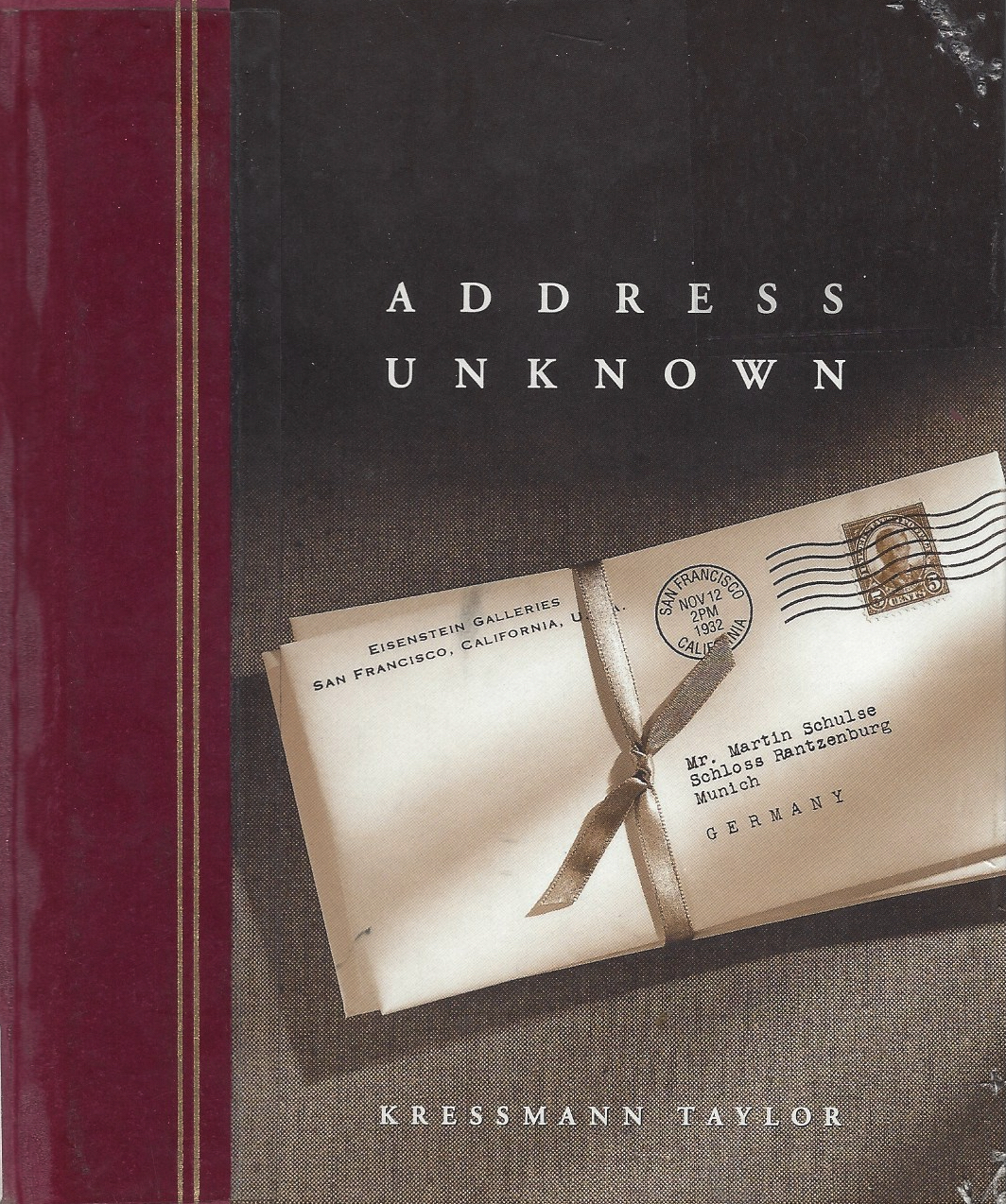

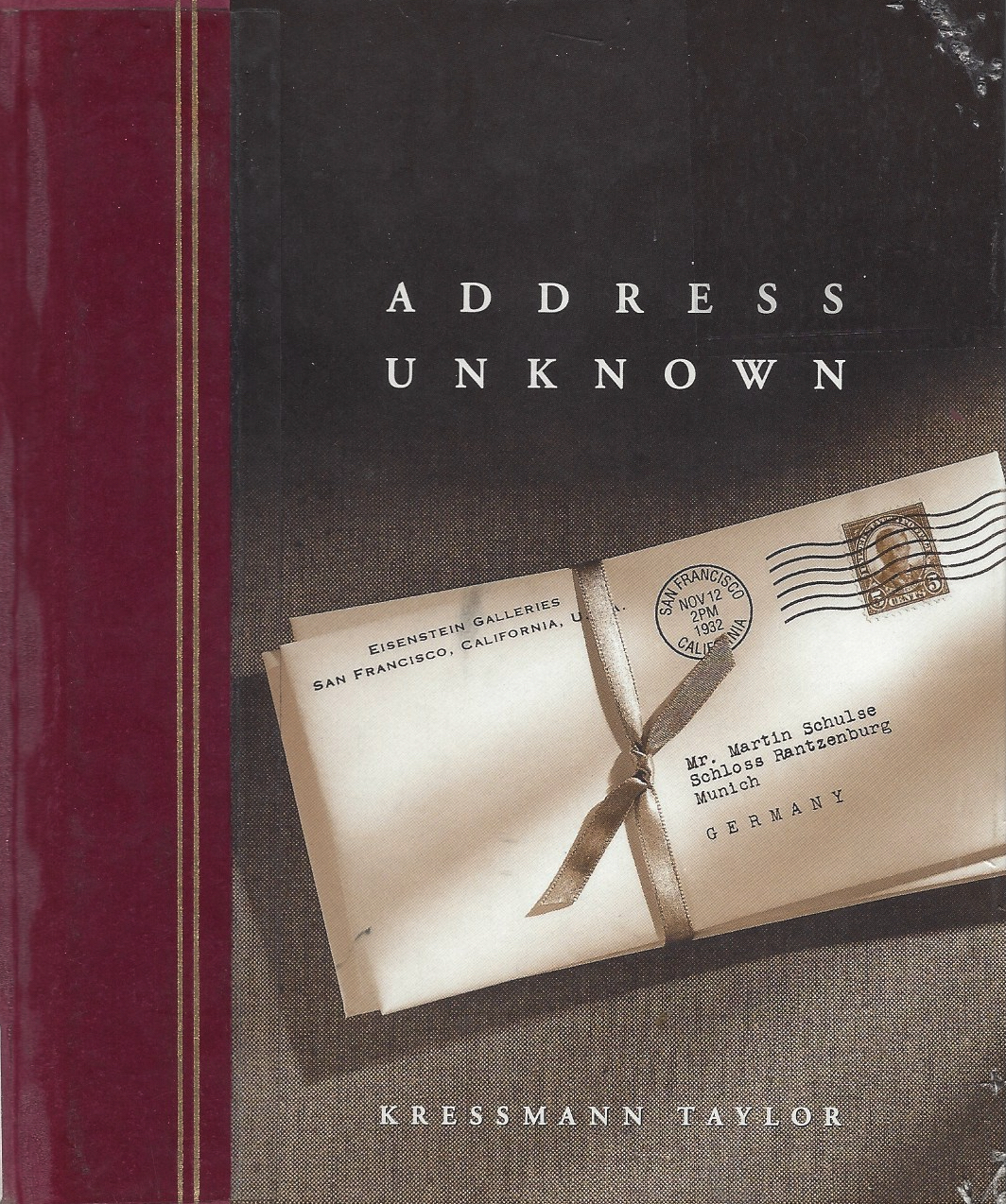

Address(ee) Unknown by Kathrine Kressmann Taylor

Another semi-recent article I should mention is Address Unknown: the great, forgotten anti-Nazi book everyone must read at The Guardian. There has been numerous blog reviews on the book over the years, and despite positive notes on the book I had never read it. The article title may be a bit overblown, but it did push me to finally read it. From the article:

Address Unknown was first published in Story magazine in September 1938, and then in book form a year later, becoming an instant bestseller. It has been translated across the world, adapted into a 1944 film and into multiple productions for the stage and radio – all under the name of Kressmann Taylor, after Story’s editor, along with Kathrine Kressmann Taylor’s husband, Elliott, decided it was “too strong to appear under the name of a woman”. The impact was immediate, the story credited with having “jolted America”, alerting it to the horror unfolding in Nazi Germany.

A short story-length tale, Address Unknown consists of the correspondence between business partners: Martin Schulse who has just returned to live with his family in Munich, Germany at the end of 1932, and (Jewish) Max Eisenstein who has stayed to run the U.S. business in San Francisco. As Max notes in his first letter, it’s been fourteen years since the end of The Great War: ” What a long way we have traveled, as peoples, from that bitterness!” As we know from history and soon find out in the story, maybe