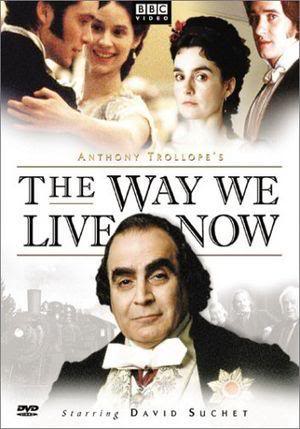

The Way We Live Now: 2001 TV series

I just finished watching the TV series of Trollope’s novel adapted by Andrew Davies and David Yates. Despite some major changes in characterization and storyline, which I’ll detail later, I enjoyed the movie very much. A detailed discussion on the adaptation and the novel can be found at Ellen And Jim Have A Blog, Two (which I’ve avoided reading before I’ve written about it, but will read as soon as I post this). The screenplay proves to be more than just a streamlined version of the novel. It’s as if Davies and Yates tore the novel down to its core and reconstructed it, faithful for the most part but with substantial changes where it suited their purpose. I’ll limit myself on storyline changes except as they pertain to the variances in characterizations of three individuals that I want to highlight. These changes in character can appear minor but I think they deviate from Trollope’s book substantially and in one character the deviation contradicts the focus of the novel.

Felix Carbury: Matthew Macfadyen plays Felix in a wonderful portrayal that makes the cad likeable. There is nothing pleasant about Felix in the novel but Macfadyen plays on every sympathy possible, not just with the other characters but with the viewer, too. Felix’s lack of redemption, or if there is such a word his lack of redemptionability (spell-check tells me ‘no’), can be forgiven when you enjoy being around him. For the movie, Felix’s abduction to Europe leads to the same behavior on the continent (or maybe worse) than if he had stayed at home. The look on his face in the final scene, where he is practicing his card skills in a brothel, makes the perfect ending for someone that remains unperturbed by his changing circumstances or age.

Augustus Melmotte: David Suchet portrays a monster that is larger than life. Trollope makes clear that Melmotte’s humble origins continue to haunt him, his weak spots surfacing occasionally at inopportune moments. The screenplay suppresses any weak spot for Melmotte until his drunken stumble in the House of Commons. Part of the “problem” with Melmotte comes from Trollope’s resolution—the character clearly intended to face his problems “like a man” until the very last, then changes his mind when he takes his life. The movie has him recognizing suicide as an option much earlier, considering (and rejecting) the bottle of prussic acid as his problems surface.

The pivotal moment in the novel (to me) that indicates Melmotte has given up occurs when Marie tells her father that she will sign the papers to help save the family but he tells her it won’t be necessary. This adds another dimension to his subsequent behavior as well as relieves Marie of any guilt in his suicide. Yet that is not included in the movie. While the exclusion is consistent with Melmotte’s superhuman behavior of the movie, it undermines Trollope’s characterization. The screenplay turns Melmotte into a caricature, something that Trollope took care to avoid, showing his weaknesses and revealing some of his internal conflicts when it came to facing those shortcomings. The onscreen Melmotte (and many of the other characters) lack not just an inner life but development of it. Even so, Suchet plays what is handed him to perfection. While seeking to obtain status in England, the part Suchet highlights is his disdain for those around him. They aren’t worthy of him, yet he needs them for status, not to mention funds. A masterful performance, even if it doesn’t contain every dimension Trollope drew.

Paul Montague: Cillian Murphy (maybe best known to U.S. moviegoers for his roles in Batman Begins and Inception) plays the role given to him extremely well. Yet this is the change from the novel that I feel undermines much of what Trollope was trying to do with his novel. In the book, Trollope only intrudes a few times with direct observations but I believe they are a key to understanding his intent. Trollope makes it clear that people are frail, not always able to live up to society’s standards or their own beliefs because the necessary actions require a “hardness of heart”. That hardness requires an underlying concern for those you are dealing with.

In a novel where characters are making inner journeys, Paul has a long way to go. He is a moral weakling, knowing what he must do but remains unable to show that hardness of heart in order to do it. The Paul displayed in the movie proves to be a strong character, completely opposite from his written basis. The book Paul, while searching for the right thing to do regarding his directorship in the Mexican railroad, slowly distances himself from the Melmotte circle and seeks counsel from legitimate businessmen. The movie has Paul accepting the journey to Mexico where he works, hell-bent, on making the railroad legitimate (and the whole enterprise turns out to be legit?!?—where did that come from?). Upon returning to England, the movie Paul exposes Melmotte’s fraudulent plans. The book Paul did not have the strength to do this, probably even at the end.

All that being said, I highly recommend the movie as a good introduction to Trollope’s wonderful novel.