Copperhead: Harold Frederic (1893 novel) and 2013 Film (Ron Maxwell, director)

Earlier this year Amateur Reader posted on Harold Frederic’s The Damnation of Theron Ware, which reminded me of my reading of that novel as well as Frederic’s novella The Copperhead. At that time, the movie adaptation was available on Amazon Prime for only a few dollars, so I splurged and watched it. A few notes about both of them, although I’ll provide the caveat that it has been a while since I’ve read Frederic’s novella.

Frederic’s short stories about the U.S. Civil War have usually been published together, often including The Copperhead. Copperheads, for those unfamiliar with the term, were northern U.S. opponents to the Civil War. In the case of Frederic’s novella, the central character of Abner Beech is adamantly opposed to the Civil War, causing friction with the other residents of Four Corners in upstate New York. Jimmy, an orphan the Beeches have welcomed into their household, narrates how the abolitionist movement took hold in the area:

There was a certain dreamlike tricksiness of transformation in it all. At first there was only one Abolitionist, old “Jee” Hagadorn. Then, somehow, there came to be a number of them—and then, all at once, lo! everybody was an Abolitionist—that is to say, everybody but Abner Beech. The more general and enthusiastic the conversion of the others became, the more resolutely and doggedly he dug his heels into the ground, and braced his broad shoulders, and pulled in the opposite direction. The skies darkened, the wind rose, the storm of angry popular feeling burst swooping over the country-side, but Beech only stiffened his back and never budged an inch. (from Chapter 1)

Frederic, a native of Utica, makes upstate New York as much a character in many of his stories as the men and women populating them. On his writing of the U.S. Civil War, Frederic takes a very guarded position. There is no righteousness of the cause, there is no romanticism of war. Frederic focuses on the men, women, and children left at home during the fighting. In the novella, Frederic makes it difficult to like Abner Beech. Beech is against the war, mainly because he doesn’t think it worth spilling blood. He’s as racist as they come and doesn’t have a problem with slavery. Or at least he doesn’t think it an institution worth fighting over. If the southern states want to seceded, Abner says let them leave.

Edmund Wilson wrote an introduction to a reissue of The Civil War Stories of Harold Frederic and had this to say about these stories:

His [Frederic’s] stories of New York during the Civil War reflect the peculiar mixture of patriotism and disaffection which was characteristic of that region and for which [good friend Horatio] Seymour was so forthright a spokesman. Due to this, these stories differ fundamentally from any other Civil War fiction I know, and they have thus a unique historical as well as a literary importance. The hero of the longest of them—really a short novel—is not merely a critic of Republican policies but a real out-and-out Copperhead, an upstate farmer whose ideas are rooted in the principles of the American Revolution and who believes the South has the right to secede.

I recommend The Civil War Stories of Harold Frederic even though they don’t represent his best writing and are uneven. The best of them, The Copperhead included, focus on “the mixed feelings aroused by the war but also in their realistic footage focusing on the civilians at home.” (Wilson, again, in the introduction)

Abner was too intent upon his theme to notice. “Yes, peace!” he repeated, in the deep vibrating tones of his class-meeting manner. “Why, just think what’s been a-goin’ on! Great armies raised, hundreds of thousands of honest men taken from their work an’ set to murderin’ each other, whole deestricks of country torn up by the roots, homes desolated, the land filled with widows an’ orphans, an’ every house a house of mournin’.” (from Chapter 8)

