The Campaigns of Alexander: Book Six

The first topic occurs in the opening paragraph, where Alexander was planning to sail down the rivers feeding the Indus: “Since he intended to sail down the rivers to the Great Sea, he ordered the preparation of ships for that purpose. The ships were manned by the Phoenicians, Cyprians, Carians, and Egyptians who were accompanying the army.” (6.1.6, all quotes from The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander, translation by Pamela Mensch). Alexander had dismissed or left many men behind on his campaigns—why did he keep people known for naval expertise and shipbuilding skills? As pointed out in a footnote, “Arrian’s language here seems to imply that Alexander had brought naval crews with him into India, perhaps anticipating that he would eventually reach Ocean by marching eastward.”(Footnote 6.1.6b) This would be consistent with his speech to his officers after hearing of the troops’ discontent at the Hyphasis River (5.25.3-5.26). In that speech he claims he wants to “show the Macedonians and their allies” that he could sail from the Indian gulf to the Persian gulf all the way to the Pillars of Herakles, making the entire earth their empire as they do so. I found it interesting to see possible confirmation that these might have indeed been his plans.

As Alexander marches/sails down the rivers feeding the Indus it’s impossible to ignore the slaughtered bodies and razed cities in his wake. He knew he was leaving India, so what did he hope to accomplish with this carnage? Several local leaders he trusts enough to leave in charge end up revolting (much to their detriment), and Arrian points out a couple of times Alexander cannot find a local guide, hinting that the local population fears him too much to help him. In all this body count I also have to question Alexander’s targeting of Brahman holy men in the territory of the Malloi (6.7.4-6) and the slaughter of the Brahmans taking part in a revolt further down the Indus (6.16.5). Alexander has shown a high degree of religious tolerance to this point (and Arrian will point out more respect for Indian holy men in Book Seven) which makes these crackdowns stand out for their cruelty.

The punctured lung Alexander receives during the attack on a Malloi city receives a lot of attention in any write-up on Alexander and I’ll spend time with it, too, focusing on how his troops react. These are the same troops that cried tears of joy after Alexander concedes in their refusal to go any further than the Hyphasis River (at 5.29.1).

While Alexander remained there to be treated for his wound, the first report to reach the camp from which he had set out against the Malloi was that he had died of it. At first, as the news passed from one to another, the entire army raised a wail. But when they had ceased wailing, the troops grew disheartened and perplexed as to who would command the army, since a great many officers were held in equal esteem by both Alexander himself and the Macedonians … . (6.12.1-2)

Arrian stresses the troops’ concern on returning home safely since they were surrounded by hostile people and some of the so-called friendly people would revolt upon hearing of Alexander’s death. Upon seeing Alexander alive the troops “sent up a shout, some of them lifting their hands to the sky, others toward Alexander himself; many even wept in spite of themselves at the unhoped-for boon. (6.13.2) They were “disheartened and perplexed as to who would command the army” even though the officers are esteemed–it’s clear the men know none have the presence or ability of Alexander.

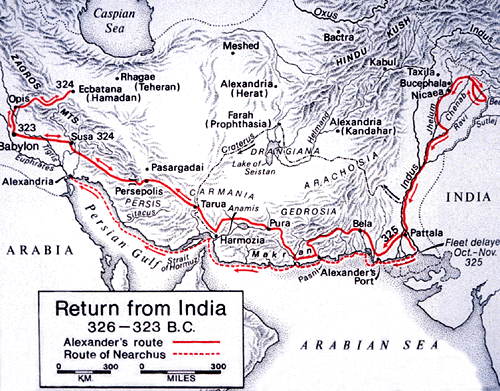

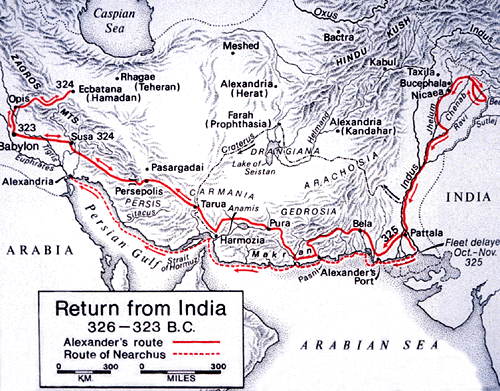

The march across the Gedrosian Desert also receives a lot of attention because of the brutal toll it takes on Alexander’s army. Often portrayed as Alexander’s revenge for his army’s refusal to continue the campaign, there are other considerations that are highlighted in footnotes to the text.

6.20.1a The improvements ordered at Patala [in the Indus River delta]… show that Alexander was planning to make this an important naval station, facilitating shipping and communications with the center of the empire. The land route into India, across the Indian Caucasus/Paropamisos (modern Hindu Kush), was arduous in summer and impossible in winter, so a sea route had to be develop if India was to be integrated with the other Asian territories. This goal does much to explain the otherwise irrational march through Gedrosia… .

…

6.20.4a Nearkhos’ ships, like most ancient sailing vessels, were not designed to carry large quantities of supplies, they were expected to put to shore each night to resupply themselves. Digging wells was thus the principal mission of Alexander’s land army during this march. Without them the fleet had no way to keep itself watered.

The march mentioned in the last note was a preliminary expedition before the main trek across the desert but fits in nicely with the picture of the troops headed through the desert, in part to provide short-term support for Nearkhos’ ships as well as establishing infrastructure for sea routes. Of course, that doesn’t mean Alexander wasn’t getting back at his troops but it does provide additional reasons for the arduous and costly journey. Another factor, which Arrian mentions here and Alexander mentions in his speech at the Opis revolt in Book Seven, is that no other army had crossed the desert. Accomplishing something that had never been done before seems to play no small part in Alexander’s motivations.