What the Emperor Cannot Do by Vlas Doroshevich

Translated by Rowen Glie (in collaboration with Ronald M. Landau) and John Dewey

Glas New Russian Writing: 2012 (Volume 53)

ISBN 978-5-7172-0094-3

Earlier this year I expressed my admiration for the works of Anatoly Mariengof published by Glas (Cynics and A Novel Without Lies). Glas editor Natasha Perova provided me with additional volumes by the press and I’m belatedly providing a review of this wonderful collection of fables by Vlas Doroshevich (1864 – 1922), one of Russia’s most popular writers of his day. (This is part of my “get semi-caught up on things before the end of the year” project.) Doroshevich worked as a journalist with Anton Chekhov, who became a friend and model for this author. His expose on Tsarist labor camps, Sakhalin (the English translation is titled Russia’s Penal Colony in the Far East and the World War I book The Way of the Cross (1915) are his most famous works. After traveling to the island of Sakhalin in 1897 for his report, Doroshevich traveled in the East, providing inspiration for many of these tales.

Three of the stories, “Rewards,” “Rain,” and “The Emperor’s First Outing,” can be found at the Glas site [sorry, link no longer working]. These stories provide a very good overview of the Chinese tales.

Michael Stein had the first review of the collection I read. The review can be found here, which includes a little on Doroshevich’s life and some detail and comments on the stories: “As whimsical as these stories are they have a cumulative effect that borders on despair. Doroshevich deftly manages to vary them in terms of the plot twist while continuing to hammer the point home that justice is unobtainable on heaven or earth.” In his review, Stein goes into detail about the story “The Green Bird,” which was later included in the online literary magazine B O D Y.

The introductory essay “The Russian King of the Feuilleton,” written by the editors, includes a nice summary of what the tales are about as well as providing Doroshevich’s outlook:

Doroshevich was not a Socialist and never belonged to any political party. But as a man with a warm heart and a sharp mind, he hated injustice and cruelty, the servility of the weak and poor, and the insolence of the strong and rich. Doroshevich could not stand tyranny in any form while meek acceptance of tyranny made him livid. …

Doroshevich’s tales are a mixture of pure fantasy, irony, and often despair caused by the fact that between men in power living in their ivory towers and the people they rule over there is a corrupt bureaucracy–an “establishment”. Any effort by a man in power–an “Emperor of China” or a “Caliph”–is always thwarted by his own “establishment” created to execute his orders. The “Emperor” or “Caliph” themselves are kept so far from reality by their underlings that the most obvious solution to any problem often escapes them. Any chance for a better solution devised by the ruler himself or his corrupt “establishment” results in greater suffering for the very people the decree was supposed to help. Whatever their subject, these tales are unexpected, exciting, colorful, and supremely readable. (10-11)

They are indeed. Tales include instances of an Emperor trying to bring joy to people, only to see his wishes (by design or misconstruction) turn into a cause for his subject(s)’s unhappiness. Often the Emperor or Caliph are undone by traditions, protocols, and/or holy laws put in place to insure power remains with the ruler, bureaucrats, and/or religious leaders. The conflict between these ruling classes provides a constant source of friction. When any of these powers are challenged, the entrenched leaders react with many available tools, from direct stifling of dissent to subtle misdirection. The stories available in the above links provide a good overview of the types of stories in the collection.

Like any good fable, many in this collection stand the test of time and are still relevant today. My favorite story is “Not the Right Heels” since it applies just as much to current affairs as it did in Doroshevich’s time. The title refers to a common punishment of striking a subject’s heels with a bamboo cane. The problem of proper punishment, though, is to strike the right heels, otherwise what was meant as an incentive (or maybe better put, as a disincentive) perverts the system. In this case, the Emperor’s initial giddiness that eggs in the kingdom cost a golden coin becomes a concern when a sage points out that people will starve from the high cost. Seven bamboo groves are harvested to beat the heels of the peasants selling eggs for that exorbitant price. The price of eggs, of course, go up as the peasants want two gold coins per egg: “One golden coin for each egg and one for the bamboo strokes.” The Emperor’s council decides the bamboo was applied to the wrong heels, so they recommend punishing the buyers of eggs for paying such a high price. It takes three days to punish the “money squanderers.” On the fourth day, the price of eggs doubles to four golden coins, available only on the black market. The sage that had initially raised concern at the high cost of eggs is now at death’s door from starvation. The Emperor, instead of simply providing food to the sage, continues to try to drive down the cost of eggs. This time the “right heels” have been found–the hens are the guilty party since they are laying expensive eggs. After a full day of their heels being beaten, the hens stop laying eggs. The sage dies, not before imparting his final judgment on how history will remember this Emperor: ” ‘He meant well. He had only one misfortune; he never could find the right heels.’ But do not worry, Son of Heaven. This is the fate of many, many Emperors on this earth. They always punish the wrong heels.” (39)

It’s not a far stretch to apply this fable to current headlines…as are many other lessons to be taken away from these tales. Many tales revolve a common theme of good intentions: “This illustrates the weak point of all sultans: they think that they can make people not only rich, strong, and noble, but also happy.” (113) While a couple of the tales are heavy-handed in their approach and message, most of the fables excel because Doroshevich takes a light, humorous touch. The humor borders on the absurd at times, treating the suffering and seriousness of the topics with irony and comedy. I agree with Michael Stein that the Chinese tales are the strongest, but there are plenty of good tales in the Arabian and Indian section.

Read the free stories in the above links and see how you like them. The first three are from the Chinese section while “The Green Bird” is from the Arabian tales. Highly recommended.

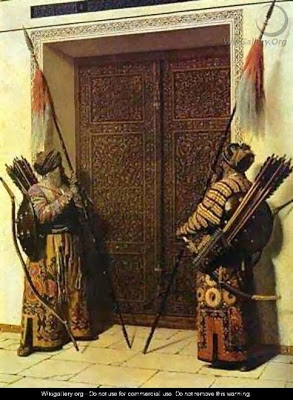

Picture source

This page (website no longer exists) gives the story behind the painting and probably the reason Vereshchagin’s work was chosen for the cover:

“Vasily Vereshchagin won fame through works which asserted in Russian art the theme of the Orient.”