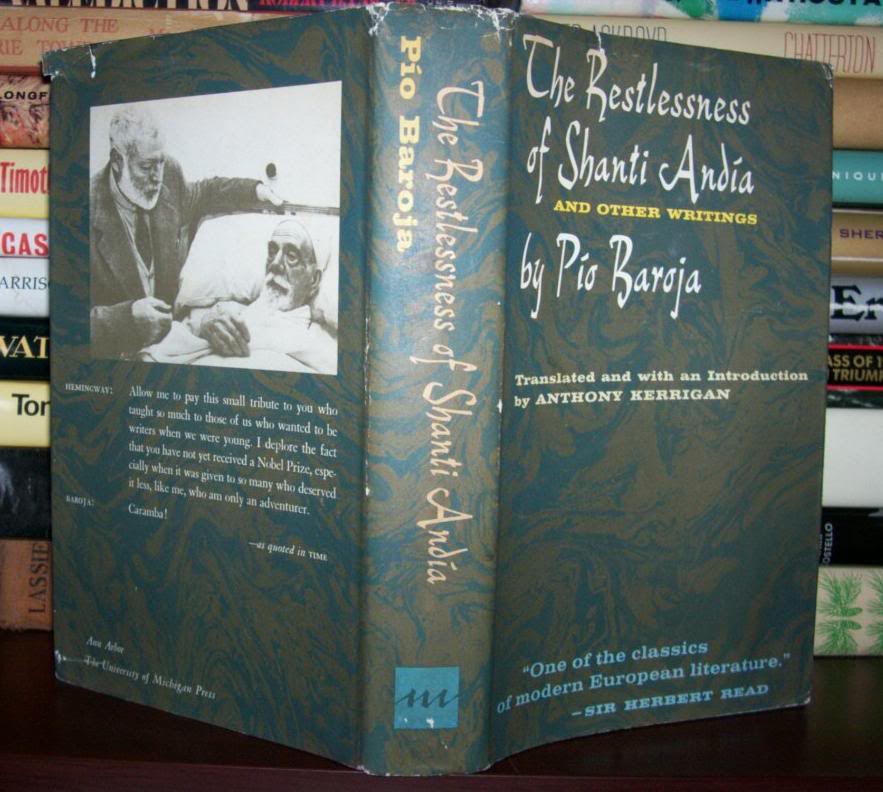

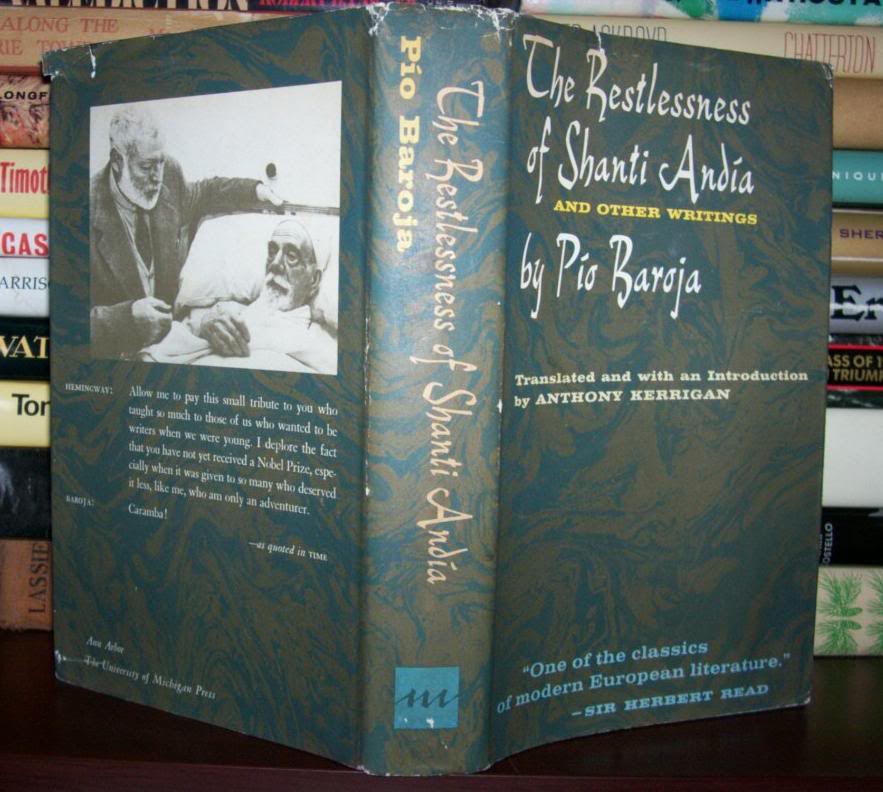

The Restlessness of Shanti Andía online resources

Translated and with an introduction by Anthony Kerrigan

(The University of Michigan Press, 1959)

Picture source

Text on the back:

HEMINGWAY: Allow me to pay this small tribute to you who taught so much to those of us who wanted to be writers when we were young. I deplore the fact that you have not yet received a Nobel Prize, especially when it was given to so many who deserved it less, like me, who am only an adventurer.

BAROJA: Caramba!

– as quoted in TIME

“Before [1898], in the period of adventures, Spain was led by Don Quixote. From now on, it would be directed by Sancho Panza.” – Pío Baroja

This will be a different type of resources post since there is little available (in English) on Baroja and The Restlessness of Shanti Andía. I included more excerpts than usual from a variety of sources. Hopefully this will help introduce the author and some of his works.

Pío Baroja

The Wikipedia entry for Baroja

More on the Generation of 1898 at Wikipedia

H. L. Mencken on Baroja, in the introduction of Youth and Egolatry

Baroja, then, stands for the modern Spanish mind at its most enlightened. He is the Spaniard of education and worldly wisdom, detached from the mediaeval imbecilities of the old regime and yet aloof from the worse follies of the demagogues who now rage in the country. Vastly less picturesque than Blasco Ibanez, he is nearer the normal Spaniard–the Spaniard who, in the long run, must erect a new structure of society upon the half archaic and half Utopian chaos now reigning in the peninsula.

From the biographical sketch at the The University of Texas’ Baroja collection

Baroja lived a fairly quiet and sedentary life in Spain, but would occasionally travel through Europe, especially to France, England, and Italy. During his travels he met other literary luminaries like Oscar Wilde and Spanish poet Antonio Machado, and he accumulated an impressive library of books about witchcraft and the occult. In July 1936, at the start of the Spanish Civil War, Baroja was imprisoned as “an enemy of tradition.” Even though a member of the army recognized Baroja as a famous author and released him after a single night in jail, Baroja was outraged and moved to France. He didn’t return until the end of the war in 1939.

