The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas discussion: Chapters 25 – 61

Brás Cubas

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Virgília

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Brás Cubas

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ! . .

. . ! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . !Virgília

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ?Brás Cubas

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . !Virgília

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . !— From Chapter 40, titled “The Old Dialogue of Adam and Eve”

These chapters follow Brás Cubas through the grief after his mother’s death, his reclusion away from Rio de Janeiro, his father’s two offers (marriage and a job), his dalliance with Eusébia, the return to Rio where he meets Marcela again, the marriage and job arrangement are lost, his father’s death and Brás seclusion, his affair with Virgília, and his meeting with Quincas Borba (an old classmate). I’ve probably stressed or included some scenes not necessary for a summary, but I mention them to show how much the text flies along in fifty pages.

A few themes and subjects have emerged in the book to date, which is why I’m keeping to the shorter post schedule—this post represents the halfway mark of the book, yet so far there have been many deep reflections on death, reading, writing, love, slavery, class, and time as well as many other things (including worms). Death continues to be at the forefront of the novel, and not just because the novel is narrated by a dead man. Brás Cubas’ mother died just before this section of the book and the first part of these chapters sees the son secluding himself at a family house away from the city (but not from living). In looking back on this period, Brás Cubas lets us know that “Death didn’t make me sour, or unjust.” That’s about as much information we have received so far from the ‘author’ on his experience in the afterlife. During his seclusion, his father tries to instill a sense of what is important in life (or at least to the father): “Fear obscurity, Brás, flee from the negligible.” Brás’ self-absorption, a hostage to others’ opinions, ceases to be a contradiction in his definition of what it means to live. Brás tries to shrug off any responsibility for his father’s death, even though he realizes his failure to secure the marriage or the job probably had a role. Once again, Fate and Providence are the usual scapegoats for Brás: “He was to die and he died.”

Reading plays an important role in his life after his mother’s death. During his seclusion he immerses himself in reading for consolation, finding Shakespeare’s words comforting. The literary references throughout the book demonstrate how Brás’ world is viewed through the lens of reading. Of all the things he could point out about the rival for Virgília’s affections, he chooses to highlight Lobo Neves’ admission that he doesn’t understand literature. In addition to reading, Brás begins to compare life to a play. Plays by Shakespeare, Moliere, and other authors are mentioned directly or by allusion. “My brain was a stage on which plays of all kinds were presented” helps bring into focus what is going on inside Brás’ thoughts (as well as explaining his actions). He compares life to a tragedy, with everyone else as a “walk-on” in his life. Brás isn’t the only one that feels this way. In describing his life in politics, Lobo Neves’ description portrays it as a role in a play that leads to “nothing…nothing…nothing.”

The writing style hasn’t changed from the first post’s section, but his digressions are now being blamed on his “playful pen.” He mentioned in the Preface that he had a playful pen that was dipped in melancholy ink, the combination of which would determine the mood of the story. While alive and reclusive, he not only reads but writes (politics and literature), his half-dead state assisting him in his compositions. Brás continues to address the reader directly, adding Stere-like touches in chapters such as the excerpt at the top of this post.

