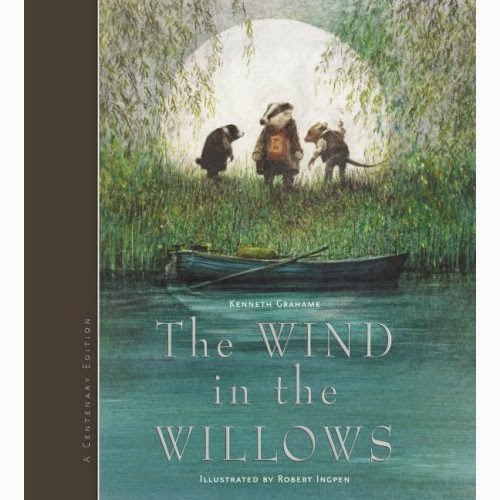

The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

How could I have **not** read this book before now? The boys and I are thoroughly enjoying it. We just read “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” chapter and it has to be one of the most beautiful chapters I’ve ever read.

The willow-wren was twittering his thin little song, hidden himself in the dark selvedge of the river bank. Though it was past ten o’clock at night, the sky still clung to and retained some lingering skirts of light from the departed day; and the sullen heats of the torrid afternoon broke up and rolled away at the dispersing touch of the cool fingers of the short midsummer night. Mole lay stretched on the bank, still panting from the stress of the fierce day that had been cloudless from dawn to late sunset, and waited for his friend to return. He had been on the river with some companions, leaving the Water Rat free to keep an engagement of long standing with Otter; and he had come back to find the house dark and deserted, and no sign of Rat, who was doubtless keeping it up late with his old comrade. It was still too hot to think of staying indoors, so he lay on some cool dock-leaves, and thought over the past day and its doings, and how very good they all had been.

The descriptions get even better, especially of the river in the evening. For anyone not familiar with the book (I can’t be the only one, can I? Oh, and if you aren’t familiar with it, go get a copy. Now), the chapter covers good friends Rat and Mole searching for Otter’s missing son. They find Pan protecting the otter, playing his pipes to attract the pair. His second gift to them, though, proves to be even more humane.

Then the two animals, crouching to the earth, bowed their heads and did worship.

Sudden and magnificent, the sun’s broad golden disc showed itself over the horizon facing them; and the first rays, shooting across the level water-meadows, took the animals full in the eyes and dazzled them. When they were able to look once more, the Vision had vanished, and the air was full of the carol of birds that hailed the dawn.

As the stared blankly in dumb misery deepening as the slowly realized all they had seen and all they had lost, a capricious little breeze, dancing up from the surface of the water, tossed the aspens, shook the dewy roses and blew lightly and caressingly in their faces; and with its soft touch came instant oblivion. For this is the last best gift that the kindly demigod is careful to bestow on those to whom he has revealed himself in their helping: the gift of forgetfulness. Lest the awful remembrance should remain and grow, and overshadow mirth and pleasure, and the great haunting memory should spoil all the after-lives of little animals helped out of difficulties, in order that they should be happy and lighthearted as before.

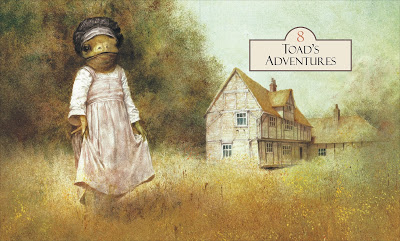

The Sterling Children’s Books edition, illustrated by Robert Ingpen, is a delight to look at. We spend a lot of time just looking through the illustrations, lining everything up with the text. And then there’s illustrations like the one below (click for much more detail). Surely I can’t be the only one that thought of Andrew Wyeth’s painting “Christina’s World.” Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride may be long gone (I need to see if I still have my “Save Toad” t-shirt), but Kenneth Grahame’s tale lives on.

Amateur Reader (Tom)

I have seen people – more than one, though heck if I can remember who – object to exactly that chapter. They see Pan as some kind of intrusion from another world or reality or something.

I think these folks are nuts; I'm with you.

Dwight

If moles and rats can talk and if frogs can drive cars, it's not much of a stretch to have Pan appear in the story. It is a lull…definitely a diversion. But goodness, it's a beautiful one.

scott g.f.bailey

One of my favorite books of all time. You're right, the Pan chapter is just lovely. Who do people think the rats and moles would worship, anyway? It's all of a piece with the rest of the book.

Though I admit to liking best the chapter where Rat goes forth with his brace of pistols and his ugly cudgel, in order to rescue Mole from the forest beasts.

And who doesn't love Toad?

Dwight

We just read the chapter where Toad escapes prison as a washerwoman. I was almost giggling at times. Everything has been pitch-perfect so far.

The boys will have a workshop on the book next Wednesday. I'm almost wishing I could participate!

I meant to mention there are several versions of WitW on YouTube. We watched the series of videos titled "The Adventures of Mole" and it was faithful to the book (with a couple of songs thrown in). It covers the first third of the book.

George

A dissenting voice: I can't stand the Pan chapter. I don't get that period paganism–Saki's story "The Music on the Hill" is another one I don't like, and I find E.M. Forster's "The Celestial Railway" bogus.

I recommend to those who care for it a glance at S.J. Perelman's "Cloudland Revisited: Antic Hey-Hey", and (mentioned in that) Max Beerbhom's "Hilary Maltby and Stephen Braxton".

I do like the rest of the book, though, and (since you mention the chapter) fondly remember Toad working out the gypsy's offer of "a shilling a leg".

Dwight

George, no problem. The chapter is a slight step outside the rest of the book, but again given the basic premises of the story I don't find it jarring. Maybe I'm slightly immune to it by the kids' interest in Rick Riordan's books.

The descriptions, regardless, I found sublime.

Amateur Reader (Tom)

I am so glad George stopped by – I can now be sure I was not inventing the objection to the Pan chapter.

George is so right that it is always worth a return to Max Beerbohm. I just revisited "Hilary Maltby and Stephen Braxton" at his suggestion:

"From the time of Nathaniel Hawthorne to the outbreak of the War, current literature did not suffer from any lack of fauns. But when Braxton's first book appeared fauns had still an air of novelty about them. We had not tired of them and their hoofs and their slanting eyes and their quiet ways of coming suddenly out of woods to wean quiet English villages from respectability. We did tire later."

Found in Seven Men and Two Others.