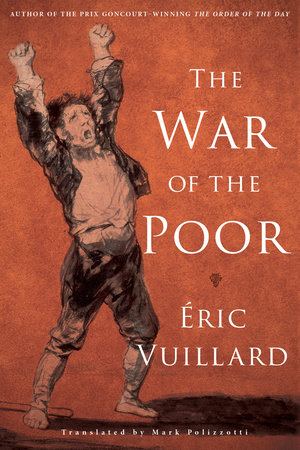

The War on the Poor by Éric Vuillard

The War on the Poor by Éric Vuillard

Translation by Mark Polizzotti

Other Press, 2020

I have been reading a few books about the Peasants’ War of 1524-25, a somewhat timely endeavor since we’re at the 500 year mark of the war’s culmination. I was going to post on one book I thought extremely well done and could recommend (once I finish it) when I noticed I had a brief draft from 2021 on this slim book by Éric Vuillard, for some reason unposted. So I went back and re-read the book to see if I wanted to make any changes to my draft and actually post it. With some hesitation, I’ve made a few minor tweaks and added an update and decided to post it. Finally.

“They say literature gives you license.” That is a quote from Éric Vuillard’s book The Order of the Day, and he liberally uses that license when writing about the German Peasants’ War of 1524-25. I’m not quite sure how to describe this book. Saying it is an impressionistic, interpretative essay on the life of Thomas Müntzer and his role in the uprising might come close. I’m sure others have a better description. Here is an excerpt from pages 48-9 to give you a taste of the style and maybe the heart of the book:

Yes, Müntzer is violent; yes, Müntzer is a raving loon. He calls for the Kingdom of God here and now—there’s impatience for you! The inflamed are like that: They spring forth one fine day from the head of the populace the way ghosts seep from walls.

But by what treasure of distance and delegation, by what twists and turns of the soul are the great sophisms of power maintained? One could write a history—nuanced, subtle, wildly improbable; but also shameful, with a thousand doses of poison, of lies proffered, fabricated, admitted, believed, repeated; of sincere prejudices, secret, half-avowed guilty consciences, and all the contortions of which the soul is capable.

Still, between two long periods of struggle, voices arise. The more regular the pain, the more staccato the voices. The more unanimous the authority, the more singular the voices. Müntzer is a voice. He cries out that, princes or servants, rich or poor, God molded us from the same gutter mud, whittled us from the same sandalwood.

Müntzer is a crackpot, fair enough. Sectarian. Yes. Messianic. Yes. Intolerant. Yes. Bitter. Perhaps. Alone. Sort of. Here’s what he said: “Behold, I have put my words in your mouth; I have this day set you over the nations and over the kingdoms, to root out, and to pull down, and to destroy, and to throw down, to build, and to plant.”

Vuillard briefly details some of the antecedents of the war, such as Wycliffe’s English translation of the Bible, John Ball’s and Wat Tyler’s roles in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, Jack Cade’s manifesto and the 1450 revolt, and Jan Hus’ early attempt at reformation (before anyone probably contemplated what that would actually entail).

The remainder of the text focuses on Müntzer as he gives voice to social and religious grievances of the peasants in Germany. It’s a breezy, wild ride following Vuillard’s prose, which is usually light on details to substantiate the impressions conveyed. Religion is included as a motivation but the emphasis seems to be on economic and social aspects of the uprising. In this respect he seems to loosely follow Friedrich Engels’ approach to the war, even though some of his claims directly contradict Engels. His focus on Müntzer narrows the scope of the uprisings that occurred all across Germany, but I don’t think Vuillard intended a complete coverage of the war.

Which raises the question—what is the intent of the book? To provide a parallel between that war and modern-day social and economic grievances? Maybe the use of the word “poor” in the title instead of “peasants” helps reinforce that interpretation. The publishers summary blurb, “Vuillard draws insights from this revolt from nearly five hundred years ago, which remains shockingly relevant to the dire inequities we face today,” makes that interpretation explicit. Those “insights,” though, seem more blurred in the actual text.

For one example: what is intended in the descriptions used for Müntzer quoted above: crackpot, sectarian, intolerant, etc. Are they meant ironically, more how he was judged during the day versus what he was actually striving for? Did other forces influence the changes Müntzer was hoping to see, and/or did they provide a better or worse way of dealing with the inequalities than what he was proposing?

With all that said, I somewhat enjoyed the book. Its succinctness and compression may actually work in its favor. Vuillard touches on many of the issues raised in the uprising in an effective way, some of which can be credibly used today. That being said, I wouldn’t recommend it to someone wanting to dig deep into the Peasants’ War, but maybe it would be a good gloss or impression for someone wanting to get a flavor of what was contended during this period. I’ll have more on the Peasants’ War after I get a few more books out of the way.

- Links:

- The first two chapters at Other Press

- Thomas Müntzer—So Who Was He? by Andy Drummond (a site “put together by a Müntzer enthusiast based in Edinburgh, Scotland”). His page on Müntzer contains links to his biography, some of his writings, an online bibliography, images and maps, and additional helpful links. This looks to be a great starting place for anyone wanting to explore more about Müntzer’s life and writings.

- Update: I see that Andy Drummond has had a biography on Muntzer published. See his page for more information on his book.