Kozma: A Tragedy by Mihály Kornis

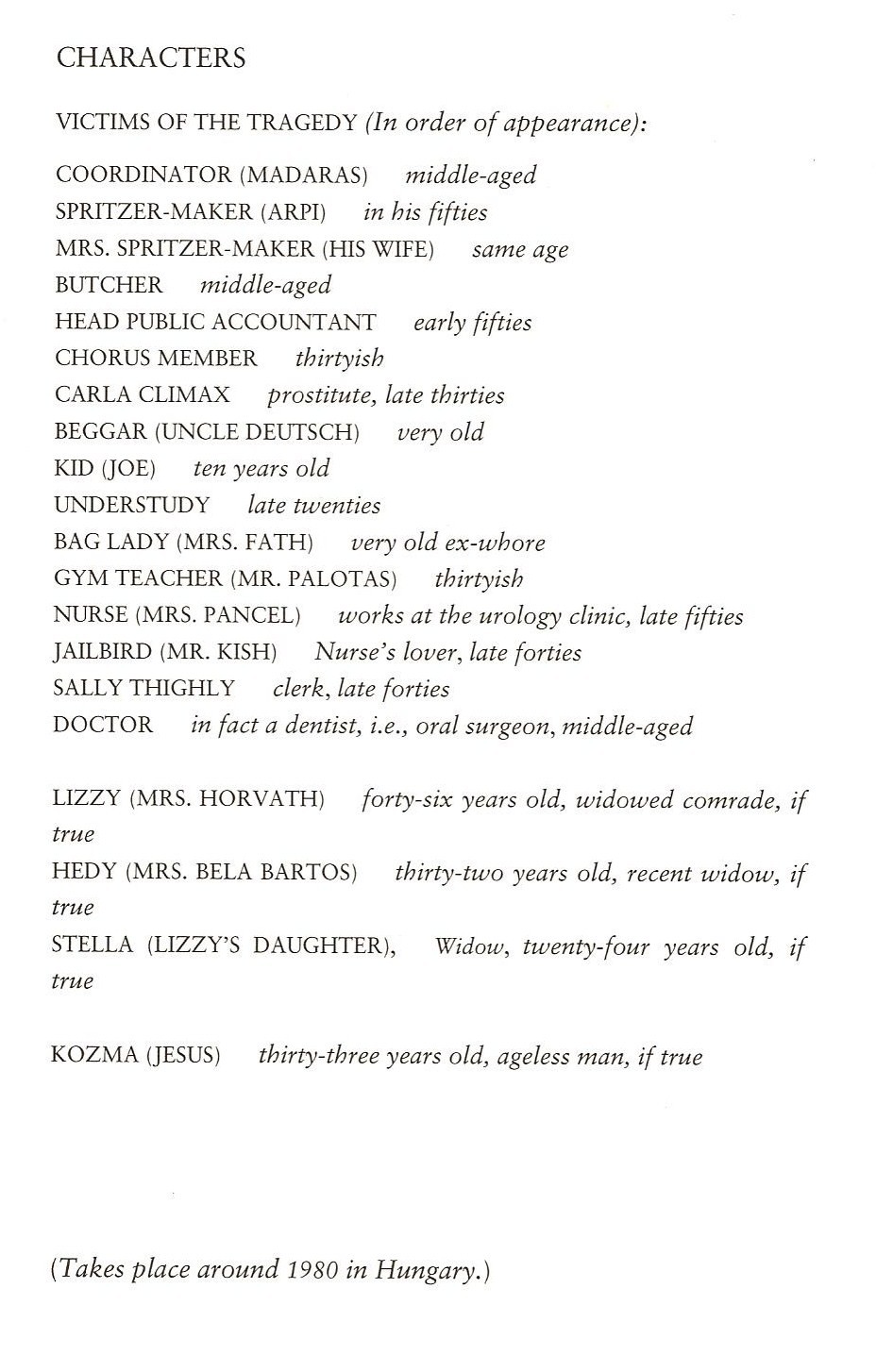

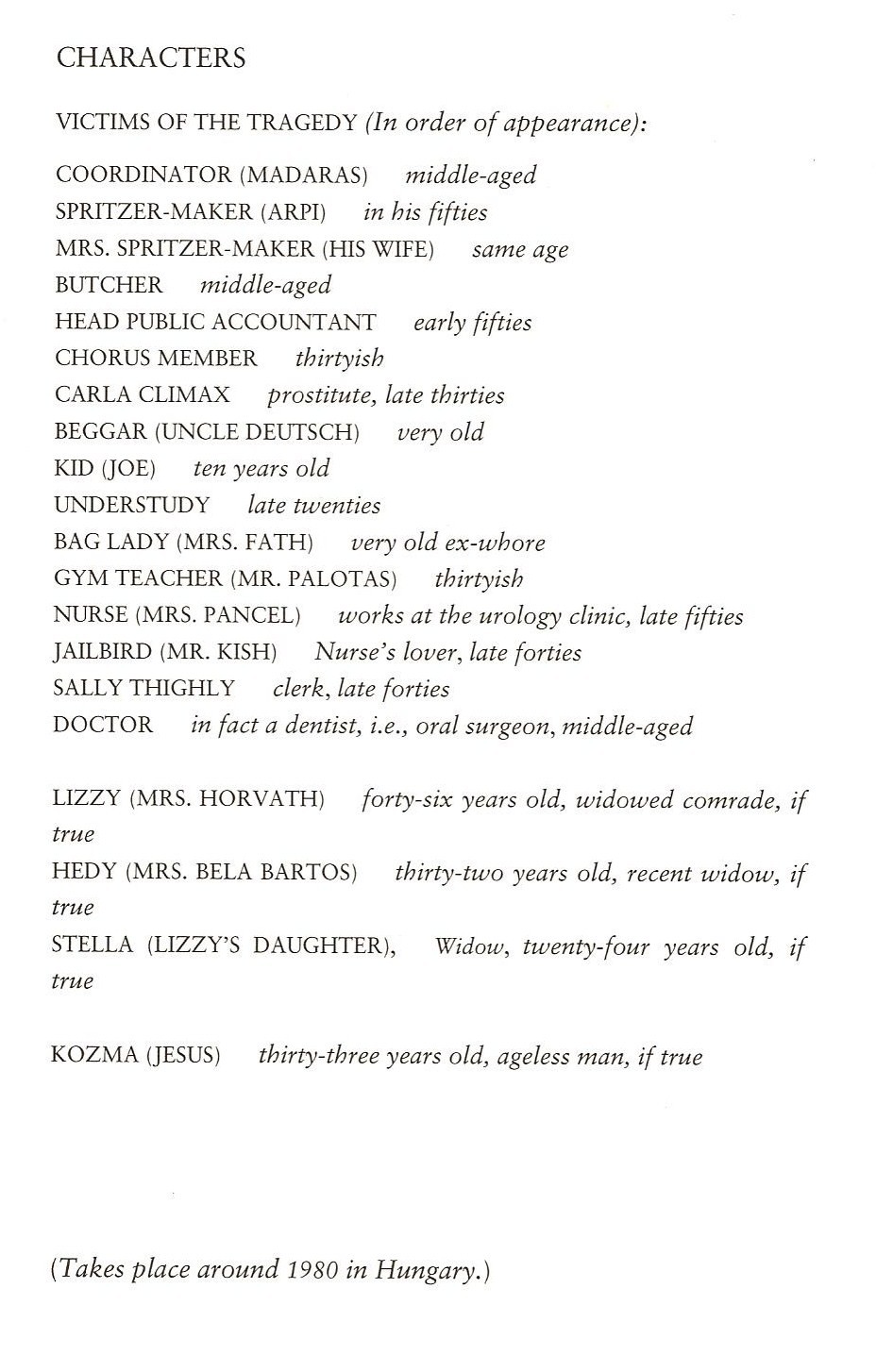

Character list for “Kozma: A Tragedy” by Mihály Kornis

A Mirror to the Cage: Three Contemporary Hungarian Plays

Edited and Translated by Clara Györgyey

Introduction by Ervin C. Brody

Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 1993

ISBN 1557282676

The final play in A Mirror to the Cage: Three Contemporary Hungarian Play, Mihály Kornis’ “Kozma: A Tragedy” certainly is the strangest, which is saying a lot. Take a look at the character list and you’ll notice “if true” appears for the four central characters. The description of the setting highlights the impossibility of the play that follows:

