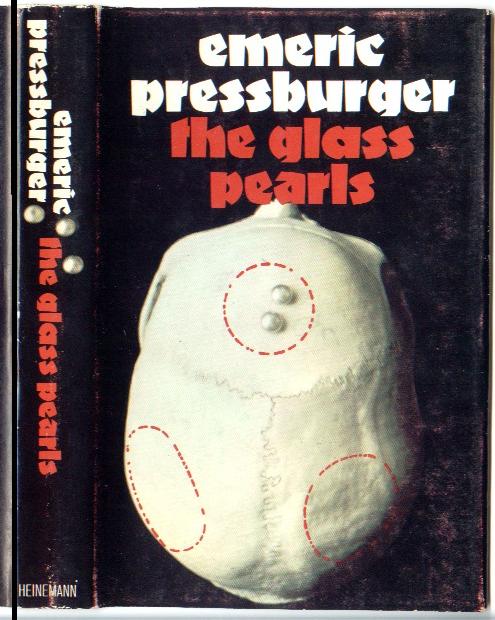

The Glass Pearls by Emeric Pressburger

The Glass Pearls by Emeric Pressburger

London: William Heinemann Ltd, 1966

Hardcover, 210 pages

Lucy Scholes’ article “Emeric Pressburger’s Lost Nazi Novel” at The Paris Review blog got my attention for several reasons. I’ve enjoyed several of the Powell and Pressburger movies and wanted to see how his talent from the screen would translate to the page. The ‘twist,’ finding out immediately that the main character is a Nazi war criminal, made me want to see what the focus of the book would be. Also, saying a well-written book “sadly remains largely unknown and unread” feels like a personal challenge for me to find and read it.

Scholes’ article is a great introduction to the work as well as providing insight into Pressburger’s life and its tie-in to the novel, so I highly recommend reading it. In addition, there are two online reviews I found (after I finished the book) that I also recommend since they add more angles to the story and tie-ins to Pressburger’s life:

These three reviews/posts cover a lot about the book, so I will try to focus on different angles in the story as well as cover some of the same territory in case this is your introduction to the book. I know there will be a lot of overlap with those posts. I know I’m revealing much of the story, but the power of the book comes from the questions raised and the way Pressburger chooses to raise them.

The book begins early in June 1965 with the piano tuner Karl Braun moving into his new flat on Pimlico Road in London. We find out right away, through a flashback to earlier that year, that Braun is really a Nazi war criminal with the real name of Dr. Otto Reitmüller. In the four years he performed operations on concentration camp prisoners he removed parts of their brain and had them repeat stories, “vivid memories from their lives,” in order to note discrepancies with previous narrations of those stories. He would repeat the process until the patient died, usually by the third brain operation.

While the focus of the book is on Braun, one of the recurring questions explored in the book is what it takes for a person to volunteer to be in such a medical trial. It’s a difficult question that’s hard to answer without being in that situation. As one of Braun’s London neighbors puts it to a fellow boarder,

“If you’d been told…you’ve got the choice: either you join the others and proceed into the slaughter-house [gas chambers] now—or you could enter the hospital where there will be food, clean sheets, for as long as three to four months. Either you’ll be exterminated like vermin tonight, or, I, the famous researcher working to solve the secrets of the human mind, will carry out some experiments on you. Which would you have chosen?” (204-5)

The flip side of that question is why Braun performed those experiments. His cold-blooded, analytical mind generates nightmares about being caught and tried for war crimes, but his subconscious comes up with reasons why he would be released. The courtroom should symbolize “the people’s wish: to be judged by its own conscience and thus purify itself of the deeds of the past.” (11) The defense counsel in his dream essentially gives the “just following orders” defense without using those words, and his nightmares resolve in his favor. The self-importance he feels in what he has contributed to science is monumental, since he “did all the spade-work to discover how memory was stored in the brain, who carried out his unique experiments using his advanced technique of surgery on the living human brain.” (166) Which is, of course, precisely the problem. These patients weren’t given a true choice.

Braun has been dating a divorcee, Helen Taylor, who keeps him at arm’s length, at least physically. In response to Helen’s repeated questioning of his past, Braun tells of being a press photographer. Helen provides one of the deepest insights into Braun and the “following orders” excuse, although ironically, since she is talking about his job as a photographer instead of a doctor.

