The Peloponnesian War: Syracuse and chances lost (6:63-105)

Picture source

And the Syracusian horsemen, which were ever abroad for scouts, spurring up to the camp of the Athenians, amongst other scorns asked them, whether they came not rather to dwell in the land of another than to restore the Leontines to their own.

(Book Six, Chapter 63)

This post looks at Chapters 63 through 105 of Book Six, covering the activities of the winter of 415/4 BC and most of the subsequent summer. All quotes (and spellings) come from the Thomas Hobbes translation.

During that winter the Athenians defer carrying out any direct operation against the Syracusians, who gather courage from the delay. The Athenians, wishing to establish a base near Syracuse but unable to do so with the Syracusian cavalry present, use a double agent to create a ruse, luring the Syracusian army and cavalry away from the city. The absence of an Athenian cavalry looms large throughout the battle and siege of Syracuse, focusing additional blame on Nicias. During his bluff to the Athenian council, he had said the cavalry of Syracuse would provide the enemy with an advantage that Athens could not counter given the limited resources originally granted. Yet when asked to update what the Athenians would need, Nicias did not ask for any cavalry. He said Egesta could provide the Athenians with a cavalry unit, either forgetting his advice that the Egestaeans should not be trusted or not believing the expedition would go forward given his exorbitant demands.

With the Syracusian army and cavalry out of the city, the Athenians establish and fortify a favorable position near Syracuse. When the Syracusians return, they prepare for battle just outside their city. Thucydides provides each side’s motivation: “And they came on to fight, the Syracusians for their country and their lives for the present, and for their liberty in the future: on the other side, the Athenians to win the country of another and make it their own, and not to weaken their own by being vanquished.” I had to step back here for a minute and wonder why Athens was directly attacking Syracuse. This had not been part of their original plan. After finding out the Egestaeans had fooled them about their wealth, Lamachus had proposed sailing directly into Syracuse and taking the city by surprise, but he eventually changed his mind and supported Alcibiades’ plan to attract allies on the island before attacking Selinus and Syracuse. With Alcibiades gone, the Athenians were being led by Lamachus and Nicias (who just wanted to sail home). The fleet had wasted most of the summer trying to find allies on the island, but the size of their fleet scared most Sicilian cities from receiving them. Given all these handicaps, the Athenians almost carry the day at this battle (called the battle of the Anapus River). A complete rout is averted only because the Syracusian cavalry is able to protect the soldiers as they retreated to the city.

Instead of taking advantage of this victory and pressing forward, Nicias and Lamachus take the Athenian army back to Catana for the winter and send to Athens for money and horsemen. Similar examples of tactical competence during a battle but strategic blindspots in the overall campaign would dog the expedition. This delay allows Syracuse to rebuild their army and request aid from Sparta and Corinth. The Athenians attempt to take Messana, one of the initial goals, but get a taste of Alcibiades’ traitorous nature. When fleeing from the Athenians, Alcibiades found out about the plot to deliver Messana to the Athenians and has the appropriate leaders warned. The plot falls apart and the Athenians fail in their siege of Messana.

The Syracusians take advantage of the Athenians not directly pressuring the city to extend the city walls for greater protection. Finding out that the Athenians were sending ambassadors to Camarina, Hermocrates goes to their assembly to warn of Athens’ true intentions, or at least as he saw it. Hermocrates cautions the assembly that the Athenians wish to subjugate all of Sicily, city by city, just as they did in Greece. He reminds them of his call for a united Sicilian front. He also warns Camarina that if they join Athens and are victorious over Syracuse, Camarina will soon have to defend itself against Athens. Neutrality will not change the equation. He reassures them there is no reason to be afraid since the Syracusians have held off Athens to this point, not to mention Peloponnesian help was on the way.

