others reading this work for the first time. Or at least appreciate what is going on long before I did. Like The Good Soldier, writing about what happens in Parade’s End is secondary to how it is told. I also hope to tie in a few points I wanted to raise in Some Do Not… that I neglected in my rush to get something posted last week.

A few basics on the book: Fortunately every recent version I’ve seen of Parade’s End comes with all four novels together in the order of their release. If you are tempted to read them out of order, please resist. The second novel of the tetralogy, No More Parades, takes place in a 48-hour period in France (in or near Rouen) during the middle of January 1918. Since I’m going to shortchange the storyline in this post, some of the action can be found at Mel’s blog The Reading Life:

and

Even though this novel follows a three part structure similar to Some Do Not…, which is mostly chronological but has many layered flashbacks, there are important differences between the two books. Some Do Not… had the feel of a play guided by an omnipresent narrator. In that book we are given glimpses inside the characters’ minds which mostly involve flashbacks. The glimpses into the characters’ minds in this second novel detail the mental state of the characters as they react to what is happening around them. The characters recall past events in order to put current events in context, as well as have dialogues with conscious and unconscious thoughts. Absent or deceased characters also take part in these dialogues because they are present in the active character’s mind. What we end up with is a panoramic novel occuring mostly in the characters’ minds, some chapters never leaving their mind.

One of my favorite sections occurs in Part Two. Sylvia hands Christopher a packet of letters she had not forwarded to him. We watch Christopher read a letter from Mark (Christopher’s brother) through Sylvia’s eyes. She has read the letter already so she recalls Mark’s words while simultaneously giving us her thoughts about what was written. In addition, she provides what Christopher’s reaction appears be to while he reads it. The reader has to keep in mind it is not his true reaction—it is Sylvia’s impression. Another enjoyable section occurs when Christopher finds out Sylvia visited the military base where he is stationed. He is so shaken by her appearance that he attempts to work through his feelings in a methodical, military-like report while trying to make sense of her behavior. At this point he is able to perform this exercise of communicating with himself. In a later chapter, when Christopher reacts to the news from General Campion that he will be sent to the front again, he is unable to perform such a logical examination of his emotional reaction. At this point his thoughts become scattered as he seems close to having a physical and mental breakdown.

Several comments by Ford outline his method in looking at the way the mind works. While General Campion composes letters:

At the end of each sentence that he wrote–and he wrote with increasing satisfaction!–a mind that he was not using said: “What the devil am I going to do with that fellow?” Or: “How the devil is that girl’s name to be kept out of this mess?”

Later, as Tietjens is being interviewed by Campion:

He exclaimed to himself: “By heavens! Is this epilepsy?” He prayed: “Blessed saints, get me spared that!” He exclaimed: “No, it isn’t!…I’ve complete control of my mind. My uppermost mind.”

As I mentioned in one of the Some Do Not… discussions, Parade’s End contains many conflicts, not the least of which is between the “uppermost mind” and the “mind not being used”. By working from inside the minds of his characters, Ford can show these conflicts whether the characters recognize them or not. Tietjens notes this conflict several times, most often when wondering why he feels compelled to defend his wife. His “hidden mind” continually strives to be heard, whether he talks in his sleep or says comments he can’t recall making. Memory also plays a role in his “mind not being used”. The spontaneity with which memories flood the characters’ minds can seem overwhelming at times. The additional layers that memory impacts, such as how the past interacts with today, assists in highlighting Tietjens’ conflict with modernity.