Scene: Enclosed resort on the shore of Lake Balaton. On the horizon the glittering, sun-drenched, sandy beach edges the fleecy blue sky. The spawning plateau is sealed by a ten-foot-high brick wall surmounted by a barbed-wire fence. Further back, in center stage, a rickety military truck (turned into a bus for transporting people), is idling; its wheels are spinning helplessly in the dust without moving even an inch. On the scattered metal benches fifteen to twenty people are sitting in strangely differing outfits: winter, summer, even night clothes; some are wearing overalls, some pajamas and dressing gowns, while other wear heavy winter coats. They appear to have been transported without having had time to change. The struggling of the incapacitated truck makes a deafening rattle.

In the foreground, three women are sunbathing, naked, on air mattresses formed into chaise lounges; their eyes are closed, one of them is sporting a small, glowing leaf on her nose. Each woman is in the prime of her age group, although the youngest wears thick eyeglasses. Beside them, under a beach umbrella, ice buckets and coolers, filled with a wide assortment of cheap and very expensive drinks, are visible, along with crystal and plastic glasses, creams, lotions, and other cosmetic paraphernalia, in garish taste. The ladies seem unperturbed by the ear-splitting noise; to them it sounds as natural as the blowing of the wind. Completely relaxed, they are basking with their limbs spread.

The whole scene is extremely improbable. The place is enclosed almost hermetically, no truck could ever get in; there is only a narrow, graveled path leading offstage on the left. The heat is sweltering. (190)

The term “Kafkaesque” is overused, but I think it fits here in the sense that if you accept one outlandish premise at the start of the story—if a man can wake up as a giant insect, or a bus-load of apparitions miraculously appears in a sealed-off resort—everything that follows unfolds in a logical and sensible manner, no matter how bizarre. The truckload of people are noted as “victims of the tragedy.” What tragedy? How can they die and return to life? How come the living can’t see them but feel their presence? Are they who they claim to be? What committee does the Coordinator mean will investigate what has happened? Nothing is explained, although there are several possibilities.

The resort, modeled on an artists’ retreat to reward loyalty or entice new talent, is beautiful only on the outside, built (or at least implied) on the bodies of the common people represented on the bus. The three women sunbathing are the protagonists: Lizzy, Hedy, and Lizzy’s daughter Stella. Lizzy and Hedy, widows of Secret Police officers, reminisce about their lives. Their lies about the past gradually unravel and their nasty natures are revealed. Stella, a spoiled girl who has moved to Berlin, represents the worst sides of her mother and the West. The busdriver, Kozma, suddenly appears and helps unmask the sordid nature of these women—they assisted in their husbands’ deaths in order to live the life of luxury a hero’s widow earned. They each see their dead husband in Kozma, confessing everything to him. Instead of a “happily ever after” ending though, the women kill Kozma and apparently themselves. The dead passengers are resurrected and try to return home, only to realize they are stuck in place forever—there is no justice or resolution for them. The passengers and Kozma will always be victims, doomed to eternally suffer from treachery encouraged by the system where “only whores survive.”

Each of the three plays in A Mirror to the Cage: Three Contemporary Hungarian Plays has varying degrees of success in transcending their setting and move beyond a narrow, political focus. Örkény’s “Stevie in the Bloodbath” highlights the absurdity in life that results from our ability to “stand on either side of the barricades at the same time and in the same person.” Spiró’s “The Imposter,” the most successful in expanding beyond a narrow focus, uses an early 19th-century setting and the performance of Tartuffe to highlight how the human condition doesn’t change but external conditions may corrupt people and art. Kornis’ “Kozma” seems to be the least successful in moving beyond its setting but the alienation and guilt within that setting, without any hope of deliverance or justice, still provides a powerful message. It also reinforces the message that human nature will react to incentives, no matter how perverse or evil.

Links related to Mihály Kornis at Hungarian Literature Online:

Brian Joseph

Sounds very interesting and thought provoking. Weather Kafaesque or just absurdist, all things being equal I tend to like stories like this. Realism is fine but that I like a nice change of pace if presented intelligently.

Dwight

You would definitely like this collection. My only issue on these, which I hope I conveyed, is how well they transcend the narrow period they cover. I think they did well in general, some better than others.