Euphemus of Athens responded by framing Athens as building an Ionian defense against an aggressive Dorian alliance. He admits that Athens assumed command of the cities in the Delian League but that was because many within the league had joined the side of the Persians when Athens was invaded. Euphemus paints Athens as the protector of freedom for Sicily. He acknowledges Athens’ benefit from their alliances and choosing their friendships based on the usefulness of the ally. He reminds them that the constant threat would always be the nearest power, which is Sicily. Euphemus tries to paint Athens’ interest as strictly defensive and in the interest of free Greeks everywhere.

What can Camarina do? They are convinced that Athens means to subjugate Sicily. Syracuse was constantly harassing them over border disputes. While they declared neutrality, they secretly sent help to Syracuse because they were the closer, immediate threat. In addition, Camarina thought Syracuse just might win against Athens, the delay of Nicias and Lamachus after their victory on the field haunting Athens already. Athens’ strategy of directly attacking Syracuse, probably rationalized as treating the source of the problems on the island (at least with Athens’ allies), lends credence to charges of desiring complete Sicilian subjugation.

During the winter the Athenians build up supplies necessary for a siege and send for help from Carthage (?!?). The ambassadors sent from Syracuse to the Peloponnesus receive enthusiastic support from Corinth. When the ambassadors arrive in Sparta, Alcibiades happens to be there and speaks to the assembly. He defends his actions in Athens, saying he had to work within the democracy but was able to tame the more headstrong impulses of the people. He says he believes the democracy was ludicrous but that was the government Athens inherited. Also, there was no way the people were going to change the government while tensions existed with Sparta. Alcibiades then claims that the Athenians had come “first (if we could) to subdue the Sicilians; after them the Italians; after them, to assay the dominion of Carthage, and Carthage itself.” Invasion of the Peloponnesus would be next if these goals, or most of them, were successful. In addition to encouraging the Spartans to send a commander to lead the Syracusians (and as many troops as they can spare), he urges them to “likewise fortify Deceleia in the territory of Athens, a thing which the Athenians themselves most fear”. He claims he cannot be called a traitor because Athens betrayed him first, and a true patriot will do what he must to recover his country, even if it means aligning with enemies. He reiterates that he can “help you much when I am your friend” and counsels them to “pull down the power of the Athenians both present and to come”.

Alcibiades had to provide a masterful sales pitch if the Spartans were to believe him. One point where he could have been called on dealt with the Athenian plans and his claim that “the generals there [in Sicily], as far as they can, will also [still] put into execution.” Given Nicias’ reputation (in the previous post Hermocrates knew “the man of most experience amongst their [Athenian] commanders hath the charge against his will; and would take a light occasion to return”), could the Spartans believe such a claim? Apparently they gave some credence to his speech but weighted their actions toward what they already wanted to do. Sparta prepared to send troops to fortify Deceleia in Attica but for Syracuse they agreed only to provide Gylippus as chief commander. The Spartans prove the Corinthians (Book One, Chapter 70) partially right in their willingness not to engage beyond what they believed necessary, but the plans for the fortification at Deceleia is a major departure…more on that in future posts when it comes into play. In the meantime, the Athenians grant Nicias’ and Lamachus’ request for money and cavalry. Well, almost. They grant the horsemen but not the horses.

