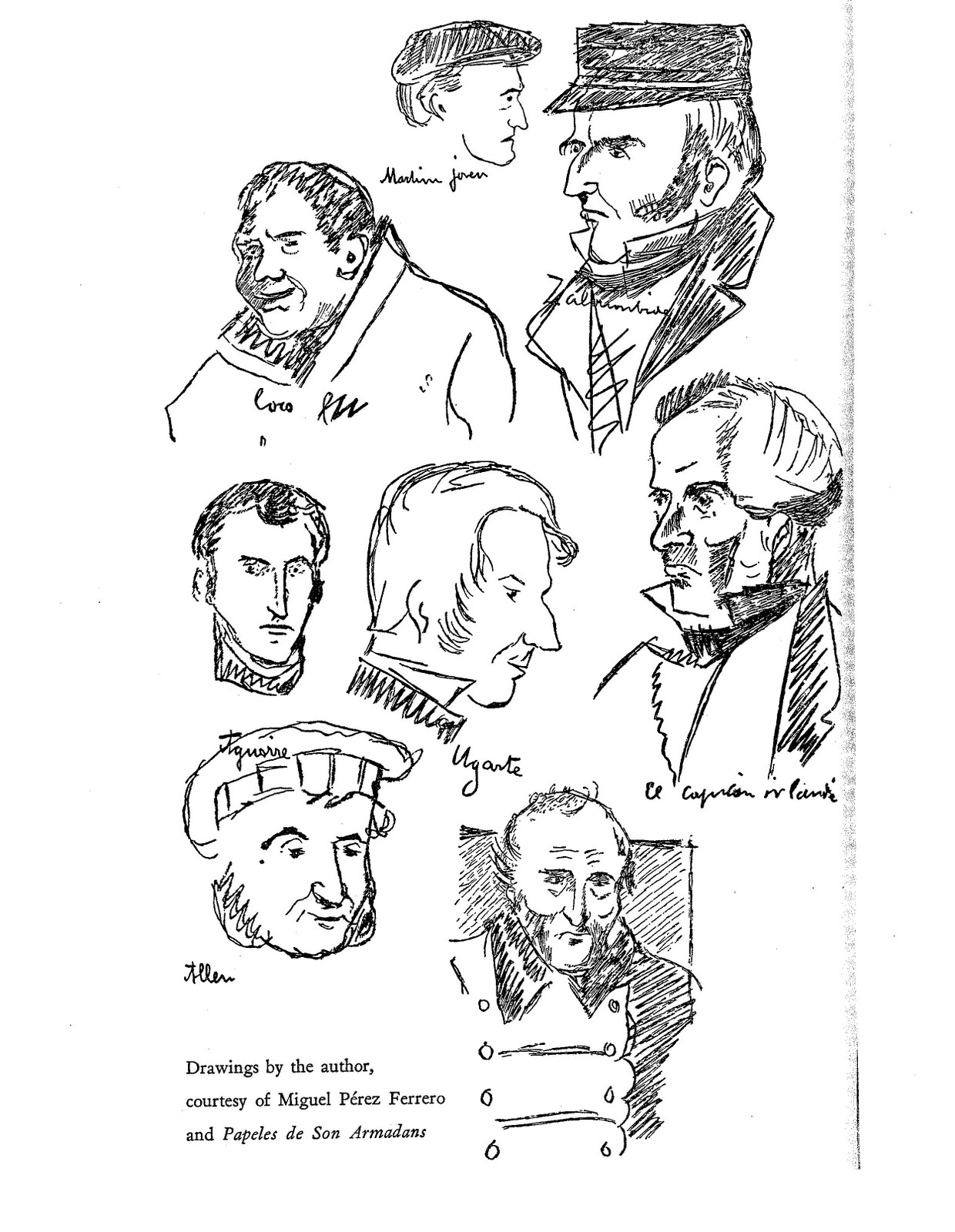

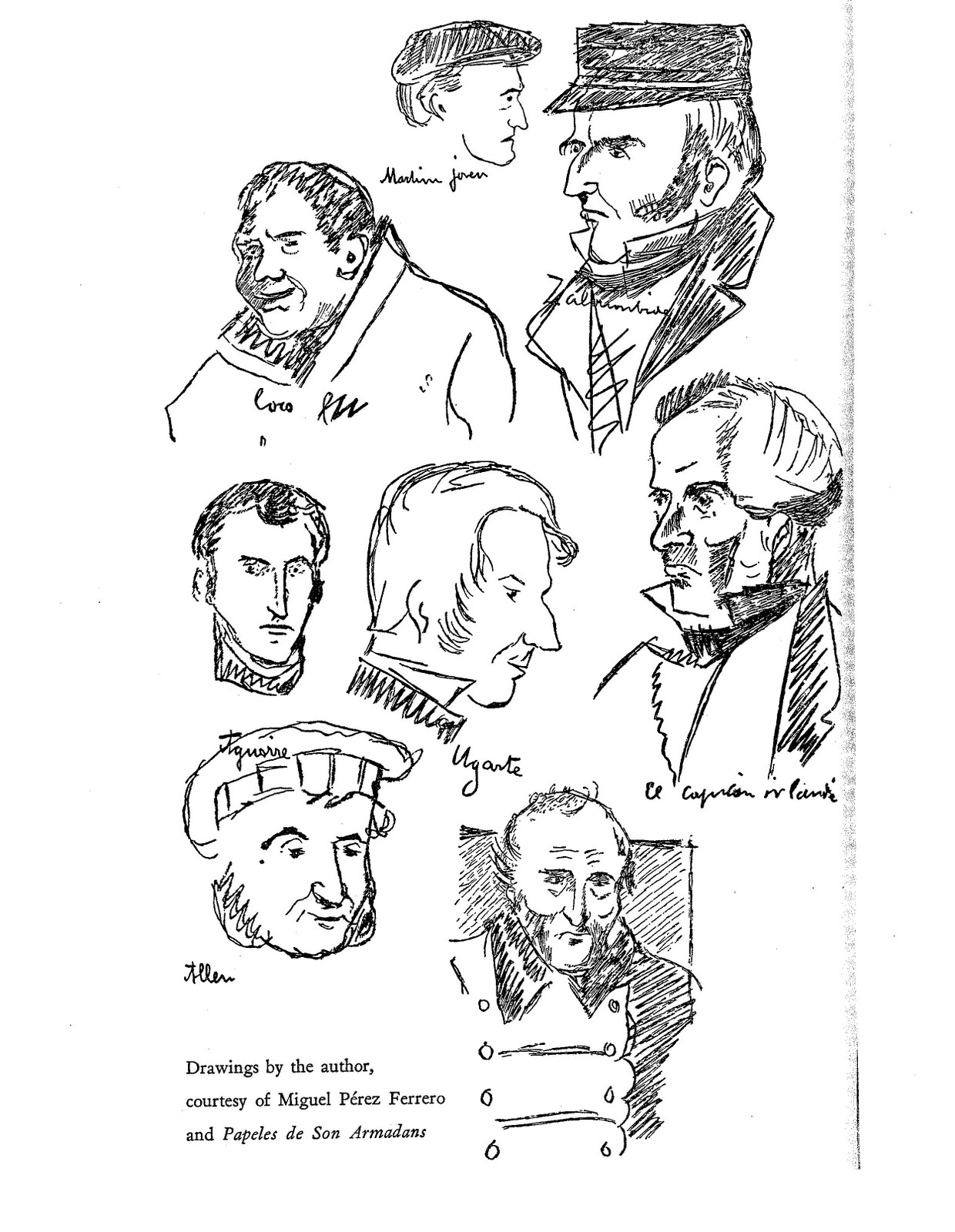

The Restlessness of Shanti Andía discussion

(Characters from The Restlessness of Shanti Andía)

At sea I lost the notion of time. Aboard ship the days are long, and yet the years, sum of the days, are short, and they fly by and are gone. Time has sped for me. The thought of the past, once youth has been left behind, is like a wound in the soul, a wound which flows continually and floods one with sadness. The enter route traversed seems like an Appian Way sown with tombs. … I do not know why it is that the past is flooded with a magical melancholy—it is hard to understand why it should be. One recalls clearly that one was not happy in those days, that one was possessed by restlessness and sorrows, and nevertheless, one has the impression that the sun then shone brighter and that the blue of the sky was purer and more splendid.

– from Book 3, Chapter 1 of The Restlessness of Shanti Andía

From John Dos Passos (Chapter V, Part IV): “Nothing that Baroja has written since [The Tree of Knowledge] is quite on the same level. … Las Inquietudes de Shanti Andía (The Anxieties of Shanti Andía), a story of Basque seamen which contains a charming picture of a childhood in a seaside village in Guipuzcoa, delightful as it is to read, is too muddled in romantic claptrap to add much to his fame.”

The first three books are enchanted. Baroja’s “wounds” are on display, the magical melancholy making it easy for a reader to recall his own wounds. Fortunately the author is correct, not just for himself but for me as well—distance makes everything seem brighter and sunnier than it felt at the time. Baroja paints a picture of the Basque coast that sticks with me, from the sound of the women (whose screeches mimic the seagulls) to the lure and danger of the ocean. Little happens in this section, or rather little action is detailed. The languid descriptions of his hometown and the characters found there, each unique but all sharing an “off” quality, provide the “charming