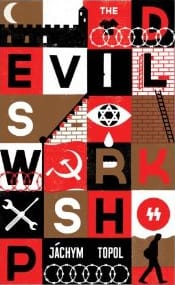

The Devil’s Workshop by Jáchym Topol

Translated from the Czech by Alex Zucker

Portobello Books, 2013

(original book published in 2009)

Readers to this book are likely aware, more or less, of the basic facts of the genocide of European Jews in the Second World War. Yet the mass killings of non-Jewish Belarusians during the same period have only recently been dragged out of the shadows, thanks to US historian Timothy Snyder’s tour de force of 2010, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. So even though The Devil’s Workshop is a work of fiction, readers should know that on 22 March 1943, the 18th Schutzmannschaft auxiliary police battalion (made up largely of Ukrainian collaborators, deserters, and prisoners of war) and the Wafer-SS special battalion led by the notorious Oskar Dirlewanger murdered the inhabitants of Khatyn—149 Belarusian children, women, and men—and this is a fact. As Snyder wrote in Bloodlands: ‘Dirlewanger’s preferred method was to herd the local population inside a barn, set the barn on fire, and then shoot with machine guns anyone who tried to escape.’ This is the method he used in Khatyn and it is described in Topol’s book by one of the story’s fictional characters.

– From the Translator’s Afterword

In starting to post again I realize I’m extremely rusty at doing this, so please forgive my stumbling language and lurching from one topic to another. Hopefully I’ll get my feet again soon…not that they were ever completely underneath me.

The Devil’s Workshop explores Holocaust memory through satire and Topol’s approach surprisingly (to me) works. He examines some of the different ways people remember the Holocaust as well as examining what it was/is like to live under Communism and in Belarus’ post-Communist dictatorship. Blending fact and fiction, Topol looks not just at the varying ways individuals reconcile themselves to the Holocaust and its dehumanization but also explores the political and commercial aspects of its remembrance.

The book starts with a nameless narrator growing up in Terezín, a former Czech fortress town that was home to a concentration camp during World War II. We follow the narrator from his youth shortly after the war, where he explores the ruins of the site under the oversight of Uncle Lebo, to around the time the Czechoslovakian Communist regime fell. During that period the camp sank into ruins and the state of the government monument and grounds of the camp declined as well.

A movement starts in Terezín, organically from a few of the locals and well meaning tourists, to resuscitate the town and tout it as a Holocaust sightseeing site. The movement is quickly hijacked by people wanting to use it for their own political purposes and unlock its enormous commercial/monetary potential. The narrator, as one of the true insiders of the Terezín memorial business and its only computer expert, is recruited to bring the donor list to Minsk, Belarus so the Khatyn massacre site can be developed and monetarily mined in the same manner.

The second half of the book follows the misadventures in and around Minsk as the narrator meets people excavating human remains from a massacre site and establishing a museum. It’s at this point that the satire turns much darker. The atmosphere at the time makes the endeavor a potential landmine as dissidents and entrenched power use the Holocaust memory for their own political purposes. Worse, the people in charge of the excavation and museum establishment have an extremely perverse sense on how the Holocaust should be remembered.

So where is Topol’s criticism aimed? It seems to be directed at everyone, and that is what makes it so compelling. In no particular order…

The journalist Rolf sets the revitalization of the camp in motion with his articles. He claims he wants to “feed the memory of the world,” but he seems more interested in material for his pieces and the praise and reaction they get. “You’re in the heart of darkness here, touching the depths of horror, it’s irresistible!” Was he interested in spreading what actually happened or was it just a self-aggrandizing exercise?

Many of the tourists are targeted with Topol’s scorn as well. A large percentage are seen as either spoiled western kids living off of daddy’s credit cards or tourists viewing the (government-backed) monument as another St. Mark’s or gondola ride in Venice to experience. There are others though who show up, “crazed with pain,” who want to try and understand what happened. Regarding one such visitor: “I had the feeling she was recuperating, coming out of her grief, escaping the despair that can cloud a mind with blackness and, especially in young and innocent people, produce a shock of realization at how terrible evil is.”

The question seems to be, though, what do you do with that despair? One traveler who stays in Terezín starts selling chintzy souvenirs (in horrible taste) to tourists, but that just feeds an enterprise quickly hijacked for monetary gains. She admits to the narrator that she feels superior to those living in eastern Europe, thinking their complexes and hang-ups are inferior to hers. Another visitor, though, rebounds from suicidal despair in a manner that helps the marginalized inhabitants of Terezín.

The governments come in for their fair share of abuse. Both the Czech Republic and Belarus are shown as wanting to spin the story of the Holocaust in their own favor, or at least avoid any blame on inhabitants of their countries. As the chief excavator at a massacre site puts it, “Yes, now we will dig in the dirt where the tyrants forced your parents and grandparents to kneel. You know as well as I do that this government won’t allow a word about Belarusians murdering one another. But we will shatter the silence! To forget the horrors of the past is to consent to a new evil.” It sounds good until you see he’s willing to sacrifice those helping him, writing their arrests and injuries off with a shrug for the common good.

So where does that leave us? I’ll steal the following quote from Rajendra Chitnis, associate professor of Czech at University College Oxford, since it follows my thoughts on the book and puts them much more succinctly and clearly than I can (found at the Radio Prague link below):

I think it’s a book that is using the very well understood and difficult case of the Holocaust to think about how we do come to terms with the past and particularly how people who live in that region come to terms with all of the past – not just the Holocaust, but also Communism. Of course this has been a big topic in that part of the world since 1989 and I think Topol’s rather difficult answer is that there isn’t a way of coming to terms with these things.

I think his point is that human beings struggle to deal with the memory of terrible violence. And all of the strategies that we choose in the end are in some ways inadequate to the actual incident. And particularly I think feel inadequate to people who live after them. It’s extremely difficult for them to be surrounded all the time by the memory of these events. They find it very difficult to find a way to commemorate them properly and understand them properly and feel that they have done justice.

It’s a very difficult and disturbing and disorientating book to read because I think Topol wants to give the reader some vague sense at least of the reality of that history rather than the nicely packaged version that we get when we visit the main tourist destinations in the region. …

What he shows is that those who were alive were all implicated in the violence and those who lived afterwards are all implicated in our failure to remember it properly.

I’m a little late to posting about this book since there are many reviews available, but I wanted to end with an irony in the book I haven’t seen called out as such. While serving a prison sentence, the narrator inadvertently became the person assigned to escort condemned men to the death chamber. This makes him a target of deathly hatred among the inmates and impacts his life outside of prison. Choices he makes on the outside often revolve around his complicity in the deaths of those prisoners. I realize it’s a modest example on a smaller scale in comparison to what the rest of the book is exploring, but it helps frame the larger topic in an understandable manner.

A quick note on Alex Zucker, the translator of the book: As you can see from his website, he has quite a few translations from Czech to English to his credit and it looks like there are more on the way. While I’ve never met him, Alex has been most gracious in answering questions I’ve had via email and provided suggestions and comments that were extremely helpful. Here’s hoping there are more works on the way from him. Be sure to check out the translations he has had published. There are some gems there.

A few links:

- History of Terezin educational site

- The Czech Center’s The history of the Terezin Concentration Camp

- Radio Prague’s note on the book from their Czech Books You Must Read series, with helpful insight from Rajendra Chitnis

- Profile of Belarus

- The Khatyn Massacre: “But the fact that massacres of this kind, isolated incidents within their countries, took place ‘on a scale incomparably greater’ in the Soviet Union is largely overlooked.”

Chladnou zemí (Through a Cold Land)

Czech title of English translation The Devil’s Workshop