Chapter 5 of Rosinante: To The Road Again by John Dos Passos, titled “A Novelist of Revolution”. Excerpt:

From the first Spanish discoveries in America till the time of our own New England clipper ships, the Basque coast was the backbone of Spanish trade. The three provinces were the only ones which kept their privileges and their municipal liberties all through the process of the centralizing of the Spanish monarchy with cross and faggot, which historians call the great period of Spain. The rocky inlets in the mountains were full of shipyards that turned out privateers and merchantmen manned by lanky broad-shouldered men with hard red-beaked faces and huge hands coarsened by generations of straining on heavy oars and halyards,–men who feared only God and the sea-spirits of their strange mythology and were a law unto themselves, adventurers and bigots.

It was not till the Nineteenth century that the Carlist wars and the passing of sailing ships broke the prosperous independence of the Basque provinces and threw them once for all into the main current of Spanish life. Now papermills take the place of shipyards, and instead of the great fleet that went off every year to fish the Newfoundland and Iceland banks, a few steam trawlers harry the sardines in the Bay of Biscay. The world war, too, did much to make Bilboa one of the industrial centers of Spain, even restoring in some measure the ancient prosperity of its shipping. …

“I have never hidden my admirations in literature. They have been and are Dickens, Balzac, Poe, Dostoievski and, now, Stendhal . . .” writes Baroja in the preface to the Nelson edition of La Dama Errante (“The Wandering Lady”). He follows particularly in the footprints of Balzac in that he is primarily a historian of morals, who has made a fairly consistent attempt to cover the world he lived in. With Dostoievski there is a kinship in the passionate hatred of cruelty and stupidity that crops out everywhere in his work. I have never found any trace of influence of the other three. To be sure there are a few early sketches in the manner of Poe, but in respect to form he is much more in the purely chaotic tradition of the picaresque novel he despises than in that of the American theorist.