picture” that John Dos Passos noted. There are few characters well off in this seaside town. Most work hard to survive while others laze about, choosing to barely exist but on their own terms. While this section follows Santiago de Andía (Shanti) until he is twenty-eight years old, it isn’t a coming-of-age story as much as an exploration into the places and events that shaped who he is.

The remaining books, four through seven, follow the exploits of Shanti’s uncle, Juan de Aguirre. The quote from TIME in the resources post covers the elements: “There is a duel, a mutiny, piracy, the slave trade, an escape from prison, changed identities, a kidnapping, even buried treasure.” I didn’t see it as “romantic claptrap” as John Dos Passos described it. This section felt like a Walter Scott story, several of which are specifically mentioned in these chapters. The mystery of his uncle unfolds, second-hand initially and then in the form of a memoir, providing a “happily ever after” ending. While the storyline is fun to follow, the details of life at sea—life on a slave ship in particular—were fascinating.

A quick note: I’m struck by the number of family ties involving lovers in Spanish literature from the late-19th/early-20th century that I’ve happened to read recently. Shanti falls in love with his first cousin Mary. Galdos’ Fortunata and Jacinta have cousins marrying as well. And then there is the “are they or are they not siblings” question running through Eça de Queirós’ The Maias. I’m assuming it’s just the luck of the draw in what I’ve chosen to read since it isn’t an uncommon theme, but still it seems a little strange that such a high percentage of what I’ve picked has this device in it.

I thoroughly enjoyed the first half of the book and it has me wanting to read more of Baroja’s work. Unfortunately English translations of his highly regarded works are hard to come by. It looks like I’ll be exploring some of a nearby university’s library policy for non-students.

Some online resources for the book, as well as Baroja, can be found here.