Parade’s End summary

This, Tietjens thought, is England! A man and a maid walk through Kentish grass-fields: the grass ripe for the scythe. The man honourable, clean, upright; the maid virtuous, clean, vigorous: he of good birth; she of birth quite as good; each filled with a too good breakfast that each could yet capably digest. Each come just from an admirably appointed establishment: a table surrounded by the best people: their promenade sanctioned, as it were by the Church–two clergy–the State: two Government officials; by mothers, friends, old maids…Each knew the names of birds that piped and grasses that bowed: chaffinch, greenfinch, yellow-ammer (not, my dear, hammer! amonrer from the Middle High German for “finch”), garden warbler, Dartford warbler, pied-wagtail, known as “dishwasher.” (These charming local dialect names.) Marguerites over the grass, stretching in an infinite white blaze: grasses purple in a haze to the far distant hedgerow: coltsfoot, wild white clover, sainfoin, Italian rye grass (all technical names that the best people must know: the best grass mixture for permanent pasture on the Wealden loam). In the hedge: our lady’s bedstraw: dead-nettle: bachelor’s button (but in Sussex they call it ragged robin, my dear): so interesting! Cowslip (paigle, you know from the old French pasque, meaning Easter); burr, burdock (farmer that thy wife may thrive, but not burr and burdock wive!); violet leaves, the flowers of course over; black bryony; wild clematis, later it’s old man’s beard; purple loose-strife. (That our young maid’s long purples call and literal shepherds give a grosser name. So racy of the soil!)…Walk, then, through the field, gallant youth and fair maid, minds cluttered up with all these useless anodynes for thought, quotation, imbecile epithets! Dead silent: unable to talk: from too good breakfast to probably extremely bad lunch. The young woman, so the young man is duly warned, to prepare it: pink india-rubber, half-cooked cold beef, no doubt: tepid potatoes, water in the bottom of willow-pattern dish. (No! Not genuine willow-pattern, of course, Mr Tietjens.) Overgrown lettuce with wood-vinegar to make the mouth scream with pain; pickles, also preserved in wood-vinegar; two bottles of public-house beer that, on opening, squirts to the wall. A glass of invalid port…for the gentleman!…and the jaws hardly able to open after the too enormous breakfast at 10.15. Midday now!

“God’s England!” Tietjens exclaimed to himself in high good humour. “Land of Hope and Glory!–F natural descending to tonic C major: chord of 6-4, suspension over dominant seventh to common chord of C major…All absolutely correct! Double basses, cellos, all violins: all wood wind: all brass. Full grand organ: all stops: special vox humana and key-bugle effect…Across the counties came the sound of bugles that his father knew…Pipe exactly right. It must be: pipe of Englishman of good birth: ditto tobacco. Attractive young woman’s back. English midday mid-summer. Best climate in the world! No day on which man may not go abroad!” Tietjens paused and aimed with his hazel stick an immense blow at a tall spike of yellow mullein with its undecided, furry, glaucous leaves and its undecided, buttony, unripe lemon-coloured flowers. The structure collapsed, gracefully, like a woman killed among crinolines!

“Now I’m a bloody murderer!” Tietjens said. “Not gory! Green-stained with vital fluid of innocent plant…And by God! Not a woman in the country who won’t let you rape her after an hour’s acquaintance!” He slew two more mulleins and a sow-thistle! A shadow, but not from the sun, a gloom, lay across the sixty acres of purple grass bloom and marguerites, white: like petticoats of lace over the grass!

“By God,” he said, “Church! State! Army! H.M. Ministry: H.M. Opposition: H.M. City Man…All the governing class! All rotten! Thank God we’ve got a navy!…But perhaps that’s rotten too! Who knows! Britannia needs no bulwarks…Then thank God for the upright young man and the virtuous maiden in the summer fields: he Tory of the Tories as he should be: she suffragette of the militants: militant here on earth…as she should be! As she should be! In the early decades of the twentieth century however else can a woman keep clean and wholesome! Ranting from platforms, splendid for the lungs: bashing in policemen’s helmets…No! It’s I do that: my part, I think, miss!…Carrying heavy banners in twenty-mile processions through streets of Sodom. All splendid! I bet she’s virtuous. But you can tell it in the eye. Nice eyes! Attractive back. Virginal cockiness…Yes, better occupation for mothers or empire than attending on lewd husbands year in year out till you’re as hysterical as a female cat on heat…You could see it in her: that woman: you can see it in most of ’em! Thank God then for the Tory, upright young married man and the suffragette kid…Backbone of England!…”

He killed another flower.

