Rambling on: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab by Bohumil Hrabal

English translation by David Short

Afterword by Václav Kadlec

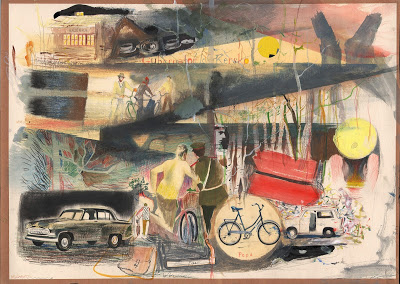

Illustrations by Jiří Grus

Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press

ISBN: 978-80-246-2316-0

Dear colleagues and friends,

On the occasion of 100th anniversary of Bohumil Hrabal’s birth, we would like to present two new additions to the Fiction Series.

The collection of stories entitled Rukověť pábitelského učně (Rambling on: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab) contains Bohumil Hrabal’s 1970s short stories. They are mostly texts written in and inspired by the community in Kersko. Our collection strives to recreate the author’s original intentions, and thus presents even the stories left out due to the 1970s censorship.Both Czech and English language versions are accompanied by Jiří Grus’s original illustrations.

(from the Karolinum Press website)

One afternoon I was in a little restaurant/bar listening to a truck driver tell the most wonderful stories. No matter how outlandish or grotesque the tales, he could sell them as having really happened. Like the time he crested a hill in backwoods Arkansas and plowed into a herd of sheep…when you laugh at a man describing how he used a tire tool to pry dead sheep from his wheel wells you know you’re listening to a master storyteller.

I thought of that truck driver—what it takes and what it means to be a master storyteller—as I read these wonderful stories by Bohumil Hrabal.

My posts on Hrabal have made it clear how much I enjoy his books, and this collection of short stories may be my favorite yet. The reader is immersed in the sylvan Kersko settlement located in Bohemia, where the forest, cottages, byres, and pubs are populated with memorable people and animals.

And the characters…ah, these creations are wonderful. There’s an old man with wild hair who enjoys watching his goats fight over the window seat of the car when he drives them to pasture. There’s two friends, both paralyzed below the waist, who share an insatiable love for life and beer—one of them permanently keeps a bottle-opener hanging from a string on his wheelchair. There’s a friend with the best intentions in the world repeatedly messing everything up, not to mention frequently missing a turn in the road and wrecking his car. There’s a nun who lovingly deals with her damaged wards. These characters are poignant and surprisingly real, expanding to a third dimension outside of the page.

The stories are funny and often frivolous, but they also take on a serious and bittersweet tone when broken dreams of what might have been come into play. Dark and troubling components, barely lurking beneath the surface, add ambiguity on how to read Hrabal’s stories. I’ll focus on some recurring themes in these stories that highlight that ambiguity.

Hrabal had a reputation for sitting in the pub, closely watching what went on around him and engaging in spirited conversations. The funniest stories in this collection usually involve a pub (or drinking in general) and the narrator’s neighbors and friends. The two paralyzed friends, for example, demonstrate a beautiful testament to true friendship. Friendships take on added dimensions as other components are added, though. Pranks played by friends on each other make the reader question if there is any difference in how they would treat people they despise. The mood swings of a pub owner make one narrator question if the two were really friends, acknowledging he goes through the same swings, treating his own friends the same way at times (although he forgives him during his next “up” swing). The loss of a friend in a story leads to a question of who was going to amuse the pub goers now, as if the value of a friend is solely based on entertainment value.

Entertainment value leads to a side-topic—the role of alcohol in these stories. The narrator of “Lucy and Polly” tells us that

from six o’clock onwards the sole preoccupation of any true man of Kresko and its forests is to spend a pleasant evening over a pint in the pub, and all the banter and chit-chat, the arguments and imbecilities are a brilliant way to unwind from our daily tribulations…”. (229)

Alcohol provides not just a social lubricant or relaxation but a form of entertainment in itself. Pub patrons laugh at each other’s misfortunes on their way home from a night of drinking. In my favorite story, “Beatrice,” the narrator describes children with mental and physical defects as having a “mantle of mercy” around them, shielding them from the horrors of their life. Alcohol provides a similar “mantle of mercy” for many of the characters in these stories as dreams are broken and power is wielded arbitrarily against them. In the extended opening sentence of “An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of Gab,” which takes up almost the whole story, the narrator extols the usefulness of doing silly things like getting drunk “while there’s still plenty of time,” but also hints at the worthlessness of his life that such behavior masks. It’s one of many double-edged swords Hrabal wields in his stories.

The greatest ambiguity, though, comes in the role of storytelling. The collection of stories in this book is a testament and celebration of the art of storytelling. Questions about storytelling’s role in society and its purpose for listeners keep bubbling up in the text. The best storytellers in these stories usually have some sort of damage. In “Fining Salami” the storyteller talks about how great life was until his wife left. The narrator remarks that his stories have been repeated many times, not just to provide comfort but more than likely an escape. Details in stories that should cause shame reveal a type of pride, allowing the teller to share his embarrassment while embellishing what happened. Since many of the stories deal with a distant past, they seem to afford the teller a way to revel in youth again. While the stories offer a wistful look back, they often provide a painful comparison with the present.