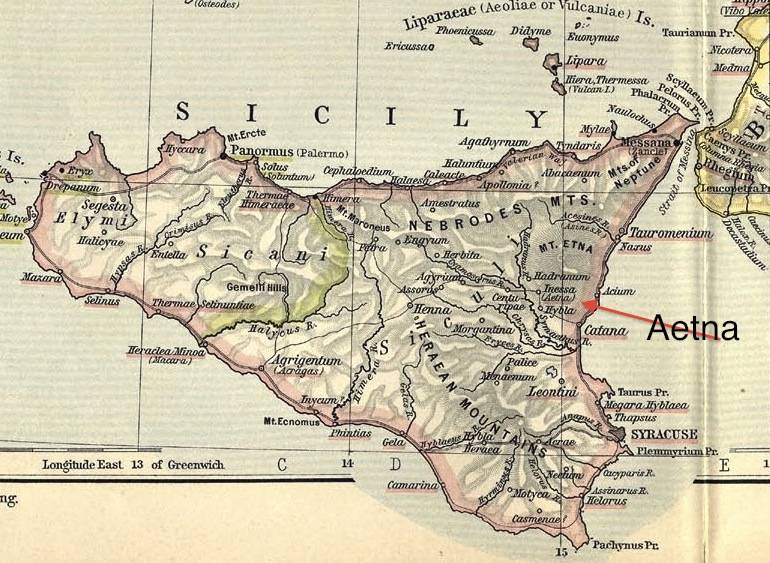

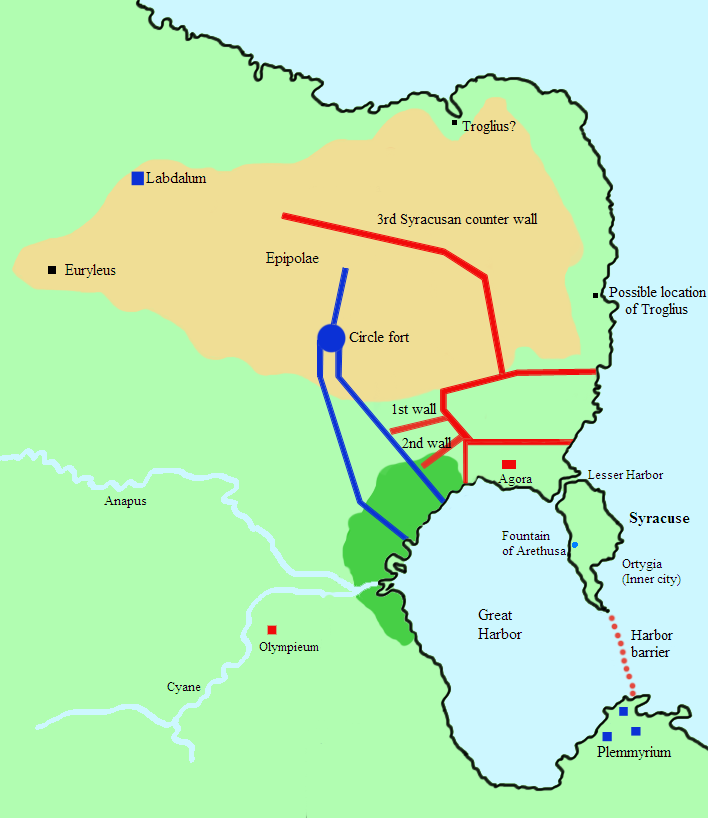

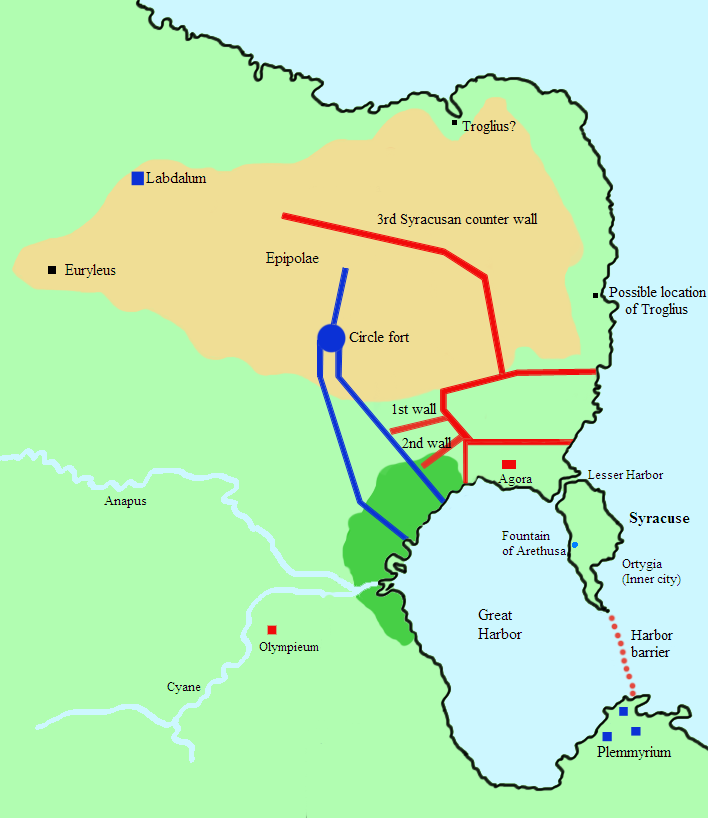

As the season turns favorable for expeditions, the Athenians burn crops and harass towns in Sicily…not exactly helpful for public relations. Syracuse determines that Epipolae, the rocky ground just north of the city, was crucial for their defense and send troops to guard this area. At about the same time the Athenians land their forces to the north of this point and occupy Epipolae just as Syracusian troops arrive. Even though the troops from Syracuse were surprised, they stood their ground, fought, and were defeated. Instead of holding this position, though, the Athenian troops move to a higher plateau at Labdalum and build a fort. At this time Egesta comes through on their promise to deliver a cavalry (plus horses for the Athenians), helping the generals felt secure in their position to begin building fortifications. The Syracusians attempt to disrupt the construction but their forces are in disarray and easily picked off when engaged.

Instead of direct attack, the Syracusians attempt to build counterwalls to intercept and stop the Athenian walls. (I can see Tristram’s Uncle Toby becoming interested in the story again at this point) The Athenians note that the Syracusian guards for this construction kept negligent watch and so they were able, by catching them at noon when the fewest guards were present, to storm and tear the counterwalls down.

The Syracusians attempt to build a second counterwall but again the Athenians capture and raze it. During this battle Lamachus is killed, leaving Nicias as the lone Athenian general. Lamachus and Alcibiades had shown the most aggressive tendencies in their plans, but Thucydides (and many other Athenians) questioned Alcibiades’ motives. To make matters worse, at this point Nicias was infirm and had been left at the plateau’s fortification upon Epipolae. The Syracusians, seeing a turn of the tide