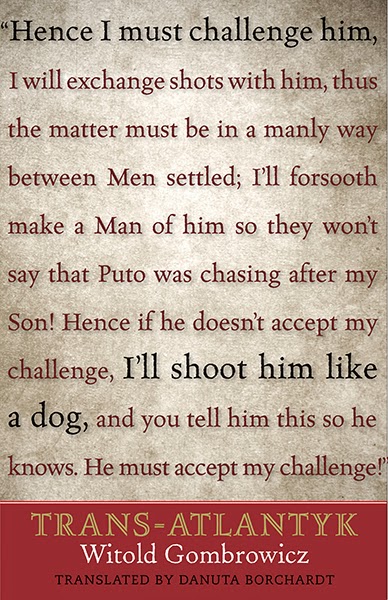

Trans-Atlantyk by Witold Gombrowicz: taking on bigger beasts

An Alternate Translation by Danuta Borchardt

Yale University Press

ISBN 978-0-300-17530-1

Czesław Miłosz in The History of Polish Literature:

For Gombrowicz, there is always both a striving toward liberation from “the form” and a necessary submission to it, since ever antiform freezes into a new form. Each book of his, however, is a renewed attempt to capture one variety of striving and to smash one more sacrosanct rule of art.

…

His novel Transatlantic (Transatlantyk, 1953), has an Argentinian setting but is written in a language that parodies Polish seventeenth-century memorialists. Many consider it his most accomplished work, as it brings into the open a theme underlying all he writings: how to transform one’s “Polishness,” which is felt as a wound, an affliction, into a source of strength. A Pole is an immature human being, an adolescent, and this saves him from settling into a “form.”

The History of Polish Literature by Czesław Miłosz (London: The Macmillan Company, 1969; page 434)

The new translation provides the preface to the 1957 Edition of Trans-Atlantyk:

Has any author explained his work as much as Gombrowicz?

“On this scale of things the best opinion I could hope for would be one that sees in this work “a national self-examination” as well as a “criticism of our national flaws.” (xvi)

“I do not deny: Trans-Atlantyk is, among other things, a satire. It is also, among other things, a rather intense reckoning…but, obviously, not with the Poland of our time, but with the Poland that has been reated by her historical existence and her location in the world (this means a w e a k Poland). And I concur that Trans-Atlantyk is a corsair ship that smuggles a lot of dynamite in order to explode our hitherto-felt national emotions. It even conceals within it a requirement of sorts with regard to certain emotions: to overcome Polishness. To loosen up our submission to Poland! To break away just a little! Rise from our knees! To reveal, legalize another dimension of feeling which orders a human being to defend himself against his nation as against any collective force. To obtain—this is most important—freedom from the Polish form, while being a Pole to be someone larger and higher than a Pole! Here it is—Trans-Atlanthk’s ideological contraband. This might mean a very far-reaching revision of our relationship to the nation—so far-reaching that it might totally transform our frame of mind and liberate energies that would, as the final outcome, be useful to the nation. A revision, nota benne, of a universal character—I might propose this to peoples of other nations, because the problem is not only the relationship of a Pole to Poland but that of any human being to his nation. And finally a revision as it most closely relates to all the contemporary problems, because I have my sights (as always) on strengthening, enriching, the life of the individual, making him more resistant to the oppressive superiority of the masses. This is the ideological mode in which Trans-Atlantyk is written. (xvi-xvii; ellipsis in original)

Gombrowicz doesn’t aim low, does he? But then, “I am one of those ambitious shooters who, if they botch things up, it’s because they take on bigger beasts.” (xvi)

In the next breath, though, he dismisses his own statement by saying “Trans-Atlantyk does not have a subject beyond the story that it is telling” (xvii) and that it has “a multitude of meanings.” (xviii) He declares he has only written about himself, while at the same time talking about much bigger topics.

More on the book in the next post later this week.

Related post: Worthless and futile emotions