Relations by Zsigmond Móricz: solutions?

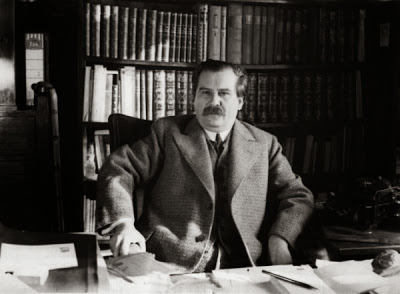

Relations by Zsigmond Móricz

Translated by Bernard Adams

Introduction by George F. Cushing

Corvina Books, Ltd. (2007)

ISBN 978 963 13 5524 6

In my first post on Relations, I included Móricz’s idea for the novel:

When he began to write it Móricz declared, “I postulated the idea that in every family there is one man, the rest are relations. By this I meant that there is a competent, strong personality to whom the many incompetent cling. And this strong man cannot achieve anything, because the network of relations enmeshes him and drags him into the depths.”

But what if he really isn’t competent or a strong man? That’s what we see with Pista, the pawn in the powerful elite’s game. Lina, his wife, understands that there is no such thing as a partial compromise. Pista, seconded by his brother, believes he can make a difference only if he moves in the elite’s circles. Unfortunately he increasingly compromises himself as the novel moves along. Determined not to play the patronage game, Pista’s first thoughts sometimes stray into plans to improve someone’s lot (not illegally, but still through favors). He finds himself behaving more and more like the elite he wants to bring to account, just on a smaller scale.

As the reader finds out more about Pista it’s clear he is not the man for cleaning up the city’s government. His heart is in the right place—his experience as a Russian POW during World War I shaped him:

[H]e had become accustomed to looking respectfully on the mass of unknown, simple people and on every individual among them, for the individual represents the mass, and authority is what the mass expects…He’d had plenty of time to learn that lesson in the Russian prison camp, but the upper classes here at home, and the women in particular, hadn’t been through that school and could still behave to isolated individuals with effortless superiority and tyrannical manners. (138)

Pista had harbored a secret plan to reorganize the school Assistance Board to help provide schoolbooks to all children. Nothing had come of it so far. First there was the war, then he was captured, and he was not able to help in his post as Cultural Adviser. It’s a minor point, but it helps highlight that Pista is a dreamer and planner, not a doer. A lot of the bleakness of the novel comes from this point, where a good man is unable to make any changes to a corrupt system.

In the introductory essay George F. Cushing mentions that Móricz provides solutions to the problems he outlines. I find the solutions ambiguous, though, as indefinite as the impossibility of implementing them. During the return train ride back from Budapest Pista muses about the unsatisfactory trip, the county official he is traveling with, and how things could improve. As he looks at the county official he thinks:

This was just a living human being, interested only in his own close circle of affairs. Who saw no farther than the County boundary, and even within that couldn’t think anything through or arrange things properly. There was a kind of bureaucratic system according to which things had to be done, but how should he think, for instance, of something higher, such as how to find work for the thirty thousand unemployed in the County? Thirty thousand men, agricultural workers, marvelous material. The country could be built with these thirty thousand. Roads, houses, schools, museums. All it needed was somebody to set the thirty thousand to work. A will, a power aiming at a goal. The whole country could be re-organized with just these thirty thousand. (120-121)

As much as this is a call to action, looking for a will or a power that will lead rather than skim money, it’s contradicted by other scenes in the book. The funds to do something like this aren’t available–they have been stolen or lost. The County begs for loans and handouts in order to stay afloat (again, the chain of patronage is present at every level). Even if the funds were available, how many of the thirty thousand would want to work? The unemployed men in the novel range from industrious to loafers. The industrious men are often schemers, like Pista’s uncle who is industrious only in his schemes. Pista’s generosity toward family members rarely provide any structural help, instead leading to more dependence, something that also seems bred into the “chain of patronage.”

Pista’s political philosophy was aligned with the Opposition party decrying the parasitic nature of the government. From Dr. Martiny, the leader of the Opposition:

“It really boils down to who the world belongs to. Capital? Or the workers? Or the State? What’s certain these days is that the State isn’t organised for the benefit of the people. It enjoys an exceptional position, like the ancient oligarchies. In the eyes of the people the State is a mystic power. An end in itself. Human life isn’t important, what matters is for the State to flourish. The State devours its children. It’s a real Cronos. They say we live in a State. No: the State lives on us.” (149)

And yet Dr. Martiny paints an extremely bleak view of man with his emphasis on peasants not ready for their freedom. He maintains that freedom for the peasants would be a disaster because they wouldn’t know what to do with it. He says that man yearns for dependence, not independence. I guess being kept on a short leash is better than being devoured, but is that the best man can hope for? Likewise the recommendation of Pista for “bush farms” to improve the farmers’ lot comes with a dreary twist. While his advice does make sense in a world where farm commodity prices are falling, he sells it to the corrupt administration with the promise that the government will have more direct control over the farmers. So to Cushing’s point—there are solutions proposed but each one has drawbacks. Despite the humor (and I think there is more than he gives credit) there is at the core of the novel a bleak view: at best, incremental improvement is all Hungary can hope for given the state of the government and the people.

The reason Pista was chosen as a figurehead Town Clerk, which would allow the elite to remain in power, was that he was related (or rather his wife was) to one of the elites. At first the novel seemed to be going in a Being There direction, with Pista uttering banal phrases that draw applause from the public and leaders for their supposed insight. But Pista is no Chauncey Gardener. There is substance below the surface, it’s just that he is out of his league with these leaders. He finds his good intentions thwarted early and often, causing him to despair immediately. “All of a sudden he saw his life as hopeless. What did it all matter if one stood alone and couldn’t live by those principles that ruled one, that made life worth living?” (92) So what are his options? Pista wants to fight the patronage system by promoting men of worth, some of whom are conveniently family members. He feels he can trust family as much as he trusts himself, showing his faith is misplaced on both sides of the equation, fighting patronage with patronage.

Móricz provides disturbing hints in the novel about the complete loss a family experiences when the head of the household dies, especially by suicide. The uselessness of fighting adds to the bleak tone: “A man struggles and fights, sticks at nothing… When he dies, the whole thing collapses like a balloon when the air leaks out.” (79; ellipsis in original) After the all-night party, Pista realizes he has been played by virtuosos. The Mayor, someone Pista has dismissed as old and doddering, delivers a fascinating and masterful speech to Pista, undermining everything he has tried to accomplish. The intent was to deflate Pista’s ego and ideas so that he would more easily fall in line with what the elite wanted to accomplish. Instead he gives in to despair even though he knows the cost to his family. We don’t know whether or not he was successful in his suicide attempt, but that he attempted to kill himself knowing the cost to his family shows the depths he reached. The Mayor, realizing what a good man (to their corrupt cause) Pista would be, demands help for the Town Clerk and his family. This proves to be Móricz’s coup de grace for the optimism of improvement in the country: what had been hope for bettering the area is now only of use to those people stealing everyone blind.

Related posts:

“The only relation to love is the one that’s of use to you”: problems in post-World War I Hungary

Lina and Magdaléna

Introduction to Móricz and the novel

My notes