Online reading: week of October 13

Picture source

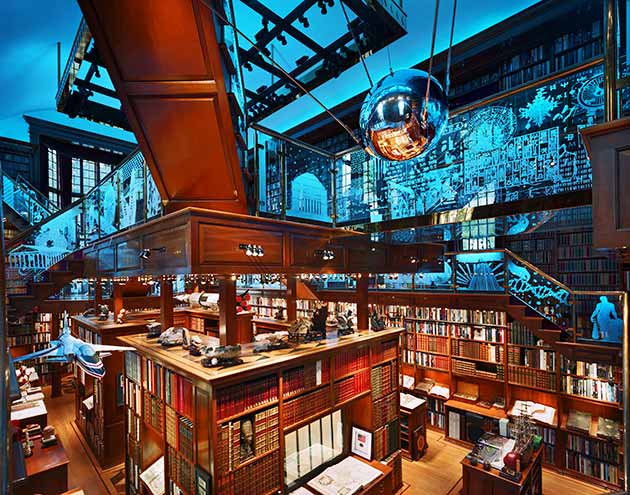

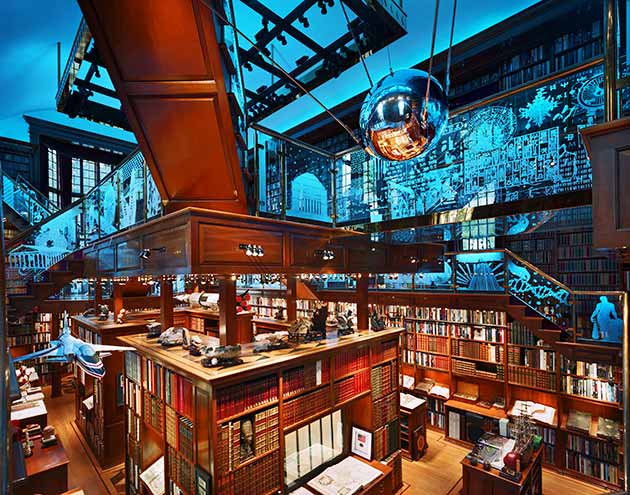

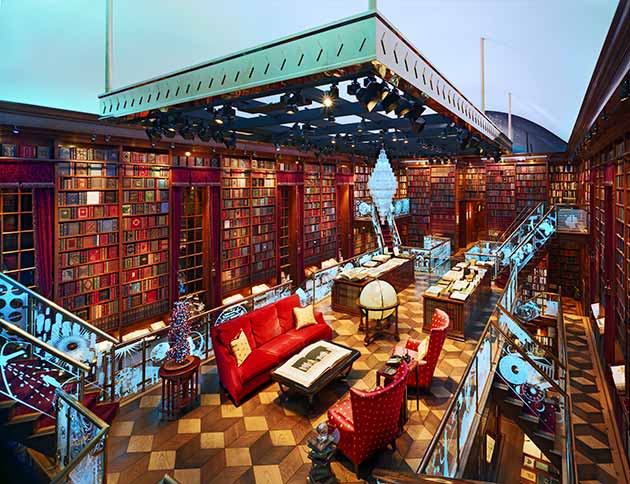

A few weeks ago I linked to an article featuring beautiful libraries. This article features Jay Walker’s library, “about 3,600 square feet on three mazelike levels”. The Escher-like library is a beauty to behold, as well as the interesting works it contains:

What gets him excited are things that changed the way people think, like Robert Hooke’s Micrographia. Published in 1665, it was the first book to contain illustrations made possible by the microscope. He’s also drawn to objects that embody a revelatory (or just plain weird) train of thought. “I get offered things that collectors don’t,” he says. “Nobody else would want a book on dwarfs, with pages beautifully hand-painted in silver and gold, but for me that makes perfect sense.”

What excites him even more is using his treasures to make mind-expanding connections. He loves juxtapositions, like placing a 16th-century map that combines experience and guesswork—”the first one showing North and South America,” he says—next to a modern map carried by astronauts to the moon. “If this is what can happen in 500 years, nothing is impossible.”

Do books make the man?

Speaking of libraries, Hitler’s Private Library: The Books That Shaped His Life is a look at influences in Hitler’s intellectual development. As the reviewer Robert Fulford mentions, this won’t explain everything (or maybe even much), but it does promise to provide some insights. From the product description:

Hitler’s education and worldview were formed largely from the books in his private library. Recently, hundreds of those books were discovered in the Library of Congress by Timothy Ryback, complete with Hitler’s marginalia on their pages—underlines, question marks, exclamation points, scrawled comments. Ryback traces the path of the key phrases and ideas that Hitler incorporated into his writing, speeches, conversations, self-definition, and actions.

We watch him embrace Don Quixote, Robinson Crusoe, and the works of Shakespeare. We see how an obscure treatise inspired his political career and a particular interpretation of Ibsen’s epic poem Peer Gynt helped mold his ruthless ambition. He admires Henry Ford’s anti-Semitic tract, The International Jew, and declares it required reading for fellow party members. We learn how his extensive readings on religion and the occult provide the blueprint for his notion of divine providence, how the words of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer are reborn as infamous Nazi catchphrases, and, finally, how a biography of Frederick the Great fired the destructive fanaticism that compelled Hitler to continue fighting World War II when all hope of victory was lost.

Articles on books/authors

A few articles I’m still working through about some authors I enjoy or need to read:

The Irish Prophet by Henrik Bering

On Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples by Michael Robertson

Revisiting Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan

Lastly, The Age of Wonder – How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science It is this story of the opposition between the Romantic poets and the science of their time that Richard Holmes sets out to undo.”

Building on a generation of revisionist scholarship that has been barely visible beyond the groves of academe, Holmes triumphantly shows that the Romantic age was one of symbiosis rather than opposition, in which scientists such as Sir Humphry Davy were also poets and poets such as Coleridge had a shaping influence on scientists – we discover indeed that it was Coleridge who was responsible for the early 19th-century invention of the term ‘scientist’ as an alternative to the older nomenclature ‘natural philosopher’.

Picture source