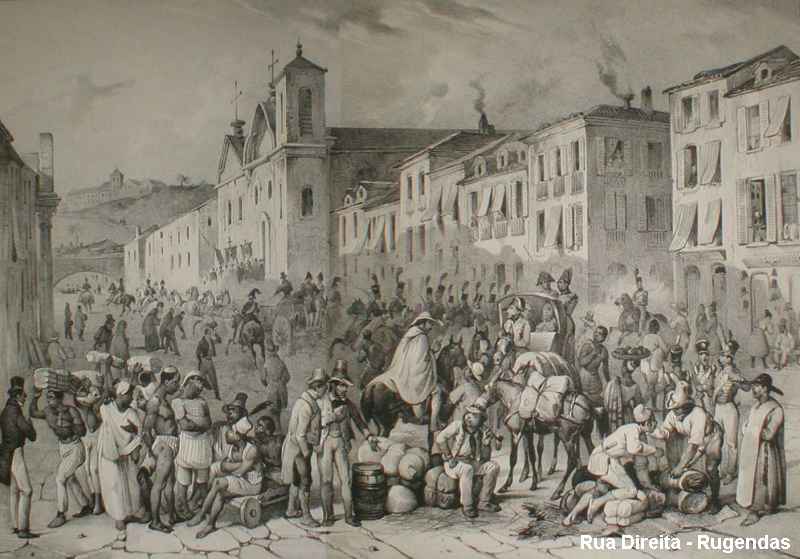

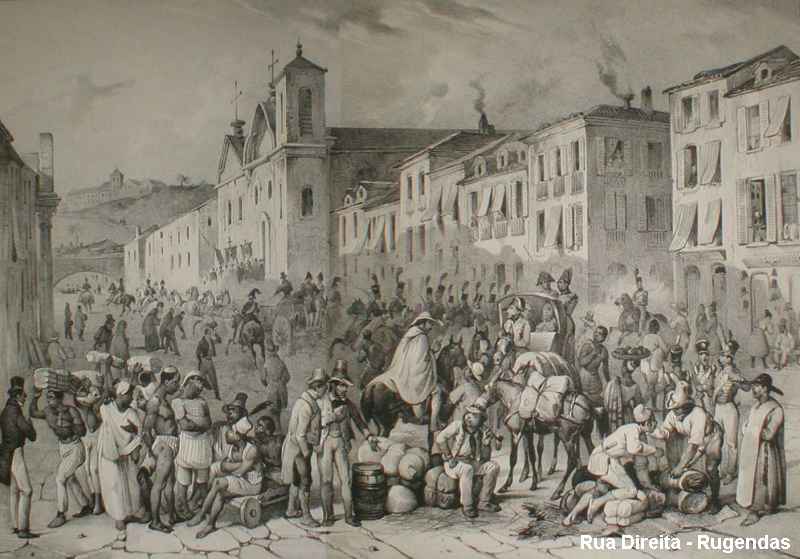

I found it interesting that Brás describes his falling in love as a delirium after he detailed the delirium just before his death. While I don’t think he means to associate love and death directly, both produce similar feelings in the author while at the same time yielding different states. However, you wonder how much depth Brás is capable of after seeing him shrug off all feelings toward Eusébia because of her physical defect. The words used for his and Virgília’s love indicate a slavishness that neither can control, in sharp contrast to the freedom he associates with death. The shackles he metaphorically feels is in sharp contrast to the actual slavery described in the novel. While slavery stands somewhat in the background, it comes to the forefront after the death of Brás’ father. Brás and his sister fight over the family inventory list, of which the servants are included…a sharp reminder of how slaves were viewed. The difference between castes floats beneath the surface most of the time, but occasionally makes itself felt in comparing the idle rich with much lower classes. While it must be nice to be able to bask in top tier’s “sensuality of boredom”, it doesn’t seem to benefit them much.

The fleeting nature of things is highlighted over and over again as times demonstrates its power. Brás’ grandfather clock audibly marks the passing of time that is going on around him and the countless changes he sees: deaths in the family, fading of beauty, loss of friendships, and change in social status. The past “lacerates and kisses” Brás with the pockmarked face of Marcela, while seeing his old classmate Quincas Borba (and being cheated by him) achieves the same effect. In each case it is the “remembrances of childhood, and once again the comparison, the conclusion” that lacerates him the most. These “burdens of the past” usually bring out something negative in Brás, oftentimes the “yellow flower” of hypochondria, and he seeks to console himself in the present. The irony in Brás’ playful pen can’t possibly be thicker at this point: while he once viewed the present as a refuge, his present is spent recalling the burdens and joys of the past. The current “abyss of the Inexplicable” and his memories are all he has now.

There are many playful conceits that I’m not going to touch on that enrich this section: the reason for the tip of your nose (an appropriate Panglossian deduction), the equivalency of windows, Brás’ inner lady and inner urchin, and Quincas Borba’s philosophy of misery, for example. All need to be experienced in context for full impact, much like the opening “dialogue” of this post. Ah well, I’ll do what I can with the next quarter of the book in the next post…