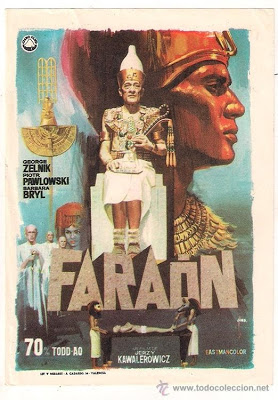

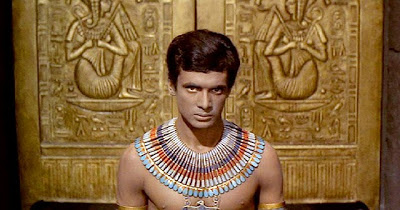

Faraon / Pharaoh (Film: Poland, 1966)

I’m going to post about a film before posting about the book for a change. Not that it matters…I’m not sure if it is harder to find the novel in the decent English translation or this film with English subtitles, but then I seem to excel in posting about things no one will ever read or see. And, as I normally recommend in these cases (for both the novel and the movie) I think they are well worth seeking out for reading/viewing.

Director Jerzy Kawalerowicz had his work cut out for him in adapting this novel to the screen—how to adapt what will look like a ‘sword and sandal’ epic but turns out to be a study in politics? Bolesław Prus’ novel looks at the dynamics of politics in Egypt during the eleventh century BCE using fictional rulers and characters. By looking at this fictional case, though, Prus was studying the dynamics in struggles for power of a state. The focus is on an Egypt in decline, bowing to local powers (militarily and/or financially) and those in power of the state. The priestly caste was responsible for Egypt having developed into a great power, but those days were past. Were the priests also responsible for its decline?

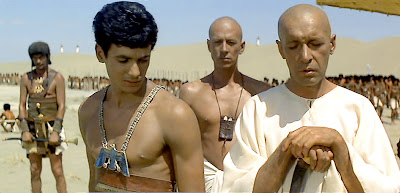

A long opening scene captures one aspect to that question: the Egyptian army is on the march but stopped in its tracks by two scarab beetles crossing the road. Instead of continuing on the road where sacred animals have crossed, the army is instructed by the accompanying priests to take a detour. This diversion causes the army to fill in a canal that a lone slave has worked on for a decade in order to free himself and his family from bondage. It turns out the army is on a drill, testing the prince Ramses XIII to see if he is ready to assume responsibility for the army. Ramses makes it clear he has little respect for the current generation of priests, complaining that the state treasury is empty while religious coffers overflow. Even more embarrassing to him is the fact that the best soldiers are mercenaries from other countries (especially Libya). He compares the state of Egypt and its forces to that of his great-grandfather, finding the current day lacking in every way. In every way other than priestly avarice, that is, which he declares to be the reason for Egypt’s decline. There are several haunting images in the opening scenes: the worker hanging from the intended canal waterworks, a sacrificial horse punctured with spears, and Ramses’ domination of a woman watching the procession go by.

Ramses complains to his father (the Pharaoh) about the priests being in charge of the country. His father declares he is really in control since he acts through Osiris. Ramses disagrees, pointing out that he believes the priests act on their own behalf instead of for the Pharaoh or Egypt. Three additional elements for influencing state power are introduced at this point. The first element beings with the character of Sarah, Ramses’ Jewish mistress. Love interests become powerful tools. The second element lies in the need for money—the moneylenders influence behavior directly and indirectly. The third element could be categorized as either a generational tension or a power struggle: those in power (the older generation and the priests) develop the young (or others) to assume power but grudgingly cede control. One example shows Ramses’ father declaring he will crush his son if he doesn’t agree to the upcoming (and already decided) negotiations.

The movie shows a developed Ramses, at least as far as his moral consciousness. His concern for the people is real, as is his desire to make their life easier at the expense of not filling religious coffers. He still falls prey to the love interest angle, though. He has a son with Sarah but rejects her and his son when he finds it is predetermined that she will be sent home so his son will be a leader of the Jews. The priests use Kama, a Phoenician priestess, to successfully influence Ramses as they wish.

