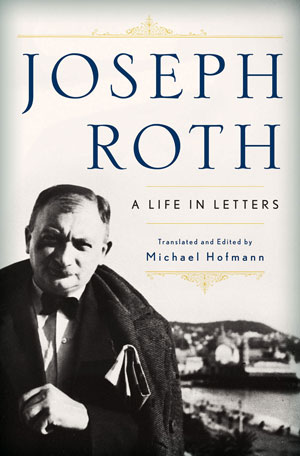

Joseph Roth: A Life in Letters: 1911 – 1924

I finally had some time to start Joseph Roth: A Life in Letters, translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. The young Roth sounds so…so…young, something that doesn’t come through in any of his work I’ve read so far. I’ll quote from some of his letters as they strike me, even if they are as inconsequential as what follows.

This letter struck me because I couldn’t help but compare it to the Trotta’s Sunday lunch in The Radetzky March. From letter no. 6, to his cousin Paula Grübel (1916, Vienna):

There is something of Venice in the air today, as there sometimes is on summer days, and I am in a mood as if after lunch I were going by gondola to some wharf. … I am going to have my lunch soon, and am looking forward to it. Today we are having something cheesy and prosy, but the Venetian element in the air today will ennoble and Italianize it, and I will eat nothing cheesy or prosy, but macaroni. And then I really will go out on a gondola, past the Ring and the Volkgarten, and I will encounter a pretty Venetian girl, and will accost her thus: May I bore you, Signorina? And the pretty Venetian girl will reply in purest Viennese: See if I care. And for all that, I am in Venice today. Today, today only, I am the doge of Venice and an Italian tramp rolled in one, but tomorrow, tomorrow I will go back to being the dreamy German poet, art enthusiast, and 3rd year German student studying under Professor Brecht. …

Lunch wasn’t good, because firstly, my neighbor beat his wife with a broomstick. Secondly, the macaroni weren’t proper macaroni at all. And thirdly, Auntie Rieke ate cheese off the point of her knife. Just as well Aunt Mina confiscated my revolver in Lemberg, otherwise I might have committed tanticide.

A few more quotes from the young Roth’s letters:

From letter no. 5, also to Paula (1915 or 1916); ironic given his later experience (both in doing what he says he would and what he wouldn’t):

What do you think about money? I don’t think it’s worth bothering about. If I had it, I would chuck it out the window. Money’s the opposite of women. You think highly of a woman until you’ve got her, then when you get her, you feel like chucking her out (or at least you ought). Whereas money you despise as long as you don’t have it, and then you think very highly of it.

Also from letter no. 6:

The fair-haired boy, the dog, and I—we are the only decent people in the whole building.

From letter no. 7, again to his cousin Paula, this time from his field post during World War I (24 August 1917). Again, ideas from The Radetzky March appear as well as some beautiful lines:

I am currently in some Augean shtetl in East Galicia. Gray filth, harboring one or two Jewish businesses. Everything’s awash when it rains, and when the sun comes out it starts to stink. But the location has one great advantage: it’s about 6 miles behind the lines. Reserve encampment.

Materially, I’m not so well off as I used to be. Our newspaper is failing, and once the aura of reporter has faded away, there’ll be nothing left of me but a one-year volunteer. And I’ll be treated accordingly.

But for the likes of me that doesn’t really matter. The main thing is experience, intensity of feeling, tunneling into events. I have experienced frightful moments of grim beauty. Little opportunity for active creation, aside from a couple of lyric poems, which were more out of passive sensation anyway.