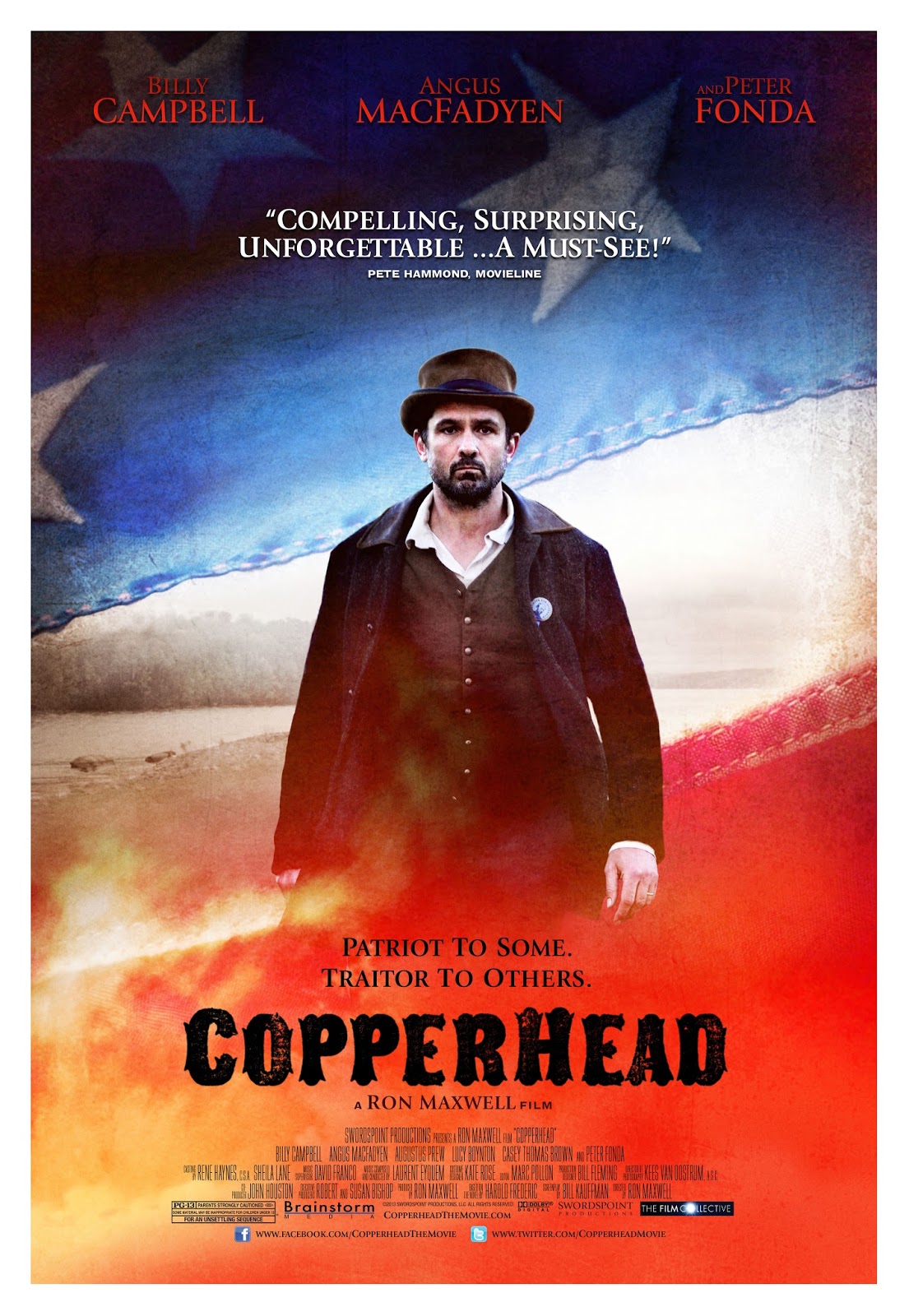

I thoroughly enjoyed the 2013 movie Copperhead directed by Ron Maxwell and adapted by Bill Kaufman. Minor changes made to the characters, Abner Beech in particular, improve the story. Abner, played perfectly by Billy Campbell, focuses more on his belief that the Constitution should guide the states’ and citizens’ actions, and he’s less than thrilled by the steps President Lincoln has taken. A major change to his character is that the movie Abner is very much anti-slavery, but he puts his dedication to the law over his hatred of slavery. There are other changes as well, and for the most part well done. If it’s possible, there’s an even stronger focus on the home front, as you see boys heading off to war and coming home, if they come home alive that is, irreparably changed.

The strength of the movie is its focus on the issue of community during wartime and the many divisive factors (political, religious, legal, familial, economic) that can tear it apart. If I had any complaints about the movie, it would be that the ending was even more heavy handed than Frederic’s. In such moments, though, it’s easy to see what Frederic was striving for. Men like Jee Hagadorn (played perfectly with scene-chewing aplomb by Angus Macfadyen) may be on the right side of this moral question, but at what cost in other areas? Fortunately the movie and the novella don’t pretend to make either Jee or Abner representative of the pro-war or anti-war North, instead using them to highlight important moral questions about this tumultuous period.

Highly recommended.