in battle, swarm toward the circle fort on Epipolae to destroy the fortifications, assuming it had been left unguarded. Nicias has the servants set fires and burn whatever is available to protect themselves and the fortifications. The Syracusians retire from the fire and Athenian reinforcements return to save Nicias.

It’s at this point that the Athenians make another strategic blunder. They begin building a double wall from the circle fort on Epipolae south and toward the harbor instead of finishing a single wall completely around Syracuse—the north projection from Epipolae was not finished yet. On the plus side, many cities that had remained on the sidelines began to side with Athens as they observed “the way of fortune”. The Syracusians receiving no help from Peloponnesus split into warring factions, some wanting to capitulate. The generals in Syracuse were sacked and new ones appointed. News of these setbacks reached Gylippus as he was on his way to Sicily. He speeds to Italy and unsuccessfully tries to enlist help but is turned down. In yet another blunder, Nicias hears of Gylippus’ approach but takes no precautions to intercept him, thinking the few ships he has to be of no significance.

Although things are going Athens’ way in many aspects, I’ve noted several decisions Nicias has made that will come back to haunt him. It’s at this point the leaders in Athens make one of the biggest mistakes of the war. In response to the Spartans invading and wasting land in Argos, the Athenians and Argive forces begin to conduct raids along the Peloponnesus, plundering coastal cities. All of the minor skirmishes in Greece that had taken place during the peace did not seem to constitute a breach of the peace between Athens and Sparta. According to Thucydides, though, the direct Athenian action against Peloponnesian cities gave Sparta the “most justifiable cause to fight against the Athenians.” Book Six ends on this ominous note—Athens has completely bungled the peace.