The story of the troubled children mentioned in “Beatrice” provides a good example of the ambiguity in Hrabal’s use of storytelling. The narrator lovingly describes the children and their behavior, but he seems to revel in their pitiful situation since it provides a great story. When the narrator asks Sister Beatrice if it would have been better if the children had never been born, she replies “Homer was born blind,” a non sequitur given the dire condition of these kids. Instead of applying her reply to the children, though, the narrator reflects on how Homer continues to live through his stories. Many of these tales highlight characters who similarly seem to want to live on forever through their tales. Since Hrabal saw the state destroy entire printing runs of his books, it’s difficult not to apply this situation to him, too. As the narrator in “Beatrice” reflects, there is a “sacred radiance that irradiates everything” making what happens beautiful and breathtaking, but it is memory and storytelling that makes it last beyond the fleeting moment.

This collection of stories was originally subject to the Czechoslovakian censors. As in his other books, Hrabal’s subversion wavers between subtle jabs and over-the-top farce. The local police commandant, his chest full of medals, makes several appearances in these stories (once as a narrator). The villagers acquiesce to the arbitrary whims of officials and silly laws. I get the feeling that Hrabal isn’t necessarily political, it’s just that his experience with Communists provides so much rich material. There’s not many places you can read a great line like “We guard the substance of socialism against the foe, even if that foe turns out to be a feral cow.” Hrabal turns out to be an equal-opportunity lampooner, though. As Václav Kadlec points out in the Afterword, Hrabal focuses on the materialism of Czechs in his stories. While there is a subtle “West is best” message, providing soft jibes at the centrally guided state, Hrabal also highlights the dark side in consumerism. One narrator’s friend, obsessed with finding bargains, is “in reality a poor wretch who wished not to have to contemplate the pointlessness of not only his life but all life.” That escapism, whether through shopping, storytelling, or alcohol, provides a central theme to these stories.

There’s more in these stories, including echoes of history and meditations on eventual death, for the reader to explore. Thanks to Karolinum Press for putting out another wonderful book (and the University of Chicago Press for distributing it in the U.S.). I think this collection would be an excellent starting point for a reader wanting an introduction to Hrabal’s writing. Very highly recommended.

Note: I’m working on getting a copy of Jiří Menzel’s movie version of “The Snowdrop Festival” that has English subtitles. I’ll post on it if I’m successful.

Update: my notes on the movie can be found here.

Update: an excerpt from what Hrabal originally had as the introduction to the collection of stories, where he credits Jaroslav Hašek as the inventor of the cock-and-bull story. Or is it the beer-hall story?

Note: A version of this review is also posted at The Mookse and the Gripes.

Update: There have been plenty of pieces written in celebration of what would have been Hrabal’s 100th birthday this year. I’ll include a few links from Radio Prague I have enjoyed:

Fred

The characters sound fascinating. I checked the library and they don't have this book.

However, they do have an ebook edition of _Too Loud a Solitude_ but since I don't have a reader, that's out.

The library also has a film, _Closely Watched Trains_, which apparently is based on a novel by Hrabal.

Do you know anything about _Too Loud a Solitude_ or _Closely Watched Trains_?

Dwight

I've not read Closely Watched Trains, something I mean to fix this year. The movie based on the book was great, so I'm looking forward to reading it. (I think the movie's English subtitles are being updated by Alex Zucker but I don't have any date on when to see a new release.)

I really enjoyed Too Loud a Solitude, and you can read some of my notes on it. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

The following quote from Václav Kadlec's Afterword of this book (which just came out…hopefully your library will get it soon) will help with Too Loud a Solitude:

"In 1970 Mladá fronta published two of Hrabal’s books—Poupata (Buds, 35,000 copies) and Domácí (Homework, 26,000 copies). Both did come out in the stated print-runs, but both were then banned. The spanking new books were trucked to a state recycling centre and destroyed (except for the small numbers salvaged by Hrabal’s wife Eliška, who was, by a whim of fate, employed at that very centre). Thus did Bohumil Hrabal become (in his own words) a writer to be disposed of."

Hopefully there's a way for you to access the e-book, but I'm guessing Closely Watched Trains would be a good introduction to Hrabal, too.

Dwight

And yes, the characters in this are fascinating, especially the drinking buddies. The stories start off in Cheers lovability (or Foster Brooks or Arthur Bach territory) but usually end up closer to the Replacements' "Here Comes a Regular" reality.

Fred

Dwight,

OK, thanks for the information. A new name for my TBR and TBV list.

Janakuba

This title will soon be available as an e-book in Amazon e-shop.