( – from Some Do Not…, Part One, Chapter 6)

Pardon me for quoting that again but it is one of my favorite parts of the work. I guess after spending a month and a half with Parade’s End it is worth looking back at some of the high (and low) points. I feel I should say something insightful about the books, but frankly I’m too drained (in a good way) to even attempt it. So what follows are some very random thoughts…

I found it difficult to start each volume except for A Man Could Stand Up. I’m not sure why, but it took me a chapter or two to “get into” them. I look back at the start of Some Do Not… and I don’t understand the hesitation other than being slowly immersed into what is happening. Even when totally engrossed in the book I could rarely read more than 20 pages a day. Some of the slowness had to do with taking notes, but the main culprit was trying to untangle everything layered in the work. As Ford moves toward recording only the consciousness of his characters, I read slower to try and catch as much as possible. I say this not to discourage anyone from reading it but instead to help in setting any expectations in approaching the books.

By Part Two of A Man Could Stand Up I was reading slowly just to savor Ford’s language in describing what was happening around Tietjens in the trenches. Everything had led up to these moments and I completely fell in love with the work. Some will…while some will not. You can summarize the plotline easily but it will not convey the power from his design in telling it. What actually happens in the books is revealed almost incidentally as the consciousness of the characters mull over the history and context of what is happening in order to bring meaning to the action. Ford’s process makes the nature of understanding and perception a central focus of the books.

In looking at Christopher Tietjens, we see an austere brand of ancient Englishness, passive but dignified. Despite holding him up for ridicule, Ford has him succeed in impossible, changing times. Tietjens succeeds because he embraces the English countryside whose features are “pleasant and green and comely. It would breed true.” The land, having threatened to engulf him and his regiment during the war, remains the one true force that has survived and will continue to do so. Throughout the books, Ford criticizes both pre- and post-war conditions in England, some of which is personified in the Tietjens irony. Christopher seeks a foundation in the past while overlooking the full effect of it, such as the confiscation of the Groby estate from a Catholic family. The pastoral vision at the end stands at odds with the reliance on the industrialized Americans supporting it (not to mention the coal fields owned around Groby).

Despite the defeats meted out to Tietjens, he survives the social and political breakdowns by turning his back on the established order and embracing a pastoral life (albeit a dark one, as alluded to in the inherent contradictions above). Ford seems deeply ambivalent about the lost society as well as the new order. Tietjens, a throwback to an era that didn’t exist as remembered, upholds many of the virtues that were supposed to provide society’s foundation. In one sense, Ford tiptoes around the problem of wishing for traditional values which were unable to deal with modern problems by pointing out that the underlying virtues were only observed in their breach. By assigning a false nostalgia he lightens the contradictions a little. Ford proves to be extremely adroit when presenting contradictions which makes it difficult to ascribe exactly what he is doing. Multiple readings, or at least varied interpretations, are possible. It’s also possible he didn’t even know what he was ultimately trying to say, which may be the most satisfying answer of all for me.

Below are the posts I made involving Parade’s End as well as links to the blogs of those reading along on the work:

Parade’s End

Some Do Not… discussion: Part One

Some Do Not… discussion: Part Two

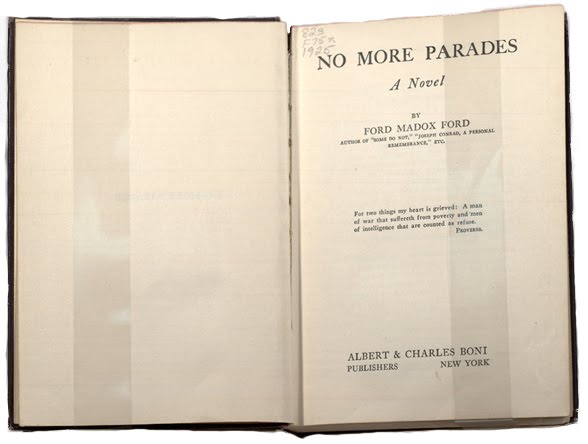

No More Parades discussion

No More Parades discussion: random notes

A Man Could Stand Up discussion

The Last Post discussion

Odds and ends on The Last Post and Parade’s End

Related posts

Online resources (updated yet again)

World War I color photos

An excerpt from and link to Ford Madox Ford’s poem Antwerp

A look at some poems by George Herbert that appear in Parade’s End

So what is Christopher’s son’s name?

Some random notes on the BBC adaptation of the novels

Also participating in the read-along

Mel U at The Reading Life

Hannah at Hannah Stoneham’s Book Blog

Nicole at bibliographing