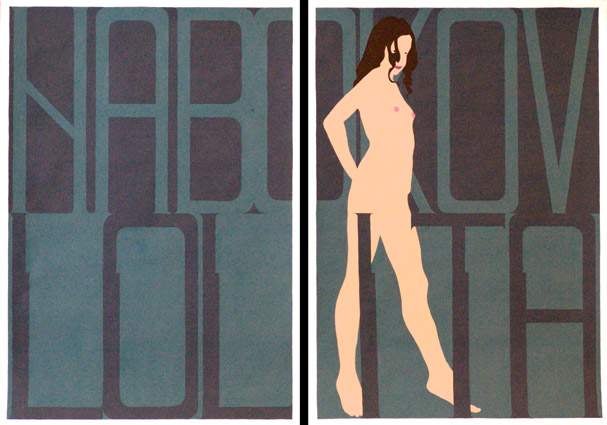

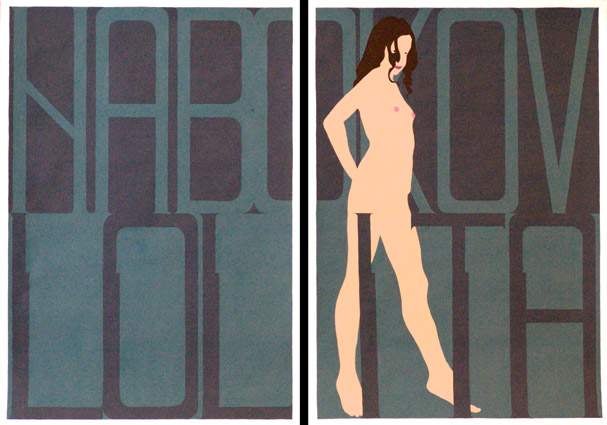

Lolita discussion: Part One, Chapters 1 – 17

So Humbert the Cubus schemed and dreamed—and the red sun of desire and decision (the two things that create a live world) rose higher and higher, while upon a succession of balconies a succession of libertines, sparkling glass in hand, toasted the bliss of past and future nights. Then, figuratively speaking, I shattered the glass and boldly imagined (for I was drunk on those visions by then and underrated the gentleness of my nature) how eventually I might blackmail—no, that is too strong a word—mauvemail big Haze into letting me consort with little Haze by gently threatening the poor doting Big Dove with desertion if she tried to bar me from playing with my legal stepdaughter. In a word, before such an Amazing Offer, before such a vastness and variety of vistas, I was as helpless as Adam at the preview of early oriental history, mirage in his apple orchard.

From Part One, Chapter 17

Delicious. Lolita is a joy to read…to hear… while the subject matter is disturbing. The narrator’s seductive language pulls the reader into his world, deeper into his mind. Which is clearly the intent. Humbert Humbert, the narrator (HH), shapes his tale as a justification of his actions. HH addresses his imagined jury so the reader knows that things will be skewed in his favor even as he claims perfect memory and impartial presentation. His claim at times that “the artist in me” takes “the upper hand over the gentleman” fails on several counts—while not a gentleman, the artist characterization raises doubt as to how truthful is his portrayal of events. Compounding the reliability question is Dr. Ray’s Forward to the book. The reader can feel twice removed from what actually happened, even if the doctor’s claim that only a few names have been changed. A seed of doubt as to other changes have been planted with the doctor’s wish to make the book both a classic and a cautionary tale.

While the techniques used by Nabokov are fun to read, do they really advance the story? Or to put it another way, Nabokov parodies many things but does the book rise above simple parody? Is there substance beyond the puzzles? It is too early for me to make a judgment since I know hints are being left for future events. Many of the devices seem to be used simply for their own sake. But then that is part of the appeal. Trying to figure out all of the puzzles presented is part of the overall game, including which ones are relevant and which ones are meant to misdirect. In the course of a few pages I noted Nabokov’s use of the following motifs, techniques, devices, etc.:

- Literary references (Poe is a major one—fitting given the crime novel aspect of the book)

- Time and memory (Proust is explicitly mentioned)

- Metamorphoses (many things developing: Lolita, butterfly references, etc.)

- Coincidence (fate plays a major role)

- The number 3 (and other numbers will reappear, like 342)

- The inadequacy of words (“I only have words to play with!”)

- Anagrams

- Contrasts (black/white, light/shade)

- Wordplay (see opening quote for some fun examples)

- Unreliability of narrator (bouts of insanity are confessed)

- Unreliability of experts (psychiatry is a favorite target)

Again, this is just a sample from a few pages. HH also uses different styles of presenting the information such as inserting journal entries (accurately recalled, allegedly, since the original was destroyed—did I mention a reliability factor?) or lists to push the story along. The self-confession is a particularly effective method for this story. HH constantly paints himself as a predator, apparently not skimping on details that paint himself in a bad light in order to add believability. He draws the reader into his confidence, but his self-justifications jolt back to reality—this is a very sick person.

This section covers up to the point where HH is given an ultimatum by Charlotte Haze—marry me or move out of the house. The reader sees Humbert’s dysfunction develop (mature isn’t quite the right word). The pleasure in reading this so far (to me) has been in the techniques, not the story. There are several devices and motifs that are enjoyable to watch unfolding. A major pattern involves the numerous use of doubles. Annabel has a double in Dolores. HH’s ‘love’ for Dolores has its double or mimicry in her mother’s ‘love’ of HH. Even the words have double meaning or evoke other meanings. Words frequently call forth Dolores’ name (dolor, dolorous) or the last name of Haze “chosen” for the book by Dr. Ray (hazy is an often-used descriptor). With all the doubles or echoes in the book, I don’t find it coincidental that the object of his “affection” has more than one name.

I’m about two months removed from having read this so this discussion will be brief, but I’ll add a couple of other notes. In HH’s defense, he likes to paint himself the victim…whether it is a victim of “arbitrary” rules (it is OK to court a 16 year old girl but not one of 12), of coincidence (which pile up fast), or even of Dolores herself. HH claims his actions are chaste since he has taken nothing from her or done nothing to her, alerting the reader that he is too far gone in his reveries to consider why his actions aren’t OK. Little details lend richness and additional meanings to scenes, Dolores eating an apple during the famous couch scene (Chapter 13) for example. There is an innocence lost during the incident, but the fruit does not yield understanding (or the ability to differentiate between good and evil) for HH.

Hopefully I’ll be able to find some time to finish the book and write up the discussions so I can fully concentrate on Shakespeare and Spenser. I didn’t intend to get stuck in the 16th century, but that’s where McFate is taking me…

Emily Barton

Wonderful, wonderful, thoughtful analysis here. That paragraph you chose to quote reminds me of how extremely clever Nabokov was with words and makes me want to read him again. I like the way this book had parody within parody within parody (like a Russian doll). Looking forward to seeing what you have to say once you finish it.