the distance isn’t as great as hoped. Martin describes how their business success affords him a privileged lifestyle in impoverished Germany. We also find out that Max’s sister Griselle, with whom Martin had an intense affair, has taken an acting role in a play in Vienna.

Martin brings up politics first, noting “there is much political unrest even now under the presidency of Hindenburg, a fine liberal whom I much admire.” Max asks about “this Adolf Hitler who seems rising toward power in Germany? I do not like what I read of him.” Martin responds,

I tell you truly, Max, I think in many ways Hitler is good for Germany, but I am not sure. He is now the active head of the government. I doubt much that even Hindenburg could now remove him from power, as he was truly forced to place him there. The man is like an electric shock, strong as only a great orator and a zealot can be. But I ask myself, is he quite sane? His brown shirt troops are of the rabble. They pillage and have started a bad Jewbaiting. But these may be minor things, the little surface scum when a big movement boils up. For I tell you, my friend, there is a surge — a surge. The people everywhere have had a quickening. You feel it in the streets and shops. The old despair has been thrown aside like a forgotten coat. No longer the people wrap themselves in shame; they hope again. Perhaps there may be found an end to this poverty. Something, I do not know what, will happen. A leader is found! Yet cautiously to myself I ask, a leader to where? Despair overthrown often turns us in mad directions.