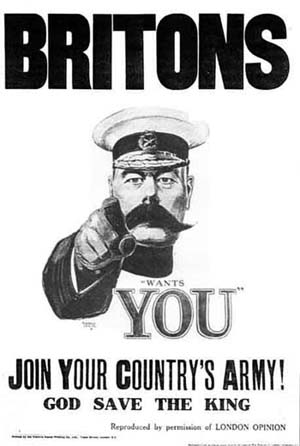

At some point the reader has to address Ford’s view on the war. In some discussions, I’ve raised the point that battle can either destroy a man or make him heroic (and possibly both—I probably talked about this in The Odyssey). Here, war looks like nothing that Homer could have envisioned. Whether we’re looking at weaponry (O Nine Morgan’s death from above as well as Tietjens’ injury in the previous volume), political considerations (threats to move troops to the eastern theater or the sabotaging of the railway lines by unions), or bureaucracy (ordering supplies becomes a farce), the actual face of battle and death has been many time removed from the old portrayal of battle. Ford also portrays the home front, sometimes overlapping with Homer’s focus (at least regarding infidelity). Several times Ford likens war to adultery, both of which he views as inevitable since the desire for both can seem to be part of man’s make-up. I don’t think Ford is nostalgic for the “good old days” regarding warfare. Rather he seems to point out man’s weaknesses or goals, making killing easier (through weapons at longer distances) while at the same time making war much more difficult for those involved (which stretches back to their home).

In addition, how removed are we from previous standards when knighthood can be granted for providing skewed statistics? Or were previous standards just as distorted but a false nostalgia has taken their place? Many writers have covered these points but Ford lets these points develop naturally, almost under the radar. Ford can still be heavy-handed at times. O Nine Morgan’s death and the responsibility Tietjens’ feels for it, especially in comparison to a government sending thousands of men to their deaths for political reasons, seems overplayed at times. Even then, Ford balances such heavy-handedness with General Campion’s philosophy about sending men into battle. He realizes the trade-off of what is needed to fight a battle as well as how to maintain the discipline and respect that are needed. Campion is probably the one character that improved the most in my estimation between the two books—he represents an older view in dealing with the modern world while being the one character that understands Tietjens the most. His philosophy on earning the men’s trust highlights the government’s inability to understand what it takes to lead. A society that lets accomplishment become secondary while arbitrarily handing out rewards will reap what it rewards.

There are several running jokes that Ford seems to have in the series, one of which involves Tietjens’ uniforms. He doesn’t have the physical appearance of a ‘hero’ and his uniforms never quite fit him. But the real gag revolves around how dirty his uniform always appears and how others judge him because of it. In Some Do Not… Sylvia threw a salad bowl at her husband, staining it with olive oil. In this book Campion upbraids Tietjens for wearing shabby uniforms with grease stains on them, causing Christopher to apologize. He finally tells the general that his other uniform was unwearable since O Nine Morgan bled all over it while Tietjens tried to comfort him during his death. Tietjens’ uniform seems to mirror much of the rest of his life, constantly being damaged and judged by others regardless of what caused them to be sullied.

A couple of closing notes:

- How does Sylvia threaten her husband? So far she talks of “corrupting” their son, but Tietjens willingly allows the boy to be brought up as a Roman Catholic. While her behavior has led to the death of his parents (through the help of others), what drains the color from his face is her threat to rip up a tree at his estate. Is this a sign that the past is more important to him than the future?

- There is a decided ambivalence from Ford on Tietjens regarding Christopher’s historical and moral foundations while navigating the modern world, as if Ford is making fun of Christopher while at the same time realizing that such a foundation is needed regardless of the age. Tietjens proves to be an anachronistic character, yet one seemingly needed in (and sacrificed by) the modern world.

One more quote that the more I read, the more I love. This happens inside Sylvia’s mind while she is in a Rouen hotel ballroom with her husband and other partiers. Meanwhile they are under blackout orders, in fear of a German bombing raid, while anti-aircraft guns (stationed next to the hotel) are firing loudly every few minutes:

There occurred to her irreverent mind a sentence of one of the Duchess of Marlborough’s letters to Queen Anne. The duchess had visited the general during one of his campaigns in Flanders. ‘My Lord,’ she wrote, ‘did me the honour three times in his boots!’…The sort of thing she would remember…She would–she would–have tried it on the sergeant-major, just to see Tietjens’ face, for the sergeant-major would not have understood…And who cared if he did!…He was bibulously skirting round the same idea…

But the tumult increased to an incredible volume: even the thrillings of the near-by gramophone of two hundred horse-power, or whatever it was, became mere shimmerings of a gold thread in a drab fabric of sound. She screamed blasphemies that she was hardly aware of knowing. She had to scream against the noise: she was no more responsible for the blasphemy than if she had lost her identity under an anaesthetic. She had lost her identity…She was one of this crowd!

(from Part Two, Chapter 2)

Picture source