The moneylending angle is a little more difficult to follow in the movie but still important. Egypt and individuals borrow from several sources, the most common source being Phoenician merchants. In the world of realpolitik this gives them more influence on the Egyptians than the Assyrians would like to see. Assyria has amassed an army three times the size of the Egyptian forces and has been withholding its tribute to the Pharaoh’s coffers. Where the priests and Pharaoh see a need for a treaty with Assyria, which little benefits Egypt other than providing a subservient peace, Ramses sees an insult. His struggle for power within Egypt against his father and the priests as well as his intentions against the Assyrians for regional supremacy provides the core of the story, which Kawalerowicz captures very well. The other area that receives emphasis is the differences between the classes. The rulers have an orgy while the dismissed Libyan mercenaries burn and pillage. The workers toil seven days a week in order to provide the elites with their luxuries.

Pentuer (a priest): “Cheop’s tomb claimed half a million lives and how many tears, how much blood and pain?”

Ramses: “What matters is not whether the pyramids were necessary, but that obedience to Pharaoh’s will. Yes, Pentuer, the pyramid is not Cheop’s tomb, it is Cheop’s will.”

Pentuer: “Would you also like to prove your power this way, my Lord?”

Ramses: “How come you, a priest, are well disposed to me?”

Pentuer: “The gods warned me that you, if such is your will, could extricate the Egyptian people from poverty.”

Ramses: “What do you care about the people?”

Pentuer: “I originated from the people. My father and my brother would draw water from the Nile and would be cudgeled.”

Ramses: “How can I help the people?”

Pentuer: “The people work too hard. They pay too many taxes. They suffer poverty and persecution.”

Ramses: “Peasants, always peasants. For you, priest, only someone eaten by lice deserves pity. Why don’t you count the Pharaohs who were dying in pain, who were murdered? But you don’t remember them. Death is no more generous with me than with your peasant.”

Pentuer: (hearing the people chant prayers) “Why are they praying at this time?”

Ramses: “You’d better tell me why they are praying at all when nobody can hear them.”

The power struggle between Ramses and the priests brings many of these themes together. Ramses wants to supplant the priests, ruling on his own without their influence. He seeks to wage war with Assyria in order to become the regional power Egypt used to be (in this the machinations of Phoenician moneylenders help and manipulate him). Ramses also wants to improve the lot of the commoners. In order to accomplish these goals Ramses has won over the army with his leadership style. He also deals with the Phoenicians in order to finance some of these goals, but he seeks control of the vast treasury held deep in a labyrinth (to which the priests control access). Ramses fails for several reasons, mostly because of the strength of the priestly class but also from his personal failings. The religion of the people play a crucial role, too, while Ramses is ignorant of celestial events the priests knew were going to happen. Interestingly enough, Jerzy Zelnik plays both Ramses and the Greek sent by the priests to assassinate him, highlighting a duality or split within the young Pharaoh that has been emphasized at other times. My only real complaint with the movie would be that it ends with the death of Ramses and doesn’t show the novel’s ending, which has the successor Herhor (a priest) carry out many of the reforms Ramses started. The movie clocks in at three hours as it is, so I guess Ramses’ death and failure provides a good stopping point. The movie contains much of the same pessimism as the novel, although without the eventual reforms the message seems even more bleak.

There are several long shots in the movie, taking up plenty of time to establish what seems like narrow points. I found them effective, though, and well done. The English subtitles were poor, often with many misspellings. I watched the VHS tape copyrighted 1998 by Polart.com, which I’ve cut some slack in the past for its poor subtitles because they are the only source with English translations for many Polish films I’ve watched, usually based on Polish novels. This was a particularly poor job, though. Looking for stills of the movie I was surprised to see how much richer the colors were in the photos versus the washed out feel of the print I watched. This movie (and the novel it’s based on) deserves a much wider audience in translation with an improved print and translation.

Brian Joseph

Indeed you have found a film that many will never see! Based on your commentary as well as information over at the IMDB this sounds like a seriously good effort.

As for the quality of your copy I wish that we lived in a world where all old moves were digitized in their most pristine form.

Dwight

There were only 8 copies of this movie(with English subtitles) listed on WorldCat. Several of those don't lend audiovisual material so I was lucky to get a copy. Thank you Divine Word College in Iowa!

There are more copies of the version of the book available on WorldCat but this is a novel that deserves a wider audience, which I hope to provide a start when I post on it in a few weeks!

Sidenote: do NOT get the version translated by Jeremiah Curtain, often going by the title "The Pharaoh and the Priest"…it's incomplete and supposedly a very bad translation)