Baroja’s most important work lies in the four series of novels of the Spanish life he lived, in Madrid, in the provincial towns where he practiced medicine, and in the Basque country where he had been brought up. The foundation of these was laid by El Arbol de la Ciencia (“The Tree of Knowledge”), a novel half autobiographical describing the life and death of a doctor, giving a picture of existence in Madrid and then in two Spanish provincial towns. Its tremendously vivid painting of inertia and the deadening under its weight of intellectual effort made a very profound impression in Spain. Two novels about the anarchist movement followed it, La Dama Errante, which describes the state of mind of forward-looking Spaniards at the time of the famous anarchist attempt on the lives of the king and queen the day of their marriage, and La Ciudad de la Niebla, about the Spanish colony in London. Then came the series called La Busca (“The Search”), which to me is Baroja’s best work, and one of the most interesting things published in Europe in the last decade. It deals with the lowest and most miserable life in Madrid and is written with a cold acidity which Maupassant would have envied and is permeated by a human vividness that I do not think Maupassant could have achieved. All three novels, La Busca, Mala Hierba, and Aurora Roja, deal with the drifting of a typical uneducated Spanish boy, son of a maid of all work in a boarding house, through different strata of Madrid life. They give a sense of unadorned reality very rare in any literature, and besides their power as novels are immensely interesting as sheer natural history. The type of the golfo is a literary discovery comparable with that of Sancho Panza by Cervántes.

At the blog Oreneta is a “translation of the chapter in Pío Baroja’s serialised novel The adventures, inventions and mystifications of Silvester Paradox / Aventuras, inventos y mixtificaciones de Silvestre Paradox (1901) in which Silvester takes up with an English conman, quack, amateur pugilist and exponent of inventions such as the translatoscope called Macbeth.”

The opening lines of Camilo José Cela’s Nobel prize acceptance speech:

“My old friend and mentor Pío Baroja – who did not receive the Nobel Prize because the bright light of success does not always fall on the righteous – had a clock on his wall. Around the face of that clock there were words of enlightenment, a saying that made you tremble as the hands of the clock moved round. It said ‘Each hour wounds; the last hour kills’.”

The Restlessness of Shanti Andía

TIME magazine’s article on the book (from 1959):

Don Pio is one of Spain’s greatest 20th century novelists; yet many of the elements of Shanti Andia have an old-fashioned ring. The story is laid along the Basque seacoast of the eigth [sic–should be nineteenth] century. There is a duel, a mutiny, piracy, the slave trade, an escape from prison, changed identities, a kidnaping, even buried treasure. The high adventure is made believable by the style—dry, direct, understated. But the excitement is only incidental to the story’s main theme, which is Shanti’s lifelong pursuit of truth and his stoic acceptance of whatever roadblocks fate may put in his path.

From an article by Julio Caro Baroja, 1972, found at Ute Körner, Literary Agent, S.L.:

As a result, reviving his images of the small ports of Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya, and fitting certain elements in with others, he composed this sea novel all in one breath of inspiration, leaving us a work which is not the classic adventure novel but one which contains different and loftier values.

Book contents:

Book 1: Childhood

Book 2: Youth

Book 3: The Return Home

Book 4: A Dutch Hooker called the “Dragon”

Book 5: Juan Machín, Miner

Book 6: La Shele

Book 7: Juan de Aguirre’s Manuscript

Kroh

Fascinating stuff on a forgotten literary giant. Any idea where one can find English translations of La Dama Errante and La Ciudad de la Niebla? It would be a huge help.

Dwight

Sadly I can find little on English translations other than in University libraries. I work not too far from the Stanford University library, but have not had the time to investigate the cost of non-students checking out books.

If anyone else knows where translations can be found, please feel free to chime in!