The reader has to wonder how much of Martin’s thoughts were shared by his fellow Germans. Publicly he’s afraid to say anything, expressing no doubt, participating in local administration for his family’s benefit. Martin’s comments throughout highlight the clique-y nature and concerns of those lucky to be in the higher echelon of German society as the Nazis rise to power. Max’s analysis that Martin has a “liberal mind and warm heart [that] will tolerate no viciousness” seems to be on point, but Martin continues to play the necessary games in order to not just survive but thrive in the new regime. He’s caught up in the rebirth of Germany, both what is happening and what it symbolically means to Germans. His business acumen comes into play in regards to the politics, judging the positive benefits worth the negative cost.

The issue surrounding Max’s Jewishness is raised early, jokingly, in his comments about taking advantage of customers who expect certain behavior from Jews. It acquires greater meaning when his sister has to choose between new acting roles, one in Vienna and the other in Berlin. Max relays some of the horror stories he has heard from Jewish friends and their relatives in Germany. Here we see the beginning of a schism between the businessmen. Over the years they have been close friends as well as successful partners. Griselle’s Jewishness obviously wasn’t enough to keep her and Martin from having some sort of affair, although we’re not given a reason for things not going further between them. Martin’s dismissiveness of Max’s concerns is troubling. He diminishes what was happening in Germany as Jews simply being “the universal scapegoat,” which is fine as long as you’re not a Jew. Martin’s exhilaration in being part of a movement that is greater “than the men who make them up” paints him in a monstrous light to the modern reader, which may be one of the goals for Taylor.

Max’s concern for his friend/business partner and his sister are palpable in the subsequent letters. Toward Martin, he feels the pride in repatriation may not be as sincere as declared due to Martin’s fear of censorship. For his sister, Max’s concern of her being a high-profile Jew in Berlin appreciates when one of his letters to her is returned “Adressat Unbekannt,” addressee unknown. Max’s comment decocts what such a administrative, non-personal message means to those that receive it: “What a darkness those words carry! How can she be unknown? It is surely a message that she has come to harm. They know what has happened to her, those stamped letters say, but I am not to know. She has gone into some sort of void and it will be useless to seek her.”

I’ll end my notes on the letters at this point. The story is short and I highly recommend it if you have not read it. I will say that Taylor turns the irony meter off the dial in a manner she probably couldn’t fully foresee, but apparently had an impressive percipience. Her insights are what make the story so moving. I will add that most reviews focus on the rise of Nazism in Germany and Martin’s “conversion” in supporting it. What I found more interesting is Max’s behavior after the disappearance of his sister. In a sense, he mirrors the lacerated and aggrieved Germans Martin meets when he relocates. Finding pride…meaning…is fine, until you realize where that focus leads. What Max is willing to do, or rather what he knows will happen because of what he does, is every bit as monstrous as those he wishes to punish.

Links and Notes

- If you’d like to read the story, the text can be found here.

- Katherine Taylor’s papers are collected at Gettysburg College (where she taught). The guide to her papers includes an excellent biography.

- The library book I checked out was released in 1995, with a forward by then Story editor Lois Rosenthal.

Anonymous

By coincidence I just read a post on this story by Emma at her Book Around the Corner blog. It's a powerful plot: thanks for the link to the online edition – I just read it and was moved.

Dwight

You're welcome, and thanks for the note. Funny that she posted on it at the same time!

Emma

Very good post about this gem.

How insightful she was.

The building of the letters is extremely well done and we see the wall coming, us who know what happened after.

Nobody knows what they're capable of.

This is a huge consequence of WWII:the knowledge that everyone of us lives with a part of inhumanity, hidden somewhere.

I fully agree with you, Max and Martin both do something unthinkable, unbearable. Honestly, I don't know what I would have done in Max's shoes.

Emma

Dwight

Thanks Emma. I keep coming back to how perceptive Taylor was on some of the central questions of the time. For some people, it was evident if they attempted to understand what was going on. I'm reminded of the anecdote in Robert Caro's first book in his LBJ biography, The Path to Power when talking about how out of place Lady Bird Johnson was at Charles E. Marsh's mansion Longlea. Since LBJ treated his wife like crap, no one took her seriously. From Caro on page 491:

Had they been more observant, however, the Longlea regulars might have noticed qualities in the drab woman as well as in the elegant one [Marsh's lover Alice Glass, who may have been LBJ's mistress, too]. During the loud arguments to which she sat quietly listening, books would be mentioned; Lady Bird would, on her return to Washington, check those books out of the public library—check them out and read them. Because of Marsh’s preoccupation with Hitler, she checked out a copy of Mein Kampf, read it—and learned it. She never attempted to talk about it at Longlea, even though when Hitler’s theories were discussed thereafter, she was aware that, while marsh knew what he was talking about, no one else in the rood—except her.

Dwight

No one else in the room, that is.