Helen: “You’re obstinate when you want to gain your end. I can imagine when you were still a press-photographer, you always got the pictures you were after. No matter whether it embarrassed your victim or not. You didn’t care a damn about the suffering of your victims. Am I right?”

Braun: “What on earth are you talking about?”

Helen: “I know what I’m talking about. Don’t press-photographers invade the privacy of people?”

Braun: “It’s the duty of a press-photographer to photograph the news. It is his job. The readers expect nothing less from him.”

Helen: “Alcoholics expect alcohol. Drug-addicts expect drugs. Sex-maniacs expect to rape little girls. I hate people to say that they do things because it’s expected from them. It depends on you alone whether you do things or you don’t. …”

Braun: “If one reporter doesn’t do it, another will.”

Helen: “Let him. The first reporter could say, ‘I haven’t done it and I’m proud of it.'”

(156)

Despite claims that Pressburger makes Braun a sympathetic character, I felt the approach was closer to trying to understand and maybe even empathizing with someone who has made the choices Braun has made, as well as exploring what it takes for him to survive in a world where he is a fugitive. The reader follows Braun through his humdrum daily routine and to his nights at classical concerts. One of the ironies of the book lies in Braun having to hide his past, similar to how Jews had to live in Nazi German-occupied territory hiding their heritage in order to avoid the concentration camps. Braun, of course, has the advantage of being able to live in the open despite feeling like a prisoner, and his story of escaping Germany before the war started draws sympathy from other characters. Pressburger does allow one character to heavy-handedly and directly express the general opinion toward the experiments: “The kind of man you are describing [a “famous researcher working to solve the secrets of the human mind”] belongs to the most common and most dangerous kind of criminals. They are the scourge of the human race. Those who can explain everything. Who commit their crimes int he name of Science, the Fatherland, Religion, for the sake of Love, Culture, for Progress.” (205)

There are several events that heighten Braun’s paranoia and despair. A visit from a Nazi colleague earlier that year had made him aware of the statute of limitations for war crimes, which had been scheduled to expire in May 1965, would be extended five years. The colleague had begged Braun to return with him to Argentina and join a community of former Nazis living there, but the thought initially repulsed Braun. “He shuddered at the thought of spending the rest of his life among disgruntled sexagenarians who had one single purpose in life: to become octogenarians.” (146) He realizes, though, that all he wants is peace and rest from having to continually hide from his past, so he plans to draw money from his secret war stash and travel to Buenos Ares. While the approach of the anniversary of the death of his wife and child in the bombing of Hamburg always unsettled him, this year is worse as many acquaintances try to include him in their activities on that day. To make matters worse for Braun, the trial of an assistant in the concentration camp hospital makes him aware that his research diary was in the hands of the authorities. All of these things together heightened Braun’s paranoia, so when he believes someone is following him his baser “survive at any cost” instincts kick in and we find he is still capable of unbounded cruelty.

The question of memory repeatedly comes up in the book. I won’t provide the spoiler here, but if you don’t believe you’ll read the book and want to know more, go to sovay’s post. The paragraph that begins, “In the very last pages of the book” reveals a powerful twist to both the story and how part of it derives from Pressburger’s life. In addition, the last quote in that paragraph is one of the last lines in the book and mentions that the patient Braun was experimenting on died “somewhere on page 183” of Braun’s research diary. Coincidentally (or maybe not), Page 183 in The Glass Pearls is when Braun finds out that authorities have his research diary, changing the course of his plans and leads to his destruction.

There is so much more I could write about the book, but I need to close this post before it rambles on too long. Pressburger provides a haunting character study of a man similar to some of the most monstrous actors in World War II, one I won’t forget soon. It’s a powerful book, one I immensely enjoyed and recommend very highly.

Links:

-

- Faber & Faber reprinted the book in 2015 with “two new introductions, by cinema scholar Caitlin McDonald and by Pressburger’s grandson, the Oscar-winning film director Kevin MacDonald.” I read the original 1966 release, but with a little searching I was able to find the new introductions online. According to Pressburger’s Wikipedia page, “Kevin has written a biography of his grandfather, and a documentary about his life, The Making of an Englishman (1995).” In sovay’s article linked above, McDonald’s book Emeric Pressburger: The Life and Death of a Screenwriter (1994) is mentioned when listing some of the facts from the book that tie directly to Pressburger’s life.

-

- At the Powell & Pressburger Pages site is The Writing